Daniel von Sturmer

These Constructs

13th November – 20th December 2014

Anna Schwartz Gallery

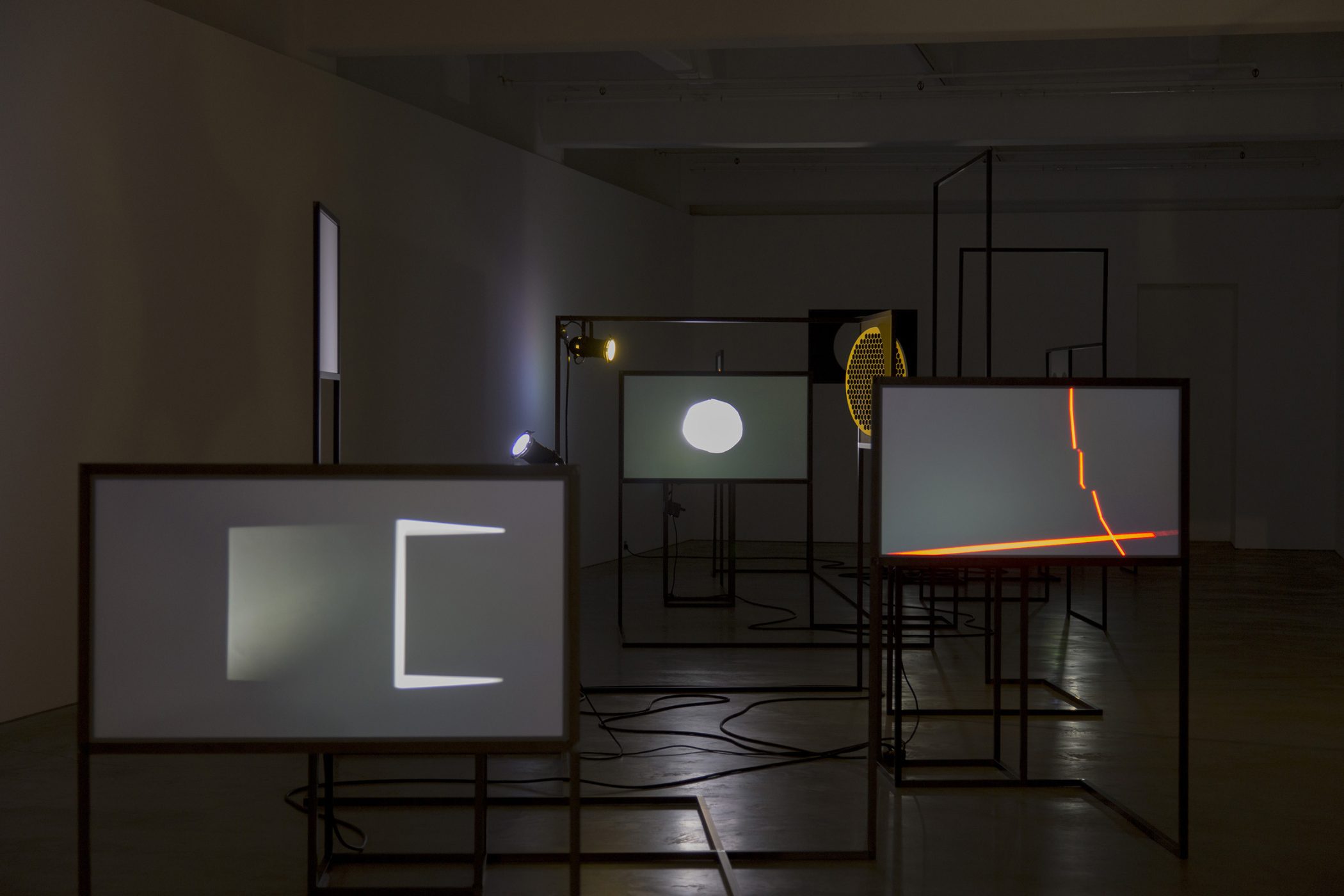

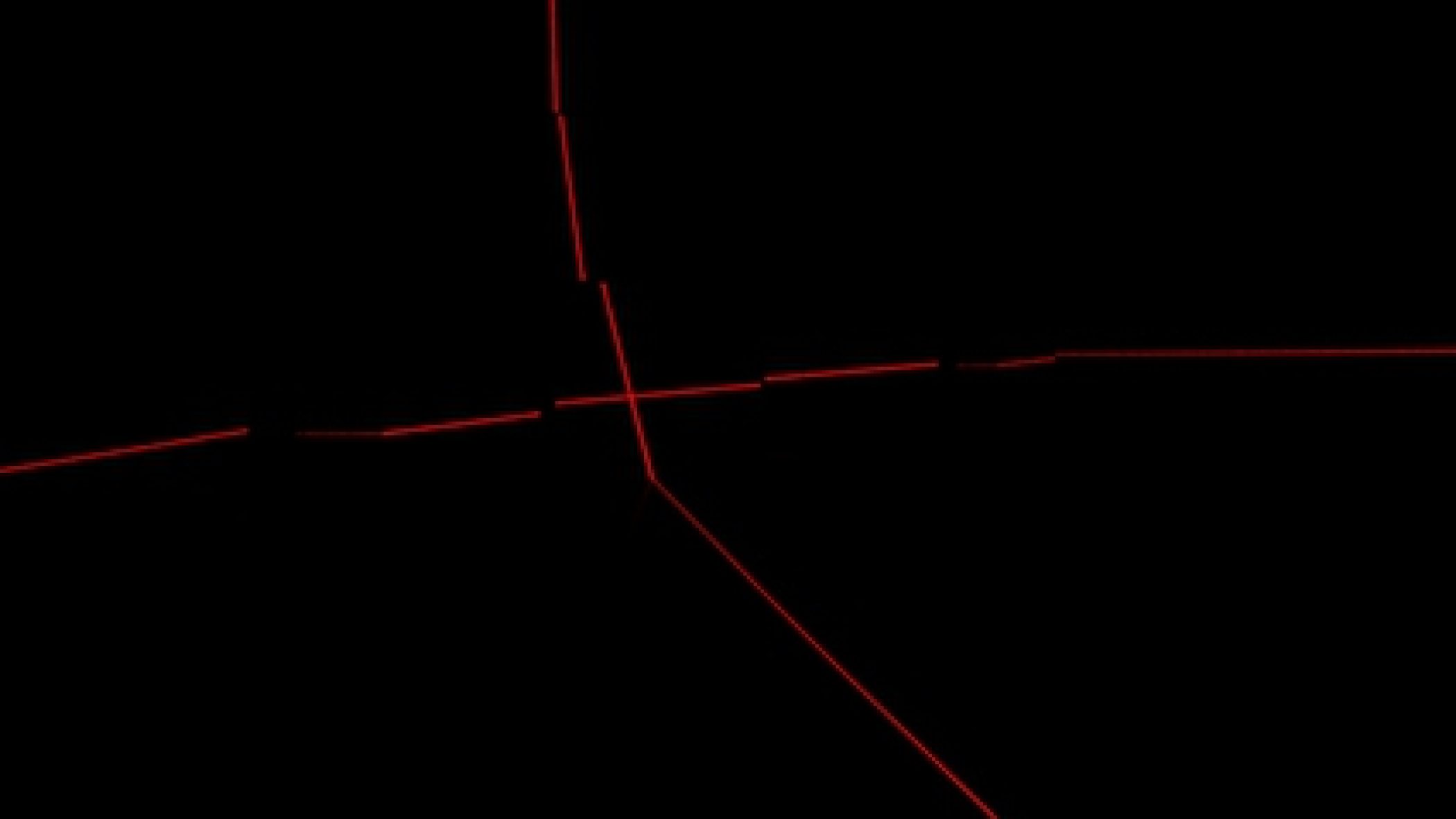

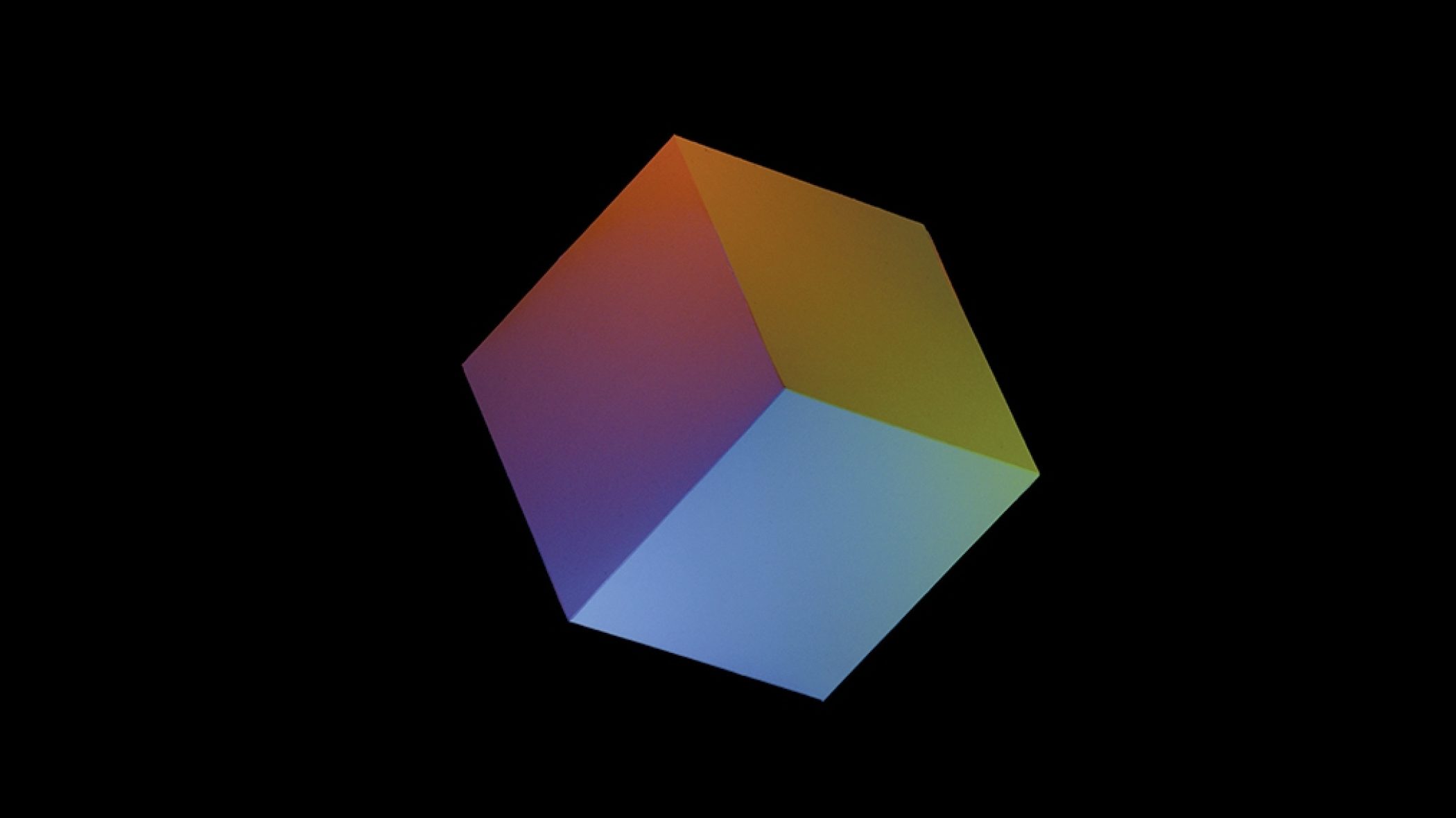

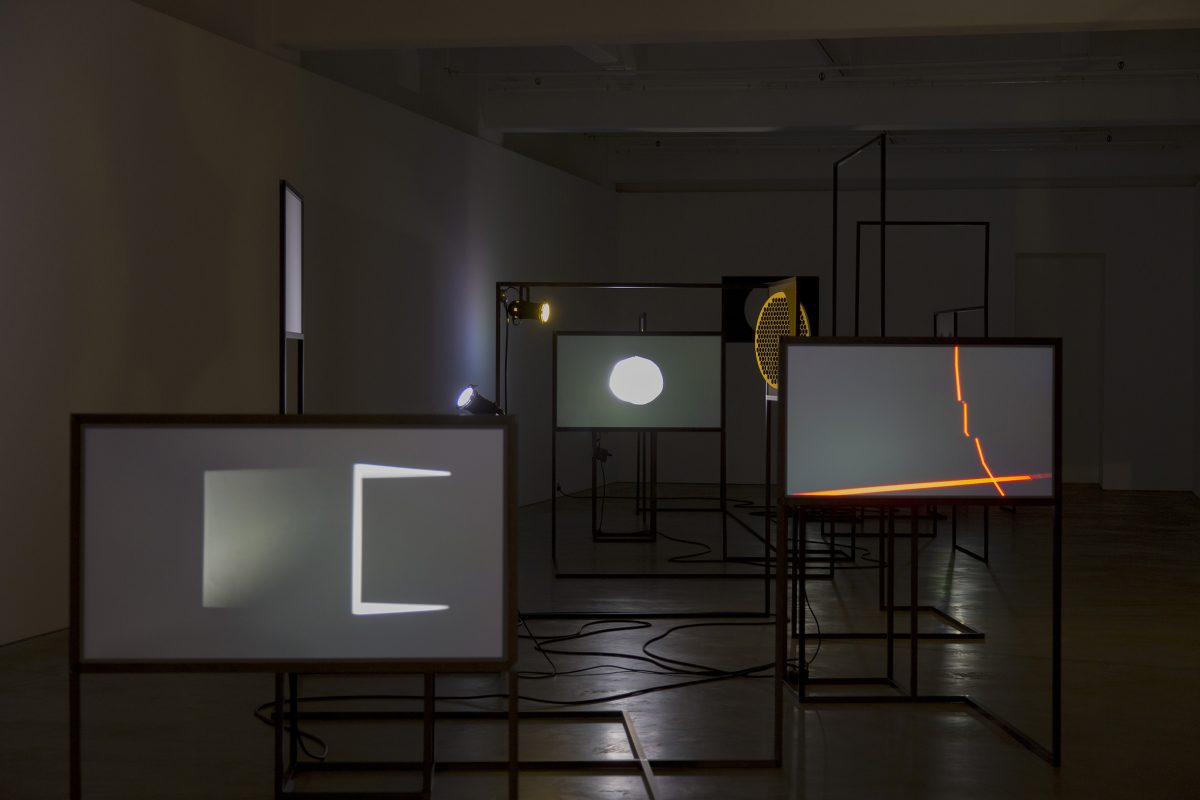

Suspended in darkness, ‘These Constructs’ is a body of work whose ostensible subject is light. Five video projections, mounted on a precisely configured rig, punctuate the dim ambience of the gallery with images of illuminated objects. A red/green/blue cube rotating in space; a white construction that appears to delineate both interior and exterior space; a hole cut into an inky black field; a pair of red lasers scanning an otherwise unilluminated composition of forms; and a torch shone from darkness directly into the camera, onto the screen. Each video shows a single, simple action, looped indefinitely. Mostly, these gestures occur as if by ‘action at a distance’, propelled into motion by invisible or non-local forces.

