Creative Cosmos: Marco Fusinato in conversation with Melissa Keys

MK: As an artist and musician, you have relationships with audiences. What drives you to make work, and who do you make it for?

MF: Well, it always begins with something I want to experience. It may connect with someone down the line … but it may not. I’m aware that the references are pretty oblique, but I find they act as a filter … they eliminate an audience I wouldn’t hang out with. There’s an expectation to make work so that it’s liked, so that it gets discussed or reviewed positively and is deemed ‘successful’ if it sells … I find this abhorrent. I know from the outset that my interests and audiences are marginal, ugly and unpopular. There’s no expectation so I’m never disappointed. For example, when I do performances of solo-guitar-noise the audiences are very small and specific. In any big city around the world there are generally the same looking 50 people at the shows. However, if I’m performing as part of something bigger, a festival for example, I may start off with 200 people in the room, but during the performance most can’t handle it, they don’t understand the language, don’t know the references, don’t get it, don’t like it and therefore they leave … so in the end, it’s the same 50 weirdos left in the room. That’s who I make work for.

Marco Fusinato

THERE IS NO AUTHORITY, 2012

100% New Zealand wool rug, monitor, camera

9.25 x 12.04 metres

Installation view, Anna Schwartz Gallery, Carriageworks

Marco Fusinato

THERE IS NO AUTHORITY, 2012

100% New Zealand wool rug, monitor, camera

9.25 x 12.04 metres

Installation view, Anna Schwartz Gallery, Carriageworks

MK: Your work features images of social agitation and political crisis and at the same time suggests utopian possibility. I’m interested to hear you reflect on how your practice corresponds with history.

MF: I’m continually not only cross-referencing what I’ve done in the past but also re-examining early influences. There’s a lot of research and contemplation involved; however, the reality is I spend a lot of time working out practical solutions to unorthodox manufacturing and presentation problems. How do I suspend that alloy tubing … do I need shackles and master links … how many? Should I swap out the Mullard EL34s? How thick should the lip on the frame be, 19 mm or 24 mm? What DPI is that image? How strong is VHB tape really? Mastering at ‑6 dB. Trilobal polyester. Casting in bronze. Downtuning to brown standard and dropped brown. Martin Atomic 3000 LED. Meyer Leo or Leopard? Angle grinding into brass. EGC #569/black and #654/polished. Subs at 15 Hz. 3D printing with air. Pressed flowers.

The American minimalist composer La Monte Young talks about one of his strongest influences being the wind that blew through the chinks in the log cabin in Idaho that he was born in and the particular impression the tonality of that sound made on him as a child. That got me thinking about my childhood memories of sound. I grew up in the working-class suburb of Noble Park (south-east of Melbourne), and I would wake up in the morning to the sounds of Simsmetal at the end of the street crushing cars and scrap metal. There’s a particular reverberation that occurs at 7 am on a still morning. It’s really beautiful.f

Marco Fusinato

THIS IS NOT MY WORLD, 2019

Installation view, Anna Schwartz Gallery

Photo: Andrew Curtis

MK: Your work takes various forms, including installation, performance, photographic reproduction and recording. Have the interrelationships between these forms changed and evolved over time?

MF: Things are always mutating and changing. It depends on what’s on offer and when. Exhibitions are usually years in the making, while a performance might be programmed only a couple of months in advance. There’s a big difference in the dynamism. With exhibitions, there’s not much immediate response; it trickles down over time, perhaps years. With a performance, you have a sense of its reception immediately.

MK: Do you prefer the immediacy of performance? Does the connection feel closer with audiences for music and sound who share this language?

MF: Exhibitions and performances are very different experiences, each with their own factions and subgenres. The audiences for a grindcore gig are there because they’re into grindcore, so immediately there’s a closer connection. The audiences at an exhibition are there for a multitude of reasons, some of which may have nothing to do with the work on display.

MK: Your research and interests encompass a wide array of intellectual traditions, social and political movements and forms of culture. What ideas, forms of making, cultural codes and languages are you engaged with at the moment?

MF: Septic Death, Faceless Burial, Blood Incantation, Vile Apparition, Infest, Discordance Axis, Internal Rot, Incinerated, Headless Death, Exclaim, Siege, Gauze. 12” LPs here in front of me.

It’s occurred to me that the particular Venetian dialect/language I speak is dying out within my lifetime. My parents and their generation were the last in the line of contadini (a form of pre-industrial agricultural farmer or peasant). Theirs was an oral tradition, passed down over centuries. They never learnt to speak English and only ever spoke in Veneto or, more precisely, Bellunese, the name of which refers to the region within the Veneto that my family is from. My parents were born in villages that are a few kilometres apart, and yet some words are pronounced slightly differently. I can pick the inflection. This language in its purest form is pretty much now only heard in aged care facilities.

