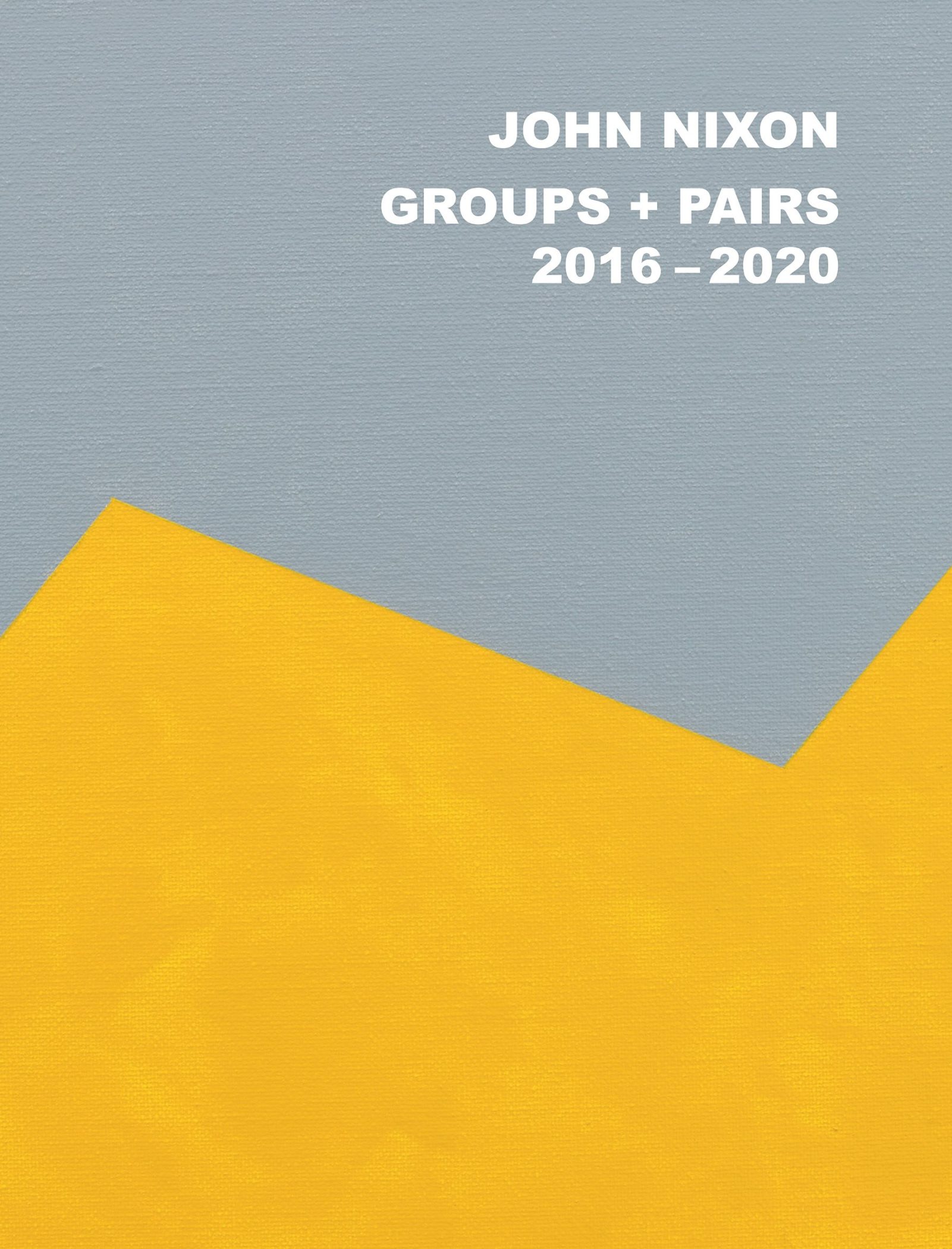

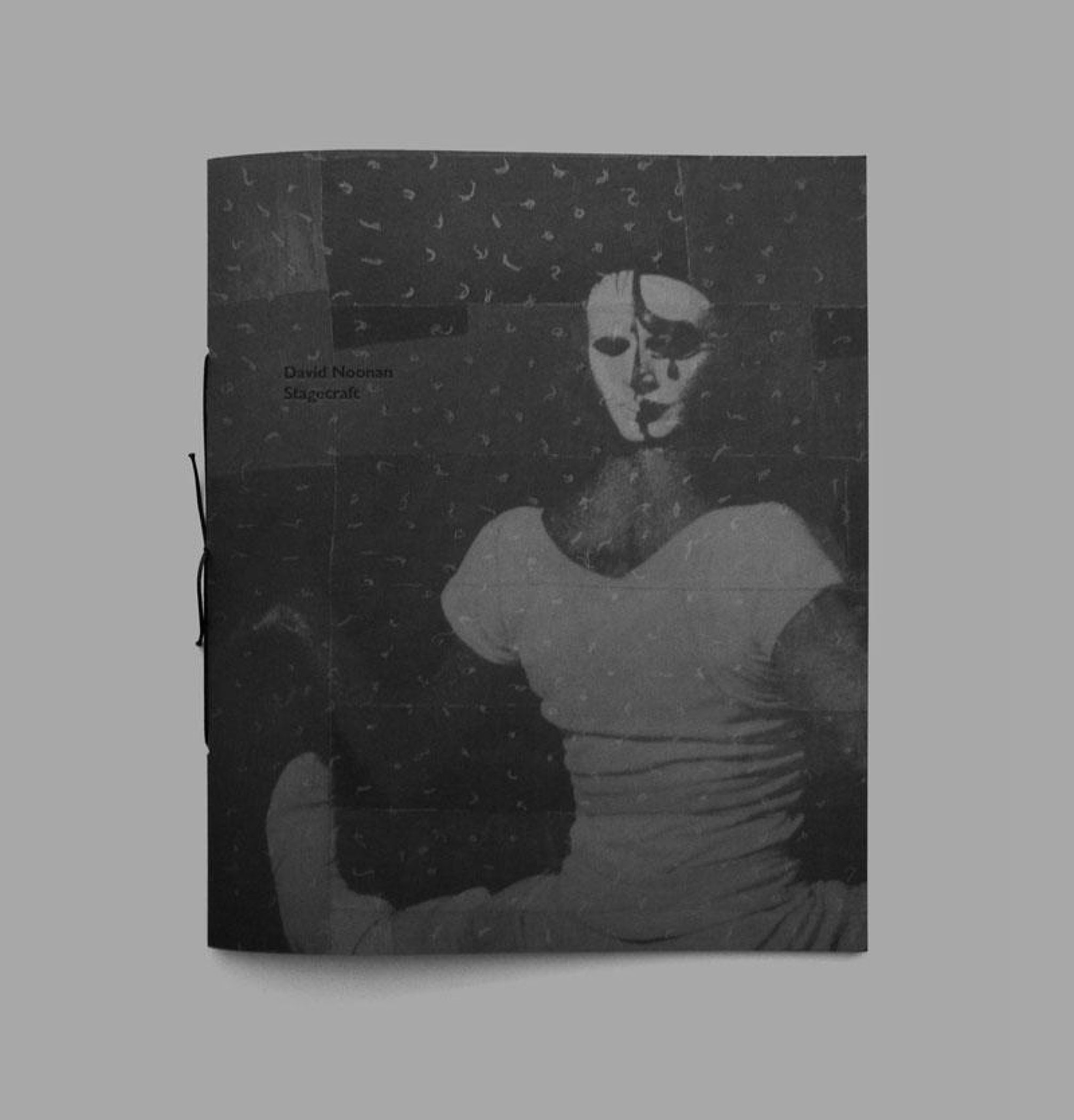

David Noonan: Stagecraft

In in-depth discussion with David Noonan while the exhibition is in hibernation.

You were born (and studied) in Ballarat, yet this is your first solo exhibition in the city (I believe, please correct me if I am mistaken). How did this exhibition come about, and what has the process of preparing to exhibit your work in the city of your birth been like for you?

It’s not strictly my first solo exhibition. I curated my own exhibition in my apartment in the 1980s — probably around 1987. My apartment was on Sturt St, a recognisable building that was built in 1865 (next to the old Thomas Jewellers shop). The exhibition was called Industry and Arcadia and featured paintings from my second year of art school at Ballarat University College. All I’ll say is, at the time, I was very influenced by 1980s Neo-expressionism and the New Romantic movement.

I was invited to show my work at the Art Gallery of Ballarat by Julie McLaren in 2018 and was delighted at the prospect of exhibiting in my home town. In terms of the process, the initial logistics were complex due to the fact that I’ve lived in London for over 15 years and my work is in many places. The show is not a major retrospective nor is it a conventional survey show, because these usually cover a longer period of time. It’s rather a mini survey of my work over a shorter period, and it is work that has never been seen together. I decided to use recent work from a show I did at Xavier Hufkens in 2005 in Brussels, as it represented the palette I want. I’m also using work from a recent show at Anna Schwartz Gallery (2019), and a recent film (2017−2018). The idea was to create a show of recent work that had strong, yet materially different, qualities. I see it as more of a concept exhibition than a survey.

The show is a homecoming in the sense that it is an honour to be acknowledged and recognised in my home city. But, much of my family still lives there, so I do have strong ongoing connection to Ballarat, as I visit at least once a year. I still have a strong association with Ballarat’s history, architecture and its overall sensibility — the town always had a melancholy feel to me and that has definitely influenced my aesthetic in both art and music.