Spinning, slicing, raking; tense, focused and energetic motions that remind the viewer that light itself is energy: a form of electromagnetic radiation that is visible to human sight, a frequency whose wavelengths our eyes are tuned to. Each video demonstrates a different kind of light interacting with space, over time, recorded and written back into the gallery by the light of the projector. Von Sturmer has often interrogated these essential aspects of video – light, space, duration – and in this exhibition, the study is as reduced and controlled as ever.

These short loops are propositions about the nature of the video image and the space it presents. Too easily, one might accept them as virtual, computer-generated images; it is harder to believe that these are indeed studio-based, IRL (in real life) experiments, perfected. Unedited but for simple cuts and using little more than a light source (the ‘photo’ in photography) and prosaic studio materials, von Sturmer points directly at a very contemporary symptom, the discrepancy in perception between virtual and real.

Walking around the customised lighting rig of ‘These Constructs’, the viewer encounters each video through a number of possible frames, through apertures in the geometric construction, and through the larger construction itself. The gallery may be taken to serve as an even larger frame again, and indeed the world beyond that. Or, most radically, through the mind, via the eye: light, as an idea, is the primary construct.

‘These Constructs’ reads as a series of short puzzles, games of layered perception. The images move slowly, just enough to be understood as a progression of still images, allowing moments of legibility to be grasped and released. These works stand for perception, embodied apprehension of the world. The way we see, literally and otherwise. Consider the eye, particularly the pupil: a circular aperture that is constantly looked through, but never seen from the inside out. Von Sturmer sets up ricocheting echoes of this analogue, from eye to camera lens, camera lens to torch bulb, torch bulb to projector, to cut-paper screen, back to eye. There is always a lens, the medium through which light passes before it can be seen, and by repeating this motif in the field of vision, von Sturmer sends a diagram of the process telescoping back from world, through sight, to conscious thought.

A construct may be understood as mental shorthand. A reductive, simplified code for a set of complex facts and experiences. As such, constructs — be they cultural, philosophical, social, or otherwise — are useful for ordering and understanding the world, but ‘These Constructs’ suggests that such useful things may also be over-determining. Once a name is given to a set of ideas, that name can become a limit, precluding alternative models of understanding. By reducing the moving image to elegantly minimal, stage-managed screen tests, von Sturmer encourages a recalibration of our expectations of certain cinematic constructs, as analogues for how the wider world might be engaged.

It is notable that the voice has consistently been absent in von Sturmer’s works, which is not to say that it is missing. Where there is a soundtrack in his previous works, it is only the noise of objects themselves, as though any spoken or written text would too easily determine how the images are to be interpreted.