MK: Has your selection for Venice made you think more about the dynamics of these regional and familial traditions and histories?

MF: Well, I’ve always had a strong connection as my extended family is there and we still own our centuries-old family home. My selection for Venice has made me appreciate the irony that I’m returning to the very same place my parents migrated from as the representative of the country they migrated to.

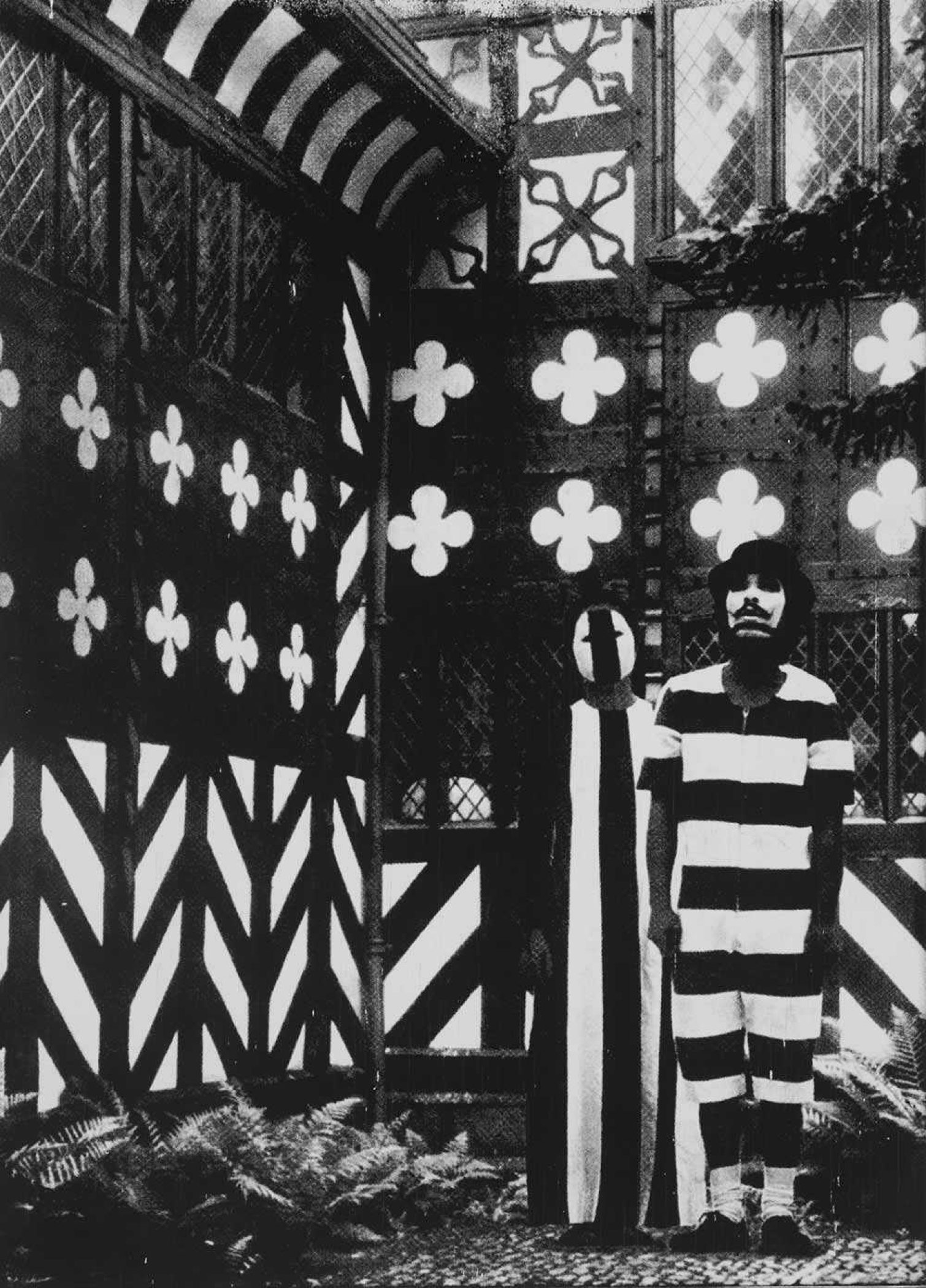

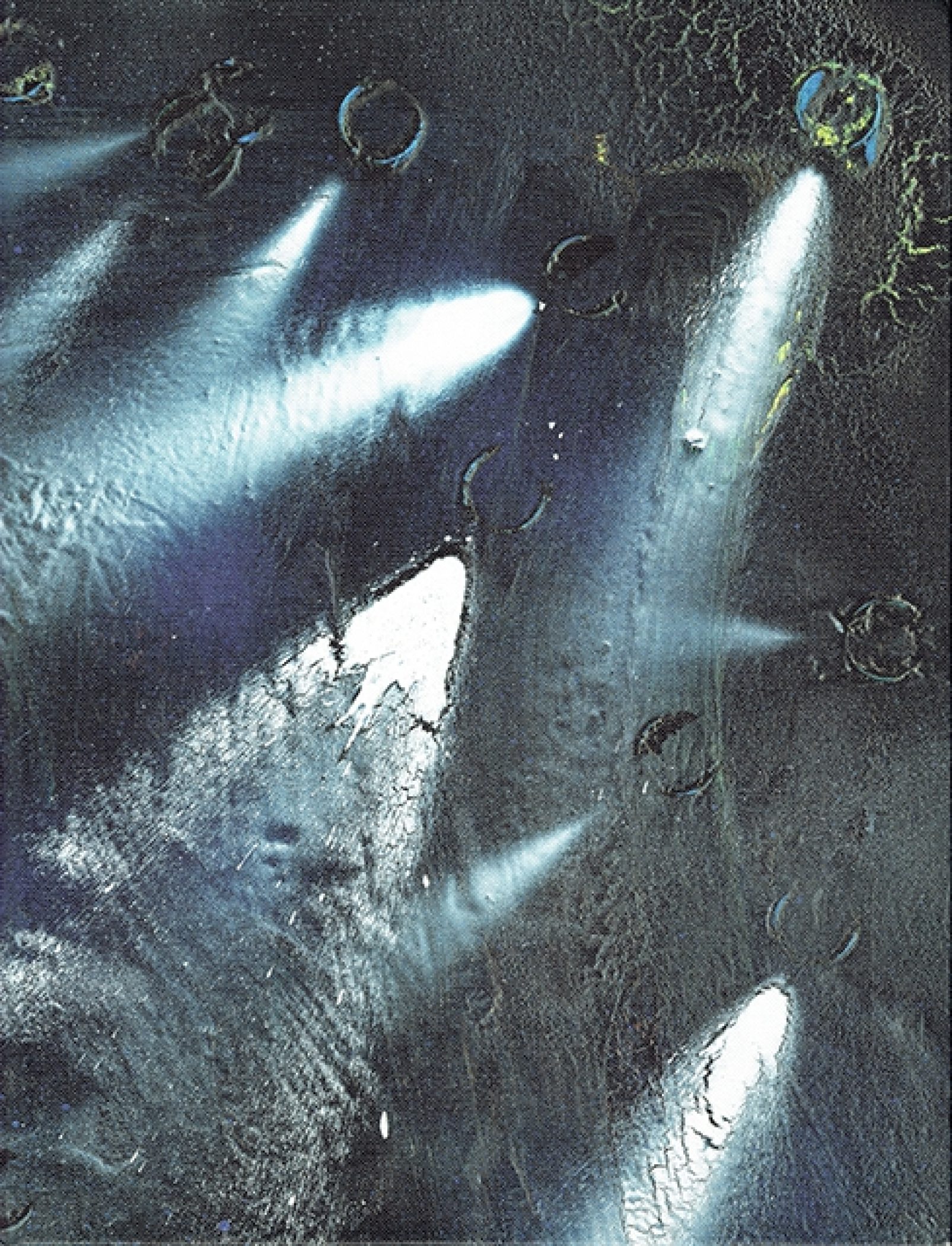

Marco Fusinato

Aetheric Plexus (Broken X), 2013

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

MK: Gestures and ideas of explosiveness, rupture, intensity and duration variously play out across your practice. Sometimes the experience of these is confrontingly visceral and other times more mediated. What interests you about the encounter with art?

MF: It’s the physicality, the experience. The fact that we have to go out of our way to get there … deciding what time to go, the weather, choosing the mode of transport, the queuing up, whatever … all of this I consider to be part of the experience; it creates a mood, a state. And once in the gallery … what happens? Are we passive or are we activated? What is our relationship to scale? Did we stay 30 seconds or did we stay for hours? The encounter with art should remind us that we have a pulse.

I’m particular about context and how that affects the reception of the work. I think the giveaway with any gallery is how the architecture of the wall meets the floor. Shadow lines or skirting boards, concrete or floorboards and so on … The gallery’s position and attitude are evident in these decisions, which determine who its audiences will be. I’m being intentionally elusive … I’m talking about details. It’s the details that can elicit intimidation, status and power.

This interview is reproduced courtesy of Buxton Contemporary at the University of Melbourne