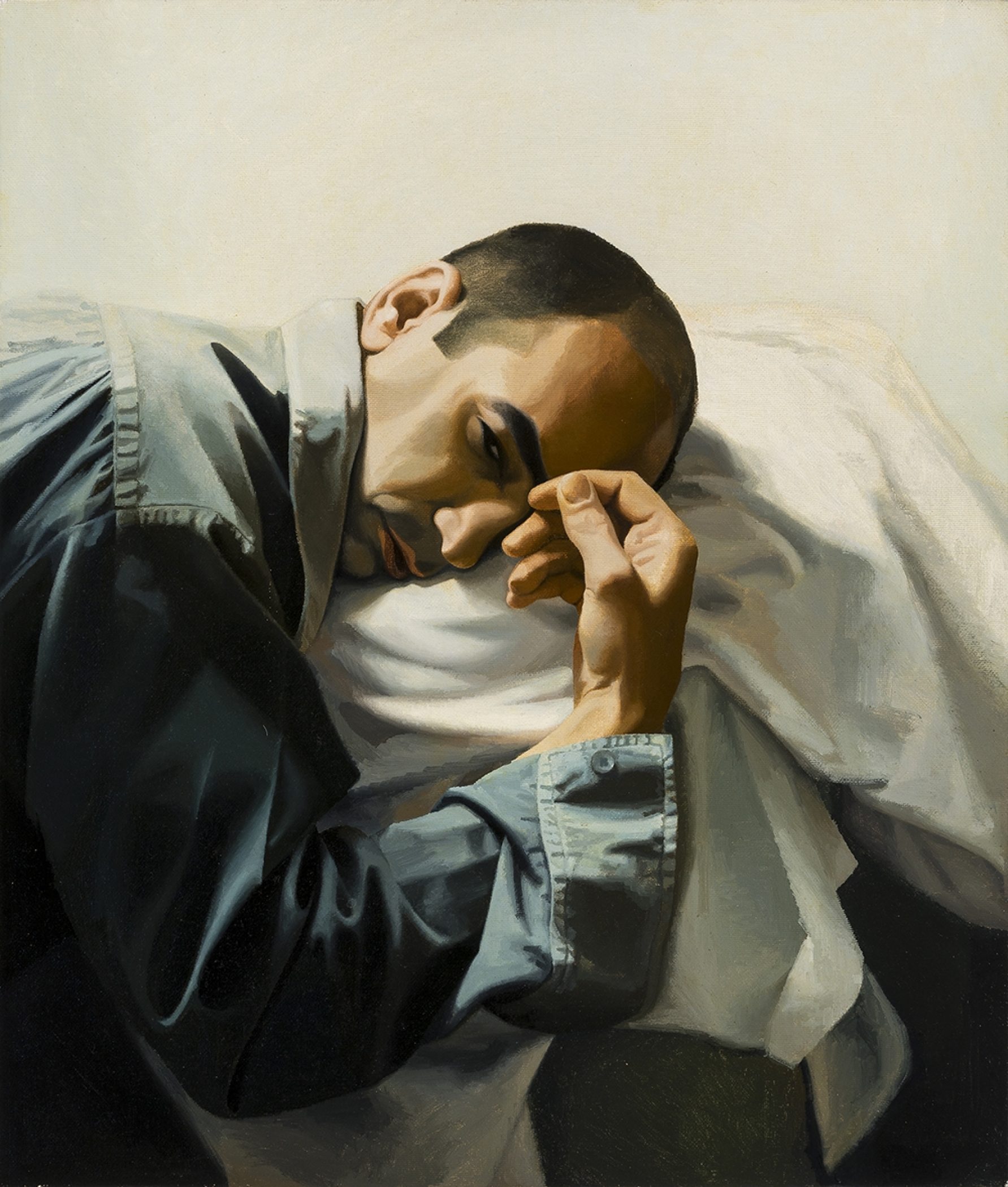

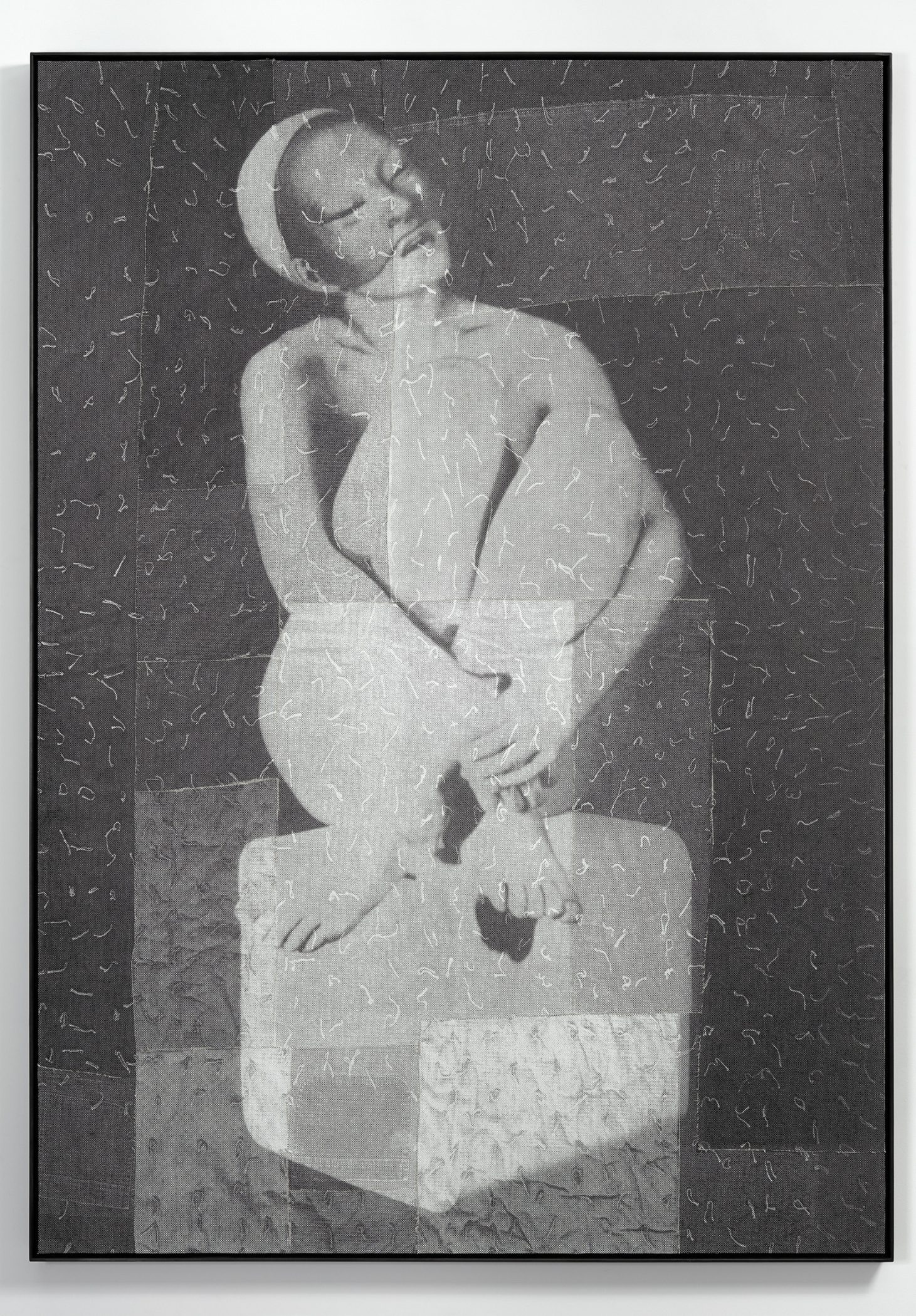

David Noonan

Untitled, 2019

Jacquard tapestry

195 x 135 cm

To stay with place, you currently live and work in London, and much of your work, in my viewing at least, explores the theatre scene. When did you make the move to London, and how important has a London locale been to your practice?

