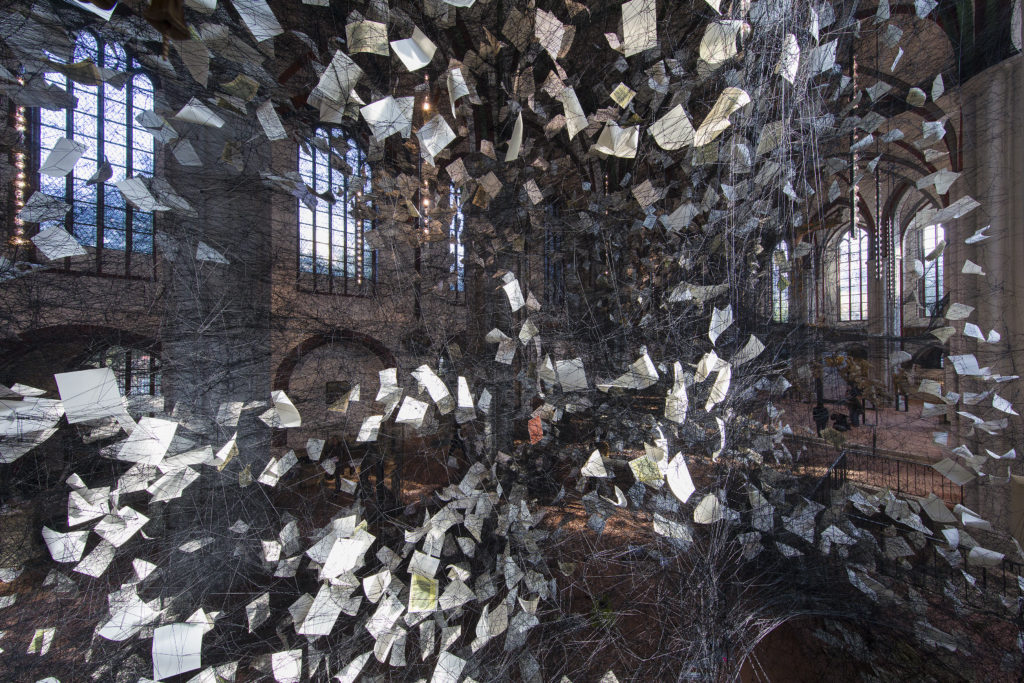

Chiharu Shiota was standing inside Berlin’s oldest church, the St. Nikolai Kirche, one late September day, putting the finishing touches on a new site-specific installation

. She had filled the church with black yarn that threaded through the space to create webbed tunnels. Thousands of sheets of paper — pulled from Bibles in

100 different languages — were tangled in the thickly woven net, as if blown in by the wind. The installation, titled

Lost Words, marks the

500th anniversary of the Protestant Reformation, celebrated across Germany on October

31. The commission also marks the beginning of a new chapter for the building — which is managed by the Stadtmuseum Berlin Foundation — as it enters its new life as a contemporary art center. Shiota, who is from Japan and has been living in Germany since

1996, was catapulted into public prominence with her grand-scale work for the Japanese Pavilion at the

2015 Venice Biennale. Titled

The Key in the Hand, the installation consisted of more than

50,

000 metal keys that were woven into a crimson web of yarn — Shiota’s signature practice — that completely covered the pavilion’s ceiling. For this edition of our

“Origin Story” series, which explores the backstories of individual works of art, Shiota takes us through the process of transforming the central nave of St. Nikolai church.

Tell me about the pages from the Bible that you’re using.

I wanted to link it to the history of Christianity in Japan. In the 16th century, Portuguese Christians came to the island as missionaries, but Christianity was banned shortly thereafter. Japanese Christians practiced their religion in hiding. You couldn’t publish the Bible or even own one, so an oral tradition of the Bible developed in Japan. I was interested in how this oral tradition made the stories themselves migrate, from person to person, but also in the meanings that shifted through retelling. The passages used here were chosen by the church, and all pertain to immigration, which is part of the concept, as I was thinking about mental immigration through storytelling.

What does religion mean to you?

I’m not religious. My parents are Buddhists. Religions are connected, and also make connections. Not specifically Christianity alone. The nets and threads represent human connections — some are intertwined with each other, and some cut off and get knotted again, going in a different direction. The black of the thread I used represents something universal, like a night sky.

And how did the invitation to do this work come about?

The Museum Nikolaikirche approached me with an invitation to do a work on the occasion of 500 years of Reformation. I came up with this idea, and they liked it.

How long does it take to create a work like this?

This took two weeks with a team of 15 people who have been working with me for a long time, and who know the weaving patterns. Usually, we have a net which we put on top just to give it the initial structure, but for this unique space, the net was not sufficient. We made everything from scratch. I cannot control everything, so I have a lot of trust in the people I work with.

Do you have a special weaving technique?

No, anyone can do it!

How did you adjust the net’s design to fit the space? How much of the original sketch ends up in the final piece?

Before creating an installation, I have to see the space and be enveloped by it. I feel as if my body and spirit transcend into a certain dimension. After this process, I draw a sketch and present my idea to the museum. But it often looks quite different in the end.

What will happen to the work after the installation comes down next month?

My work is always like this; after the show is over, it is cut and doesn’t exist physically anymore. Only in people’s memory. There are a few permanent works in museums and private collections.

“Origin Story” is a column in which we examine the backstory of an individual work of art.

Chiharu Shiota, “Lost Words,” is on view at Museum Nikolaikirche, located at Nikolaikirchplatz, 10178 Berlin, through November 19. Image credits:

CHIHARU SHIOTA,

Lost Words, 2017. Photography: Michael Setzpfandt. Article link:

here