Callum Morton

Smokescreen

8th October – 7th November 2009

Anna Schwartz Gallery

Recently someone contacted Maroondah City Council in Melbourne enquiring about how one might book a room in my work Hotel (2008) on Eastlink freeway (1). As much as I was pleased to hear this story it did seem strange that such obvious fakery of freeway architecture could be taken for the real thing. Strange also is that security guards and occasional visitors have searched rather anxiously for the lost child belonging to the voice intoning ‘Help me .…. please help me’ inside the work Gas and Fuel (2002) at the National Gallery of Victoria, and that some people thought they had arrived at Le Pine Funeral Homes rather than TarraWarra Museum of Art in Victoria upon observing the Le Pine sign on the entry road that was my work In the Pines (2008).

Yet these sorts of encounters happen regularly enough in recent contemporary art to no longer be surprising.

A curator I know had a few hours to spare in London before his flight back to New Zealand and decided to make a dash to see Frieze Art Fair. When he got there he found himself waiting in one of Roman Ondák’s bogus queues (Good Feelings in Good Times, 2003) believing I guess that it was an entrance queue. After an interminable wait he decided to give up on Frieze and went back to the airport to catch his flight home. It took him till the reviews had arrived before he realised he’d been duped. He thinks Roman owes him at the very least a taxi fare, though it is nice that he can regard himself as a living sculpture. It has happened to me too. I once walked straight past Charles Ray’s blown up life-size toy Firetruck (1993) sitting outside MOCA in LA because I was so keen to see his retrospective inside. When I got out and realised what had happened I was disturbed that I could miss such a large and significant work (one that I was already aware of in reproduction) but equally by what it said about my perception of LA – clearly a Firetruck parked outside a museum should normally alert one’s attention to some sort of trouble.

When artist Danius Kesminas put a large ‘For Sale’ sign (Best Kept Secret, 1994) outside 200 Gertrude Street gallery in Melbourne in 1994, complete with real estate logo and Mondrian inspired graphics, I fell for it and started spreading the news. Context really is everything.

If it is plausible that a work might belong in a certain place then the deficiencies of the simulation are not regarded with such scrutiny, rather they are taken in at a glance. Indeed Hotel’s slightly diminished scale and impossibly thin appearance is intended to underscore the illusion, as was the clearly plastic surface of Ray’s Firetruck and the language used on Kesminas’ billboard: ‘position, position and…three galleries’. These works rely on a distracted state of mind to achieve their effect and the post-industrial city, with its sundry conduits of information delivery, manufactures the perfect nullified audience. Indeed there is so much information to process that ADHD and early dementia become, with each generation, akin to an adapted gene, like some inherited medicated state or stupor. What these works (and many others like them) achieve by being believed for the smallest of moments is indeed not a celebration of this contemporary state but rather a critique of it, an attempt to shake us out of its grip.

The subsequent disorientation that ensues, no matter how brief, is ultimately a poetic one, a rupture or a pause that can at the very least remind us to look up from the screen.