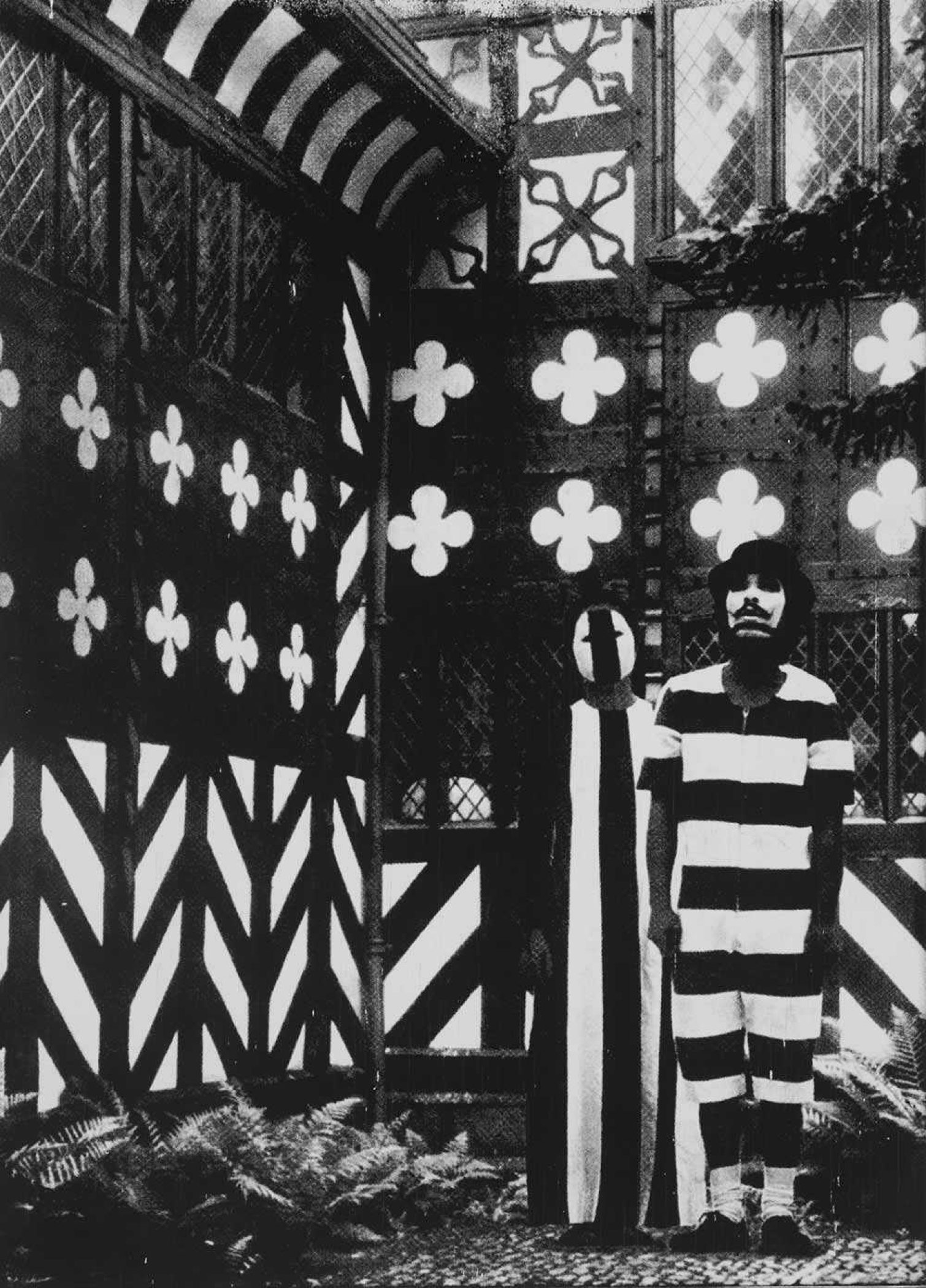

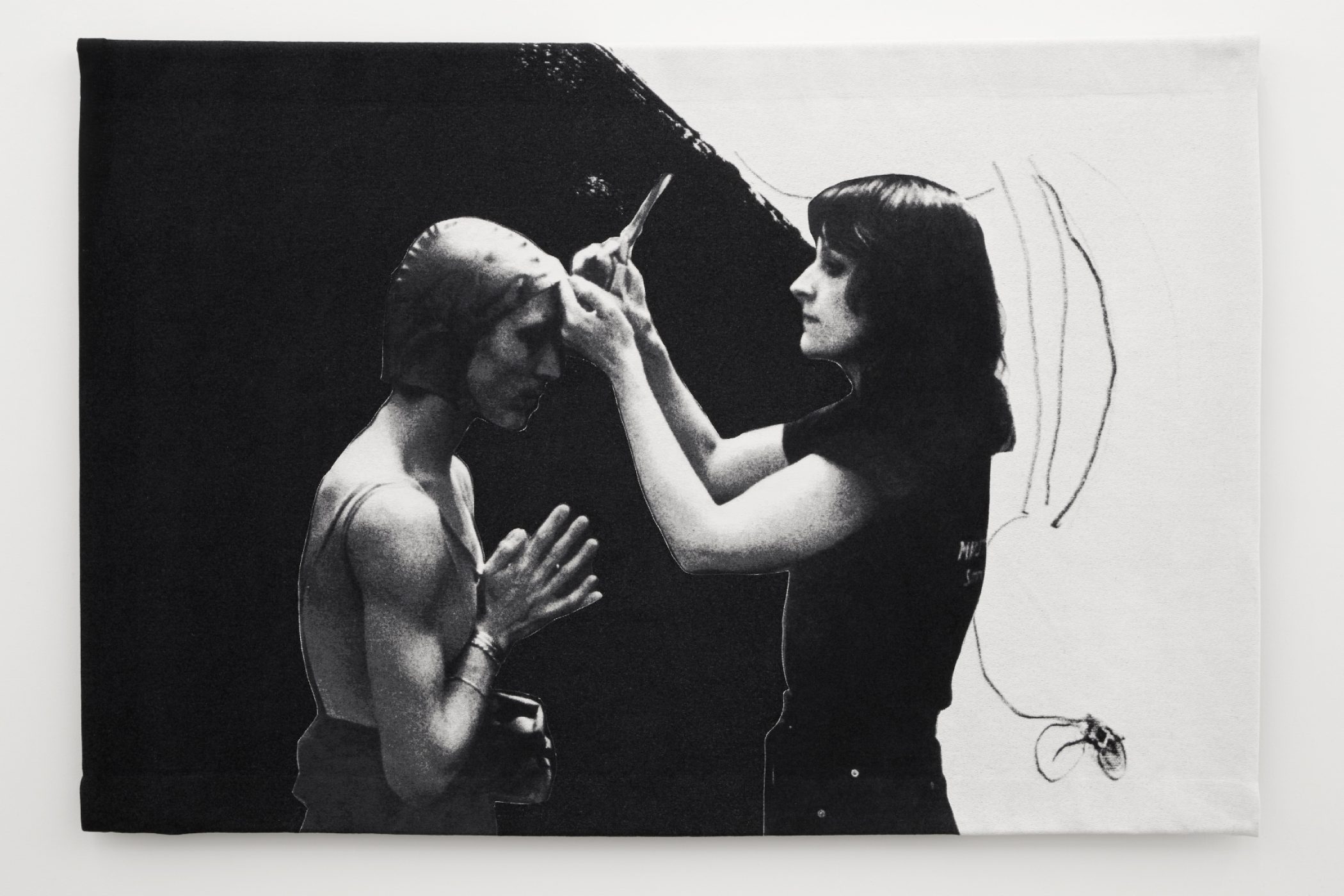

It’s not so much the theatre scene, but more a theatrical aesthetic from particular moments in time. I am interested in gesture and more broadly in the phenomena of self-transformation, which is why people wearing or applying makeup feature a lot in my work. I think growing up in Ballarat has something to do with this. My friends and I did not ‘fit in’ to the status quo, so we were almost forced to create our own realities that differed from the ones we found ourselves in. We invented worlds which often included dressing up or creating elaborate fictional scenarios.

This has undoubtedly found its way into my work. I am interested in the idea of transgression and transformation, and aspects of mystery which is often associated with subcultures. As a teenager, I was fascinated by cultural movements such as punk and new wave and also in performers such as The Sex Pistols, The Damned, David Bowie, Lou Reed, Siouxsie Sioux, The Slits, Steve Strange, Adam and the Ants, et al., all of who questioned traditional notions of gender and sexuality. For me, L’espresso – a record/café/video store – was the cultural hub of Ballarat at that time, and it still is after 40 years. It was a major influence and the owner Greg Wood, who employed me when I was 17, essentially gave me an education in art, music and cultural in general — we are still friends after all this time.

I initially moved to London in 1995 on a two-year visa. I moved back to London in 2005 after living in New York City and doing various residencies. I started working with Foxy Production in New York City, then I was picked up by David Kordansky in Los Angeles, and through that exposure I was provided with the new phenomena of international art fairs. I was signed to a gallery in London, and that inspired my move back here, not to mention my wife Renee So had a London residency for three months which made the transition easier.

Moving to London gave me easier access to Europe and USA, and provided me with many more opportunities. It was an interesting time to be in London as the art world was changing in an exciting way with new younger galleries opening and a shift in part to the east end. There was an energy there that had not been present since the late 1990s.

David Noonan

Untitled, 2019

Jacquard tapestry

195 x 290 cm

How did you arrive at the title for this exhibition (‘Stagecraft’)? In your view, what does this title say about your practice, and the works of this exhibition specifically?

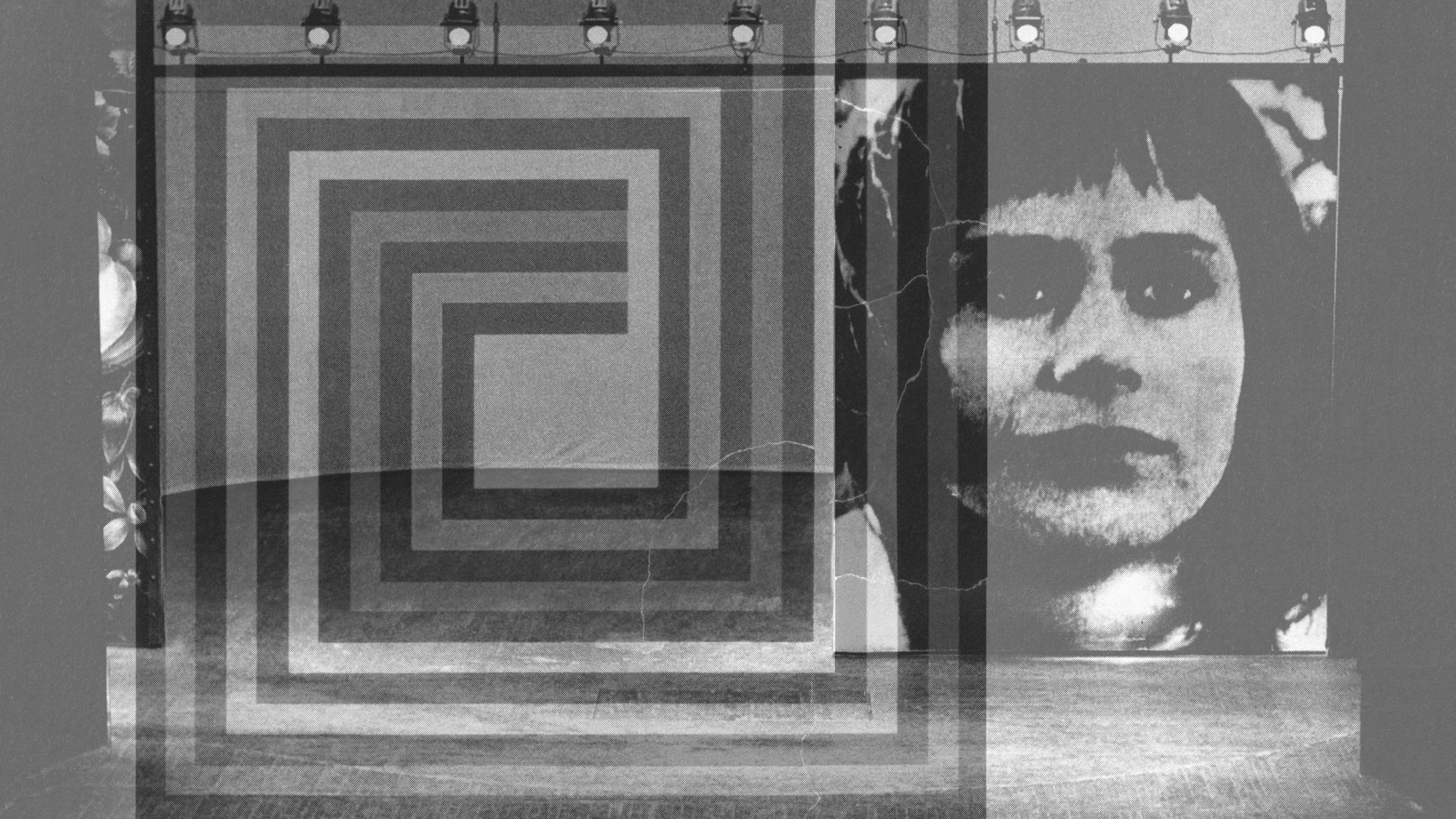

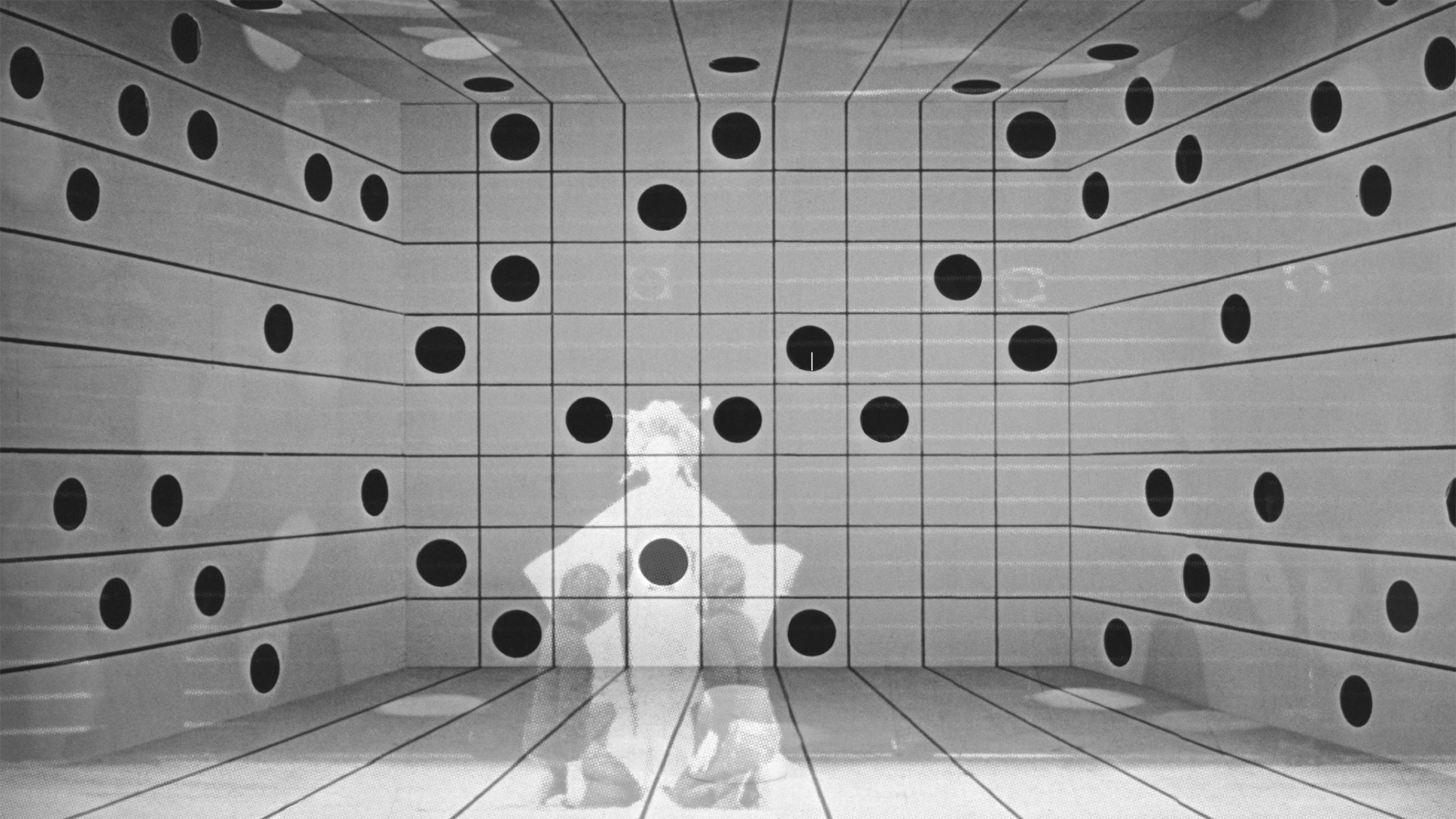

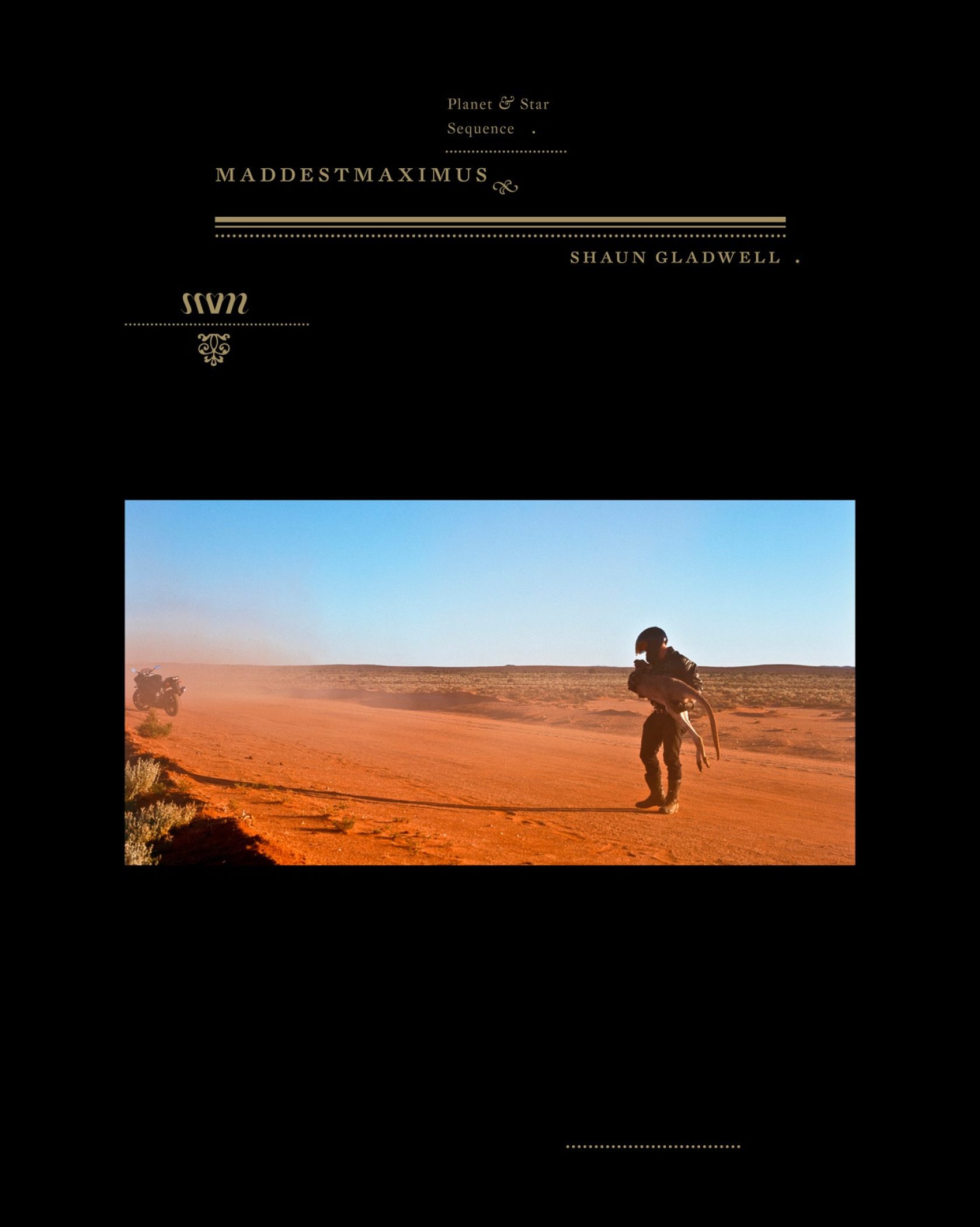

The thing is, I rarely actually see theatre, I am more interested in the concept and history of theatre. I love the inventiveness of creating other worlds. It is like science fiction in some ways, but it has a limited parameter, which is determined by the stage. These were my initial thoughts in relation to the title. There are so many possibilities that can be articulated through costume, acting, architecture, props, etc, and it’s essentially pretending — it is an interpretation of the world in a distilled context. This is most explicitly expressed in the film that I will be showing: A dark and quiet place (2017 – 2018).

I had considered the title ‘mise en scene’, but it was a bit too pretentious for me. I started thinking about the construction of theatre, which is really stagecraft – that’s what it is called, the effective management of theatrical devices or techniques. This also relates to my process as an artist, how an artist creates an exhibition — that too is stagecraft — because it is a sense of transforming and manipulating an existing space for a very particular effect. As my work is so much about atmosphere and materially sensitive environments, it becomes as much about art direction as everything else. It is about creating a very particular environment in which to experience the works on display, even if those decisions often remain unnoticed by the viewer.

This exhibition brings together works of yours created between 2015 and 2020. How many works will be on show in total? Do you see “2015 – 2020” as a means of structuring the exhibition in any way, or is it simply that it took five years to complete the works that would make up ‘Stagecraft’? In other words, what is the significance of this time period?

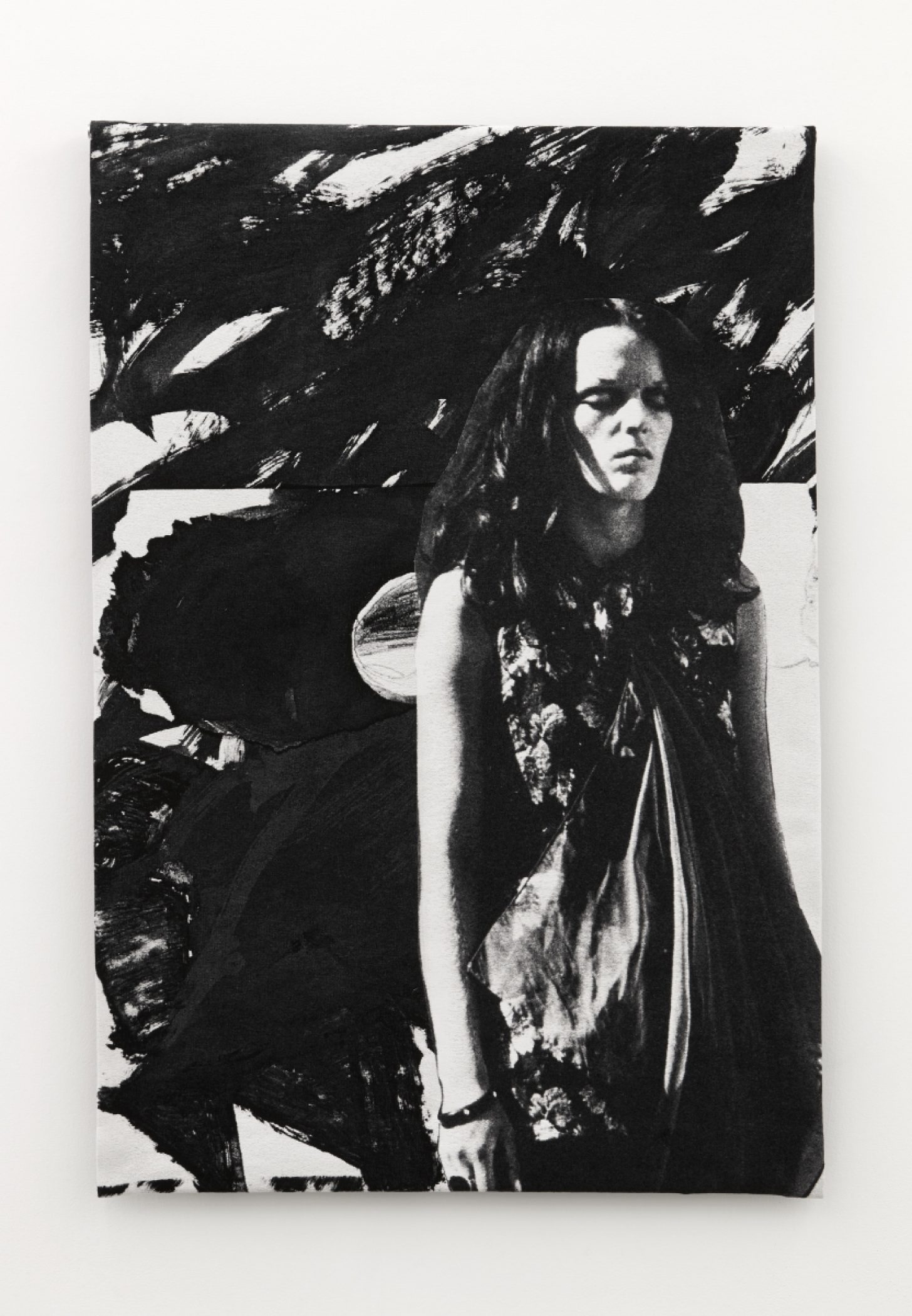

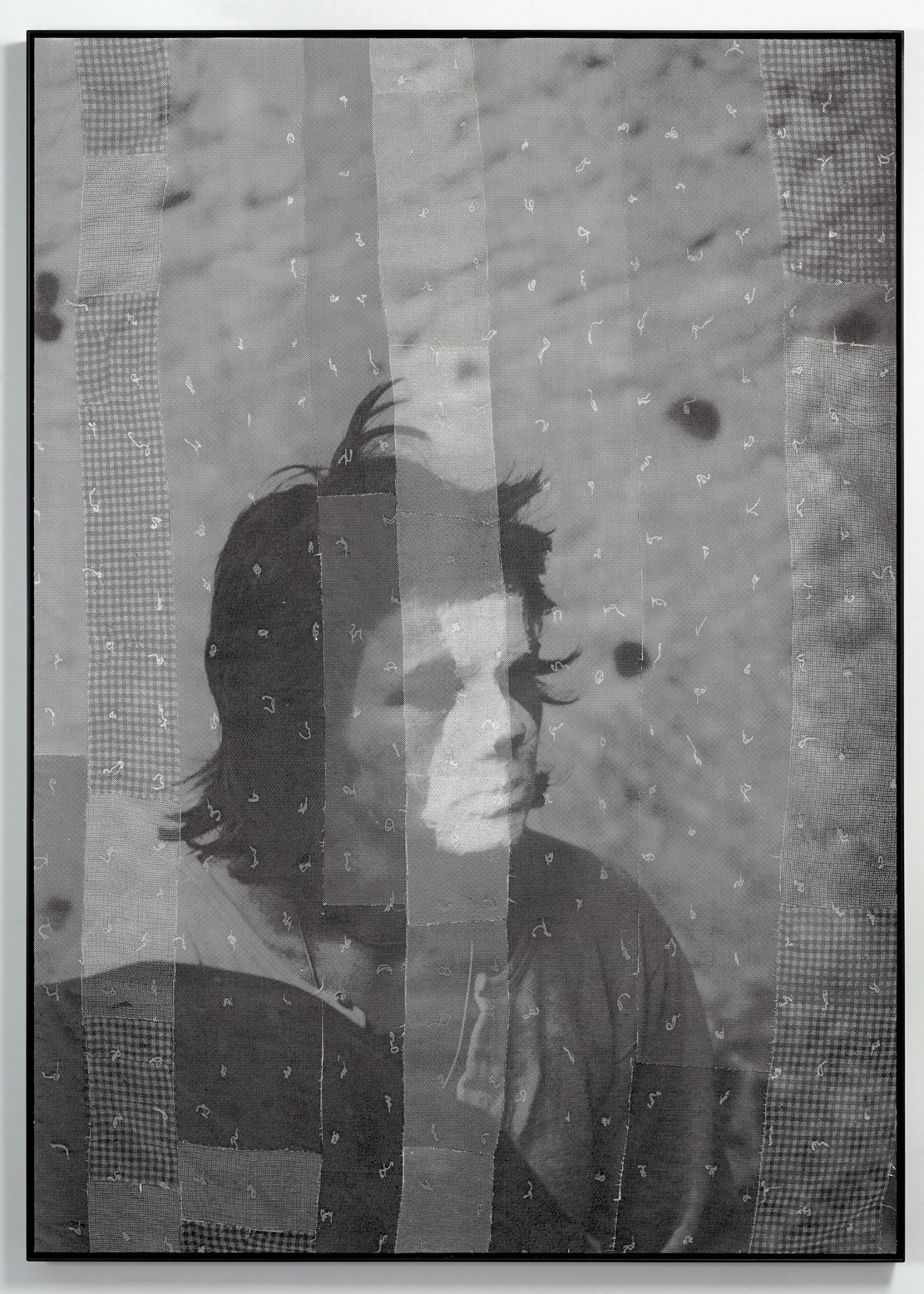

There are twelve works in total, and a publication with a limited edition print. The underlying concept of this body of work from 2015 – 2020 is the palette and the diverse material realisation of that particular tonal range. Directly responding to the exhibition space, I conceived of using the three discrete rooms to represent three aspects of my practice during this period: my better-known silkscreen on linen collages, my recent tapestries, and a recent film. Each of these approaches, respectively, have a different material element, but they are tied together insofar as I used found imagery to create all of them, and they are all black and white (whereas before this period my collages had a sepia quality because they were printed on raw linen). The purely greyscale palette is a distilled aesthetic that serves to create a tonal continuity between the works.

This exhibition “brings together silkscreen collages on fabric, tapestries and film”, why did you decide to exhibit more than one medium here? What is the relationship between these different forms? What is the process from found imagery to completed work, and how does this change across media? For example, how do different textures and techniques impact on the creation and meaning of your works?

There are different types of collage and different ways of collaging. The silkscreen collages require a complex silkscreening process undertaken in a specific printing studio, and are then assembled by hand in my own studio. With the tapestries, the Jacquard loom assembles the works into dense mise-en-scène and translates the flattened imagery into a tactile, sculptural woven medium. In the process, the initial composition, which was made from handmade paper collages, is transformed and the materiality of the tapestries is brought to the fore. In my film, I drew from my archive in a very particular way. The film’s formal qualities are organised by selecting and piecing together both figurative and abstract imagery to create a conversation between them. The film is created entirely from still images, not filmed footage, and collage techniques are reinterpreted as filmic montage. The relationship between these different forms is that collage is realised in three different mediums using three different processes.

What is the significance of ‘craft’ to your practice? The exhibition description mentions your collaboration with Belgian weavers and how this facilitated the use of traditional craft techniques. And, of course, the nature of collage means that your works are ‘crafted’ in a more obvious way. Plus, your works explore subjects — i.e., the performance arts and of ‘the stage’ — that are often defined as a ‘craft’. So, what does craft mean to you? And what are the various articulations of it that are on show in this exhibition? Can you illustrate via an example from the exhibition?

I have a problematic relationship with the word ‘craft’. Isn’t all artistic practice ‘craft’, in terms of the ways in which artists assemble their work in general? It is such a complex question and a complex term. Historically, ‘craft’ was viewed as a utility. And even after Anni Albers pioneered the term ‘textile artist’ in the 1940s, ‘craft’ was used as a gendered, pejorative term. It is a term that has been rehabilitated today, but it still raises questions about what is considered valuable, and why, in the art world.