Language tends to take the lead in any study of perception. It shapes, as much as it is shaped by, the way thinking proceeds. Linguistic constructs (grammar, vocabulary) are part of the symbolic order through which the world is accessed, and by each of us, made. And while they do not include the voice, the works are not wordless – the titles of exhibition and individual works set off chains of association that situate the gestures and materials that do, between the linguistic and the visual, begin to make sense.

Visually echoing perception tests used by psychologists, each video in ‘These Constructs’ emits a deadpan cleanliness, invoking scientific objectivity, posing opaque questions whose answers say more about the respondent than the respondent realises. To consider the oddity of perception is to remember that the self is a subjective being, whose experience is fundamentally different to others’. And that while the observed world may be visible and shared, the real object of observation – the mind, and how it works — is always at a remove, abstract, intangible, invisible and radically individual.

Images

Daniel von Sturmer

These Constructs, 2014

installation

Daniel von Sturmer

These Constructs, 2014

installation

Daniel von Sturmer

These Constructs (empty white space), 2014

single-channel High Definition digital video, 16:9, colour

1 minute 8 seconds

Edition of 3

Daniel von Sturmer

These Constructs (laser scans), 2014

single-channel High Definition digital video, 16:9, colour

3 minutes 45 seconds

Edition of 3

Daniel von Sturmer

These Constructs (cutaway black), 2014

single-channel High Definition digital video, 16:9, colour

1 minutes 38 seconds

Edition of 3

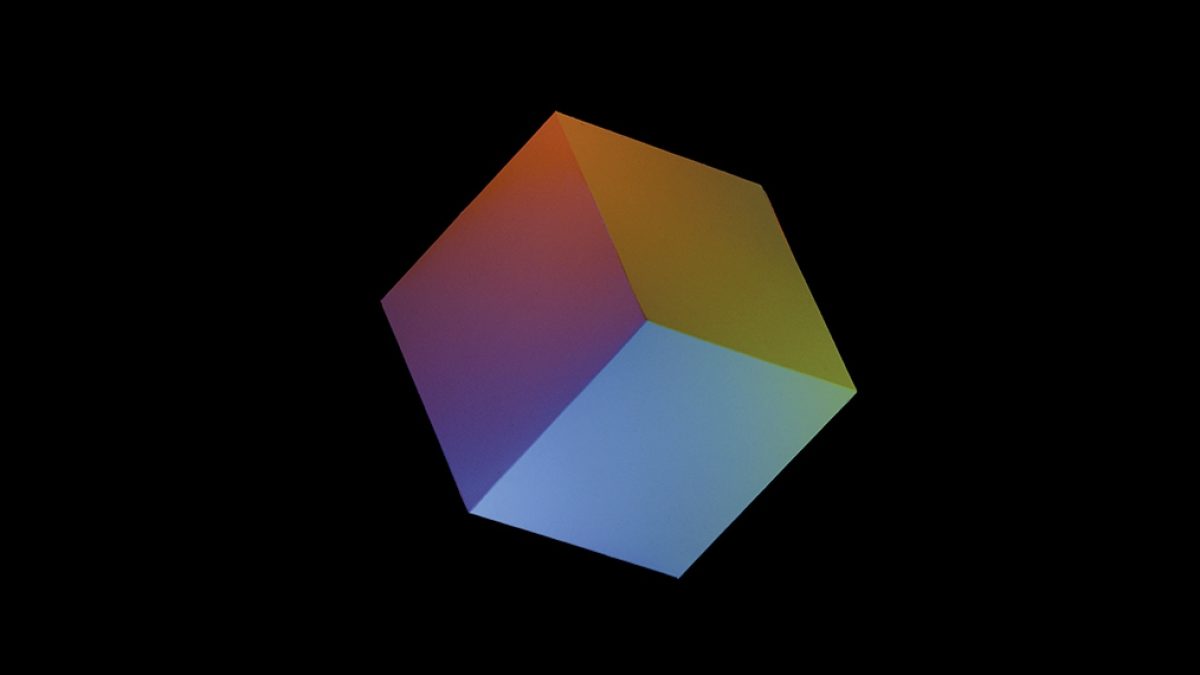

Daniel von Sturmer

These Constructs (RGB cube), 2014

single-channel High Definition digital video, 16:9, colour

1 minutes 46 seconds

Edition of 3

Daniel von Sturmer

These Constructs (flashlight), 2014

single-channel High Definition digital video, 16:9, colour

1 minute 25 seconds

Edition of 3