Callum Morton, 2009

Images

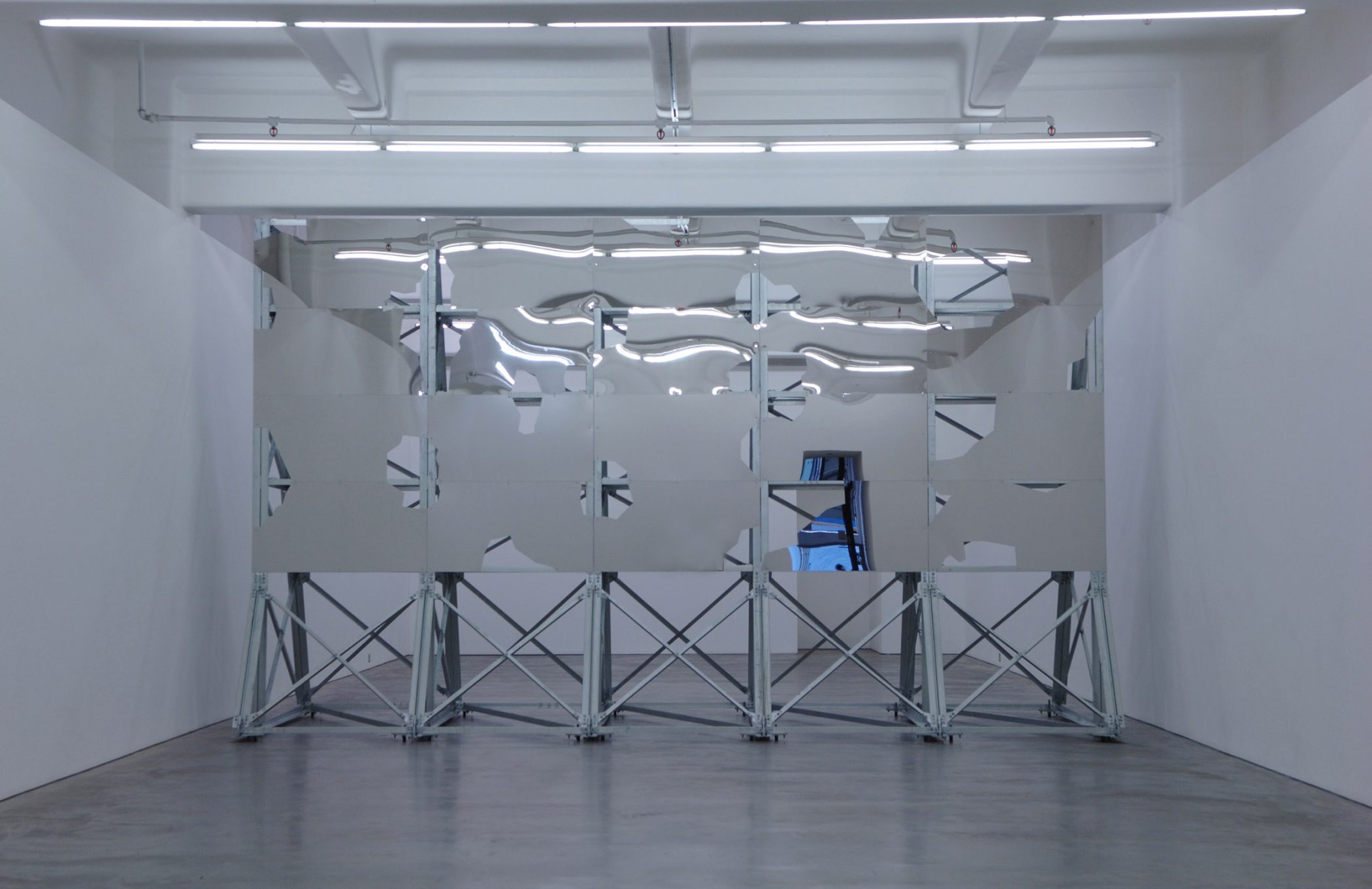

Callum Morton

Smokescreen, 2009

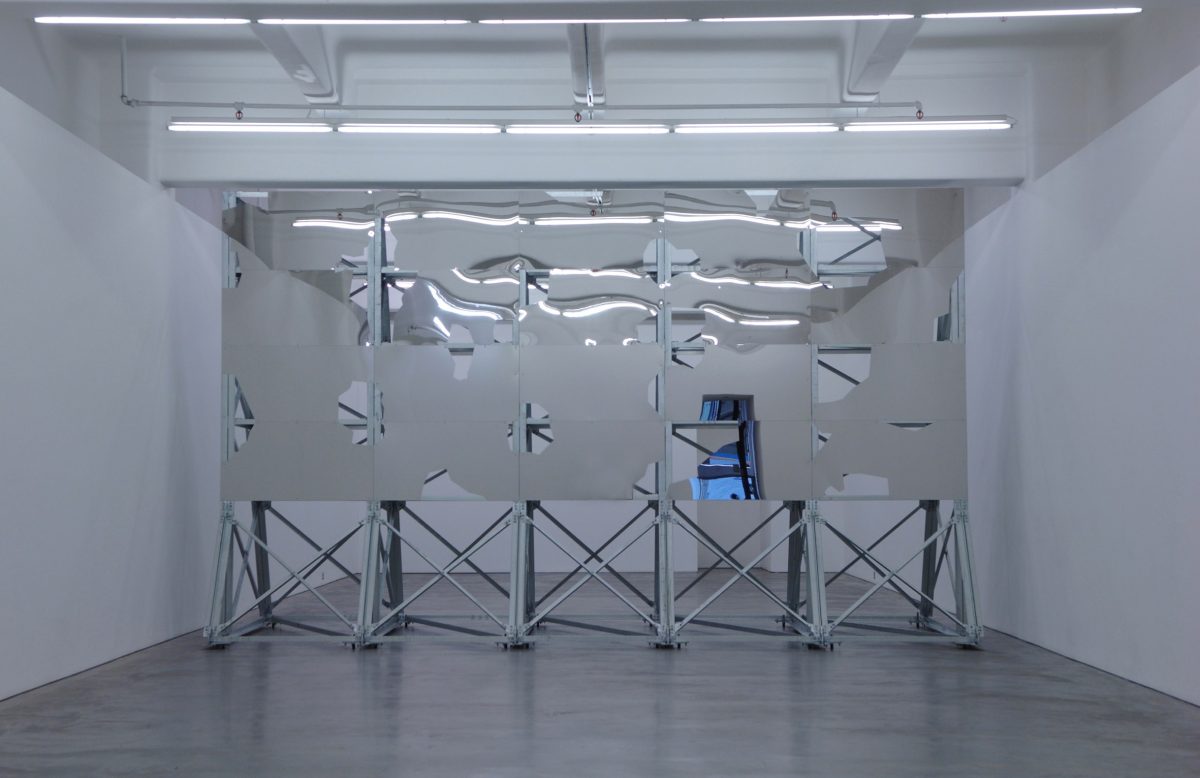

Callum Morton

Smokescreen, 2009

Callum Morton

Smokescreen, 2009