How do you go about selecting the raw materials for your collages? In other words, what is your process of selection? And why do you work in black and white?

It is a difficult question because I amass material that appeals to me. Rather than trying to place too much emphasis on systematically ‘putting things together’, my practice is more reliant on serendipity and coincidences in time. It is not so much a process of selection, but rather one of alchemy. As an example, I may have had an image in the studio for many years, lying dormant, and then I finally find another image that activates the one that has been lying around and something quite special happens – a piece may come out of that.

Of course, it’s not only alchemy, but availability. Nowadays it is increasingly difficult to find material, as bookshops are closing down. As my process changes it reflects wider changes in society.

The exhibition description says, “Documentary images are transformed into fiction, suggesting the significance of theatricality and performance in the public realm.” Can you elaborate on this? What is the role of truth in your work? And how exactly do you ‘transform’ through your art? Can you give me an example based on the creation of one work from the exhibition?

Truth does not fulfil a role in my work. I prefer an approach that is much more ambiguous and that leaves interpretation open to the viewer. I don’t like the idea that you have a specific agenda that has to be unpacked to understand it. I prefer the notion of evocation and suggestion, rather than anything empirical.

My favourite artworks are like songs — they affect you — but you don’t need to understand exactly why. You can be left with a feeling that operates on an emotional level or in terms of the senses and that I hope can be a meaningful encounter for the viewer. I hope my art also has a sensibility or ambience that somehow remains mysterious. But, often achieving this result involves a very difficult, rigorous process. It needs to strike the right cord with me for it to be successful as art.

Also from the exhibition description: “Noonan repurposes found photographic images from his extensive personal image archive to create images which are ambiguous, often with a focus on a solitary haunting figure.” Can you elaborate on this solitary figure? What makes you select this figure? How does this figure emerge through your work, how is this figure constructed in your artistic process and what meaning, if any, do you intend those viewing your work to draw from this ‘crafted’ figure?

I see the solitary figures in a number of ways. The first thing to note is that there is not one so-called ‘solitary haunting figure’, there are many throughout my work and not all of them are haunting. I find it interesting that my work is often described in terms of the gothic or the nostalgic as they can be all of these things and more — open to broader interpretation. Often the solitary figure in my work is one involved in an introverted activity, such as applying makeup or being in some kind of liminal or in-between space, or involved in a potentially transitional moment.

The figures I use are representative, more broadly, of the tradition of figuration in art. There is such a dichotomy between the figurative and the abstract, that I want to question. I am interested in locating them in dialogue and I don’t subscribe to a hierachy. There is a tendency to privilege figurative works because they are easier to understand, but I think that one informs the other, that one cannot exist without the other. I’m interested in the history of art and how these different forms are valued or completely discarded and why. Trawling through second-hand book shop bins it is amazing to see how much incredible art enterprise has been metaphorically thrown on to the scrap heap of history. I look through it all and try to re-inscribe, at least some of it, with a value that is determined by my particular purpose.