Joseph Kosuth

‘An Interpretation of This Title’ Nietzsche, Darwin and the Paradox of Content

13th February – 10th April 2010

Anna Schwartz Gallery Carriageworks

‘An Interpretation of This Title’ Nietzsche, Darwin and the Paradox of Content

‘A belief, however necessary it may be for the preservation of a species, has nothing to do with truth.’

‘We deny any goals; if existence had one, it would have been reached.’

The discourse of the work finds itself, in a self-reflexive sense, to be a conversation about relations. The device of the work is Friedrich Nietzsche’s relationship with the implications of Charles Darwin’s theories about human evolution. Nietzsche, as John Richardson has persuasively argued, was profoundly attracted to Darwin’s view yet repulsed by what he found to be its dishonesty, that is, by Darwin’s internalization of Christian, and thus moral, values. This corrupted for him much of what was of value about Darwin’s contribution. Yet, Nietzsche was no less influenced by Darwin’s thought and learned from it enough to elicit another approach, one more suitable to his own process of thinking, which reflected a view toward the freedom to ‘self-create’, a state ultimately depending on an aesthetic approach. This was, nonetheless, formed from Darwin’s concept of natural selection. For Nietzsche knowing and revealing ‘who I am’ becomes, for humans, our central task. Earlier selection as a species or as a member of society is part of a process that precedes our consciousness, and it is there where our interior drives and customs are formed. Yet, the process of discover and self-information is the result of our choices throughout our life. These choices are at the service of our will, and are not normally conscious ones, and they provide the opportunity for a new kind of value. Our drives as a species have been inherited and, as well, they are given a form through their use in the history of society. These, in fact, are deeply rooted in our shared drives and shared social history as part of a ‘human herd’, even if we experience them as individual choice. In Nietzsche’s view, the error of the Darwinists was to naturalize the dominant morality and self-justify it as ‘progressive’ through what is basically a retrospective accounting. For Nietzsche, our orderly and apparently purposeful world – – of which science is a part – – is a construction we have put between ourselves and the real world, one which proceeds on its own despite the cultural veneer we place over it. ‘Science,’ Nietzsche writes, ‘has today resigned itself to the apparent world; a real world – – what ever it may be like – – we certainly have no organ for knowing it. At this point we may ask: by means of what organ of knowledge can we posit this antithesis?’

The role of the ‘aesthetic’ here is significant as the role of the artist becomes central to Nietzsche’s view of the potential of humans to find their own capacity for self-creating. Indeed, for Nietzsche the goals of the philosopher and the artist merge as they both attempt an actualization of their own individual potential. The standard ‘will to truth’ in this context becomes instead a warning about the new religion which science represents, as it constitutes a potentially fatal diversion from the aesthetic attitude which leads to human freedom. Freedom, ‘an attained freedom of the will,’ for Nietzsche, is a ‘facility in self-direction. Every artist will understand me.’ In this way philosophizing, always unproven, finds its value not as science but as an activity reflecting aesthetic value, and it’s here where its ultimate meaning is located. It is not much of a leap to then follow the complementary view, my own, which leads to an understanding of the value of artistic production itself fulfilling much of what was once understood as the role of philosophy. Indeed, we can find two quite diverse yet ultimately convergent descriptions of philosophy’s relationship with art, from both Nietzsche and Wittgenstein, both tending toward the view of cultural space increasingly shared by art and philosophy, if not sharing the actual mission itself. Nietzsche’s project, resolving the conflict between the aesthetic and the epistemic, finds itself as a self-realizing existential approach to constructing one’s own ‘view’. The illusion of art becomes a tool to deconstruct the illusions that organize society under the name of truth. The values constructed by art are implicit, are manifested in a Wittgensteinian sense, and, since for Nietzsche ‘truth’ undermines values, the conflict and its aesthetic resolution become clear as the issues are exemplified and articulated. It is the tension of this contradiction that constructs the dialectic of a ‘whole’ upon which this part of his philosophical project can be seen to rest. Here also, through Nietzsche, one begins the possibility of a postmodern project: the necessity to get past science, and modernism’s, need to attempt to grasp their own limits in order to proceed. ‘But science,’ says Nietzsche, ‘spurred by its powerful illusion, speeds irresistibly towards its limits where its optimism, concealed in the essence of logic, suffers shipwreck.’

The drawings of Charles Darwin, as descriptions of a scientific order being posited, are maps of relations as much as representations of the ‘face’ of science as a belief in the making. They constitute both creativity and a ‘truth’ to be. We have a historical view of the formation of our ‘beliefs’ and their exegesis from the hand of a man. We have, in the same space, a horizon line of two texts by Nietzsche which sets the perspective of the total installation: a comment on the play of its parts. This provides both a self-reflection as well as a deeper edification of the work’s combined elements, to be understood and experienced as a ‘whole’ as they simultaneously provide a warning and a critique of the work’s presumptions. Above, on the Mezzanine level, is another kind of map of relations which shadow and illuminate science as constituted by the drawings of Darwin below. The web of connections between these quotes of Nietzsche follow interior arguments concerning art and nature, to art and science, to art and philosophy. This ‘tree’ of relations elliptically self-reflects on Nietzsche’s view of how art, as a construction, serves the self and asserts the self-made. In this view the truth claims of science are put in suspension in order to propose an aesthetic project that, while being located externally, posits an understanding manifested by being asserted indirectly and yet no less as an epistemic restraint, and thus, honestly. As Nietzsche stated, ‘Our ultimate gratitude to art. If we had not welcomed the arts and invented this kind of cult of the untrue, then the realization of general untruth and mendaciousness that now comes to us through science – – the realization that delusion and error are conditions of human knowledge and sensation – – would be utterly unbearable. Honesty would lead to nausea and suicide. But now there is a counterforce against our honesty that helps us to avoid such consequences: art as the good will to appearance.’

Joseph Kosuth, 2009

On 9 Februrary Joseph Kosuth presented a lecture, ‘Public text, stolen text’, at the Art Gallery of New South Wales.

To view the lecture in full, please go to SlowTV:

Images

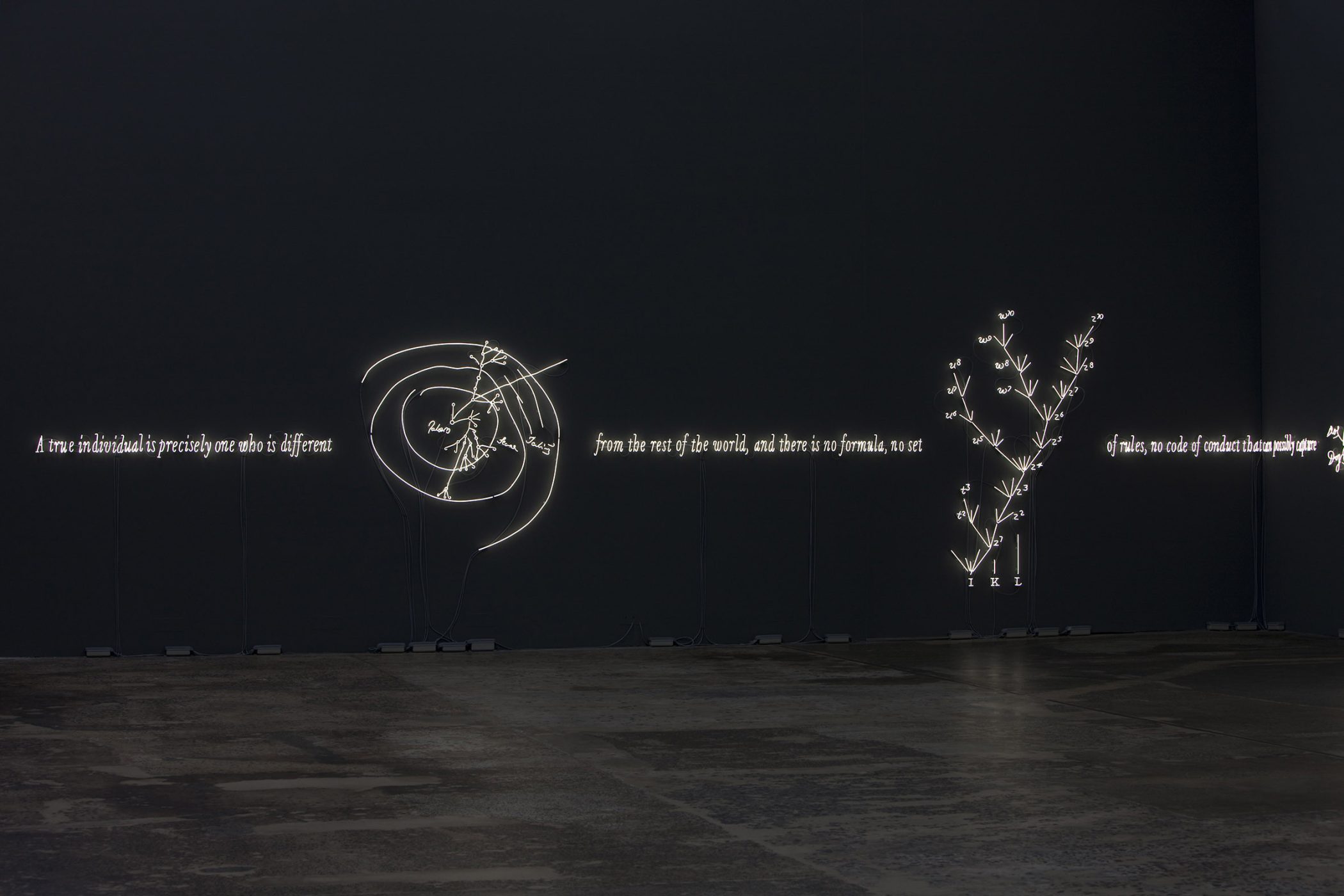

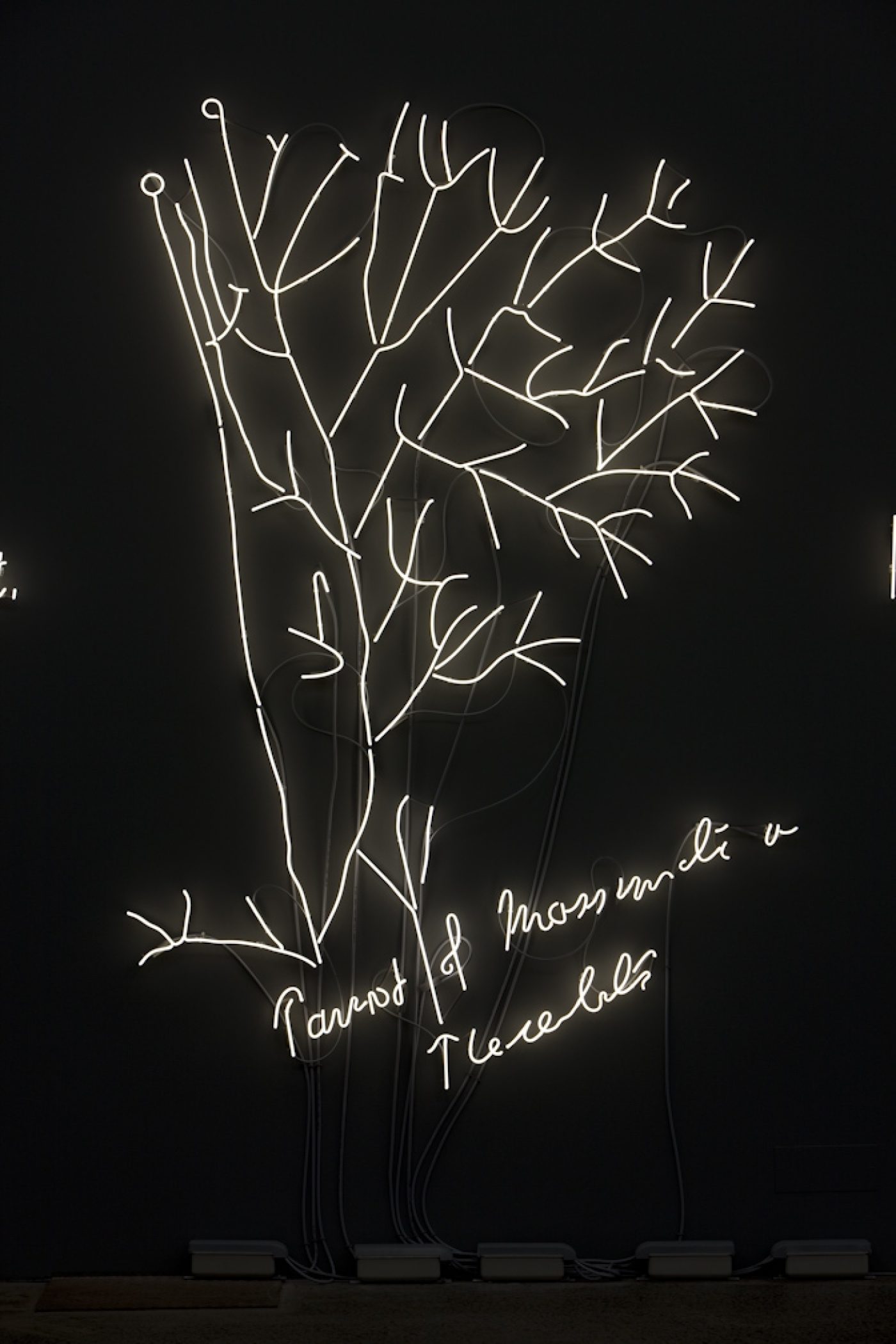

Joseph Kosuth

‘An Interpretation of This Title’ Nietzsche, Darwin and the Paradox of Content, 2010

installation view, Anna Schwartz Gallery, Carriageworks

Photo: Paul Green

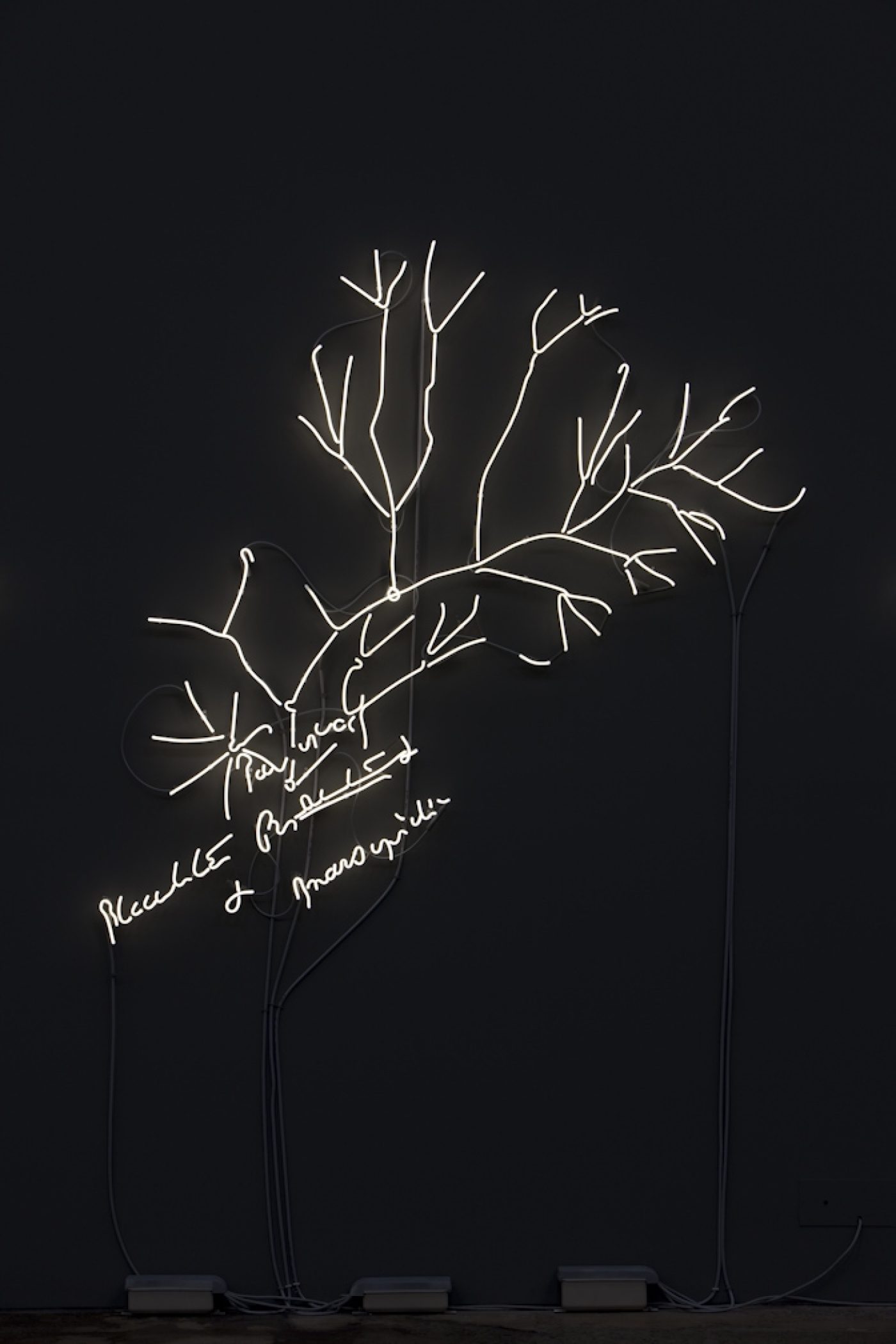

Joseph Kosuth

‘An Interpretation of This Title’ Nietzsche, Darwin and the Paradox of Content, 2010

installation view, Anna Schwartz Gallery, Carriageworks

Photo: Paul Green

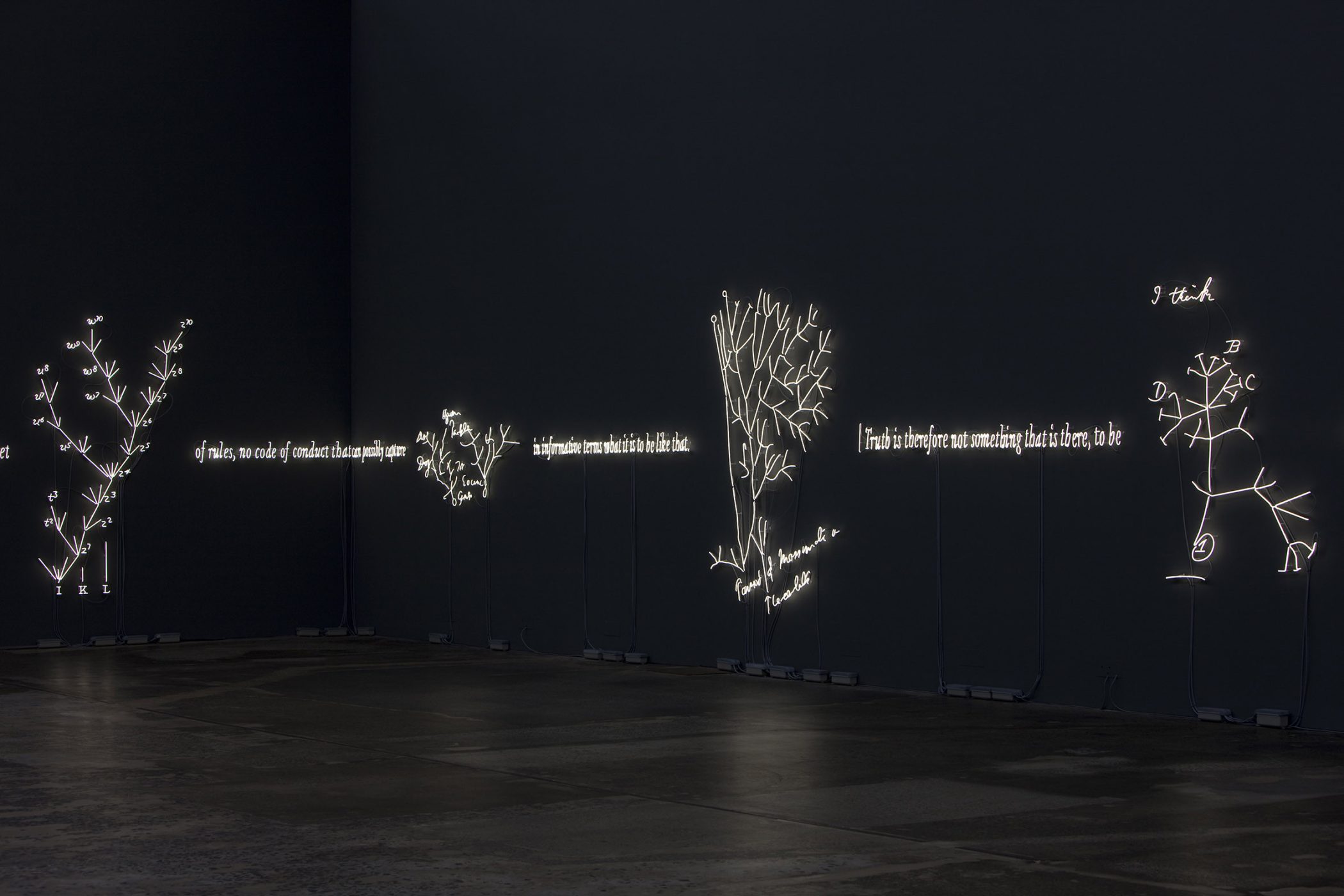

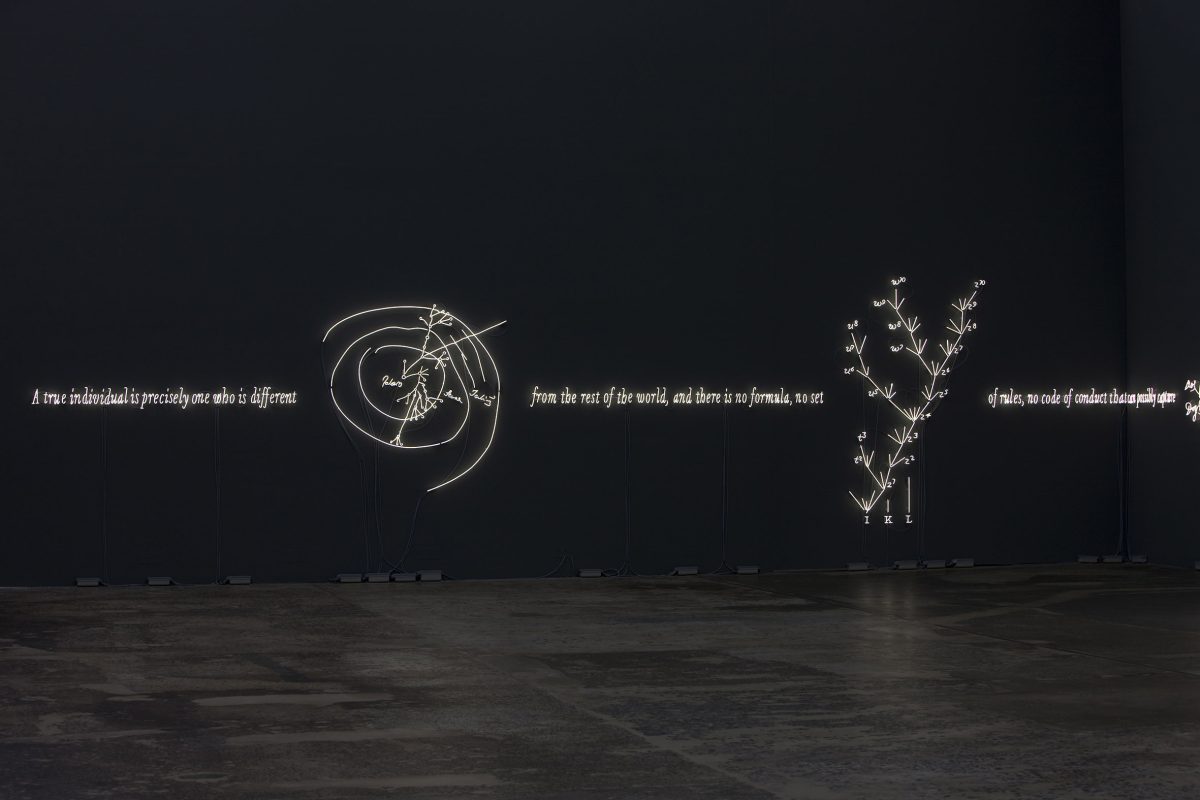

Joseph Kosuth

‘An Interpretation of This Title’ Nietzsche, Darwin and the Paradox of Content, 2010

installation view, Anna Schwartz Gallery, Carriageworks

Photo: Paul Green

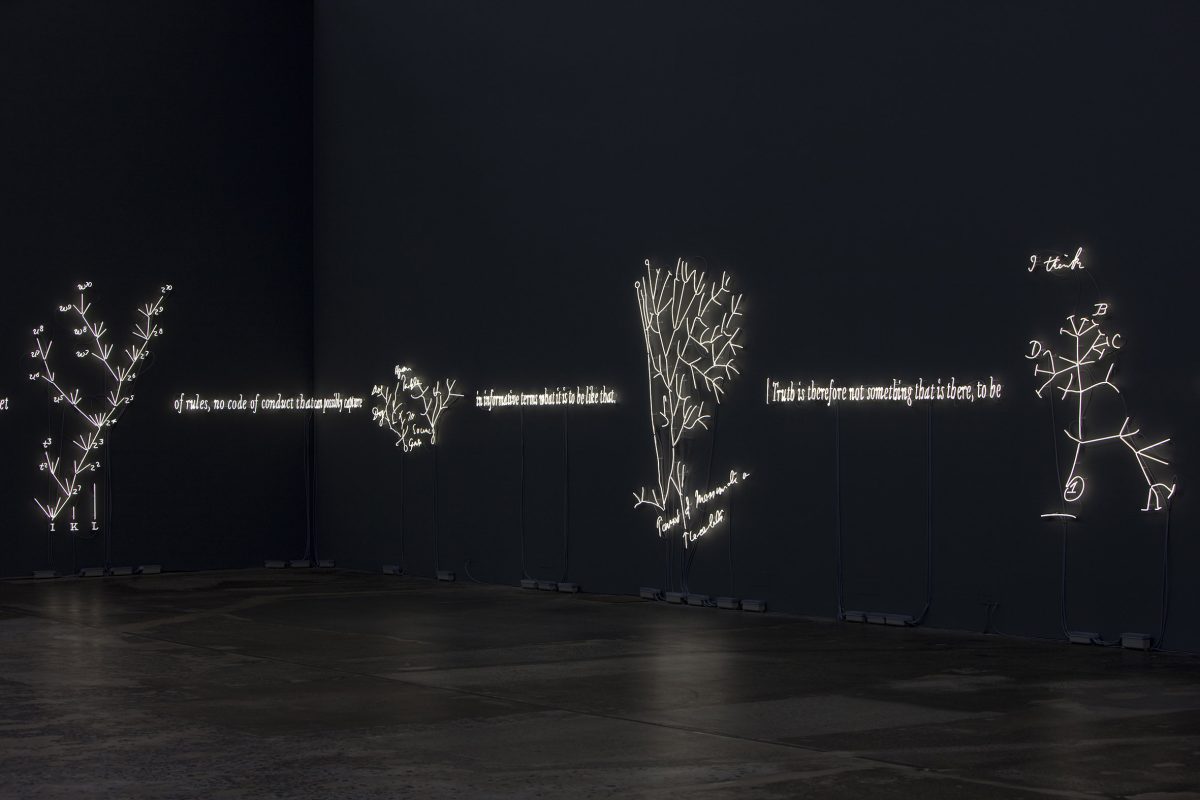

Joseph Kosuth

‘An Interpretation of This Title’ Nietzsche, Darwin and the Paradox of Content, 2010

installation view, Anna Schwartz Gallery, Carriageworks

Photo: Paul Green

Joseph Kosuth

‘An Interpretation of This Title’ Nietzsche, Darwin and the Paradox of Content, 2010

installation view, Anna Schwartz Gallery, Carriageworks

Photo: Paul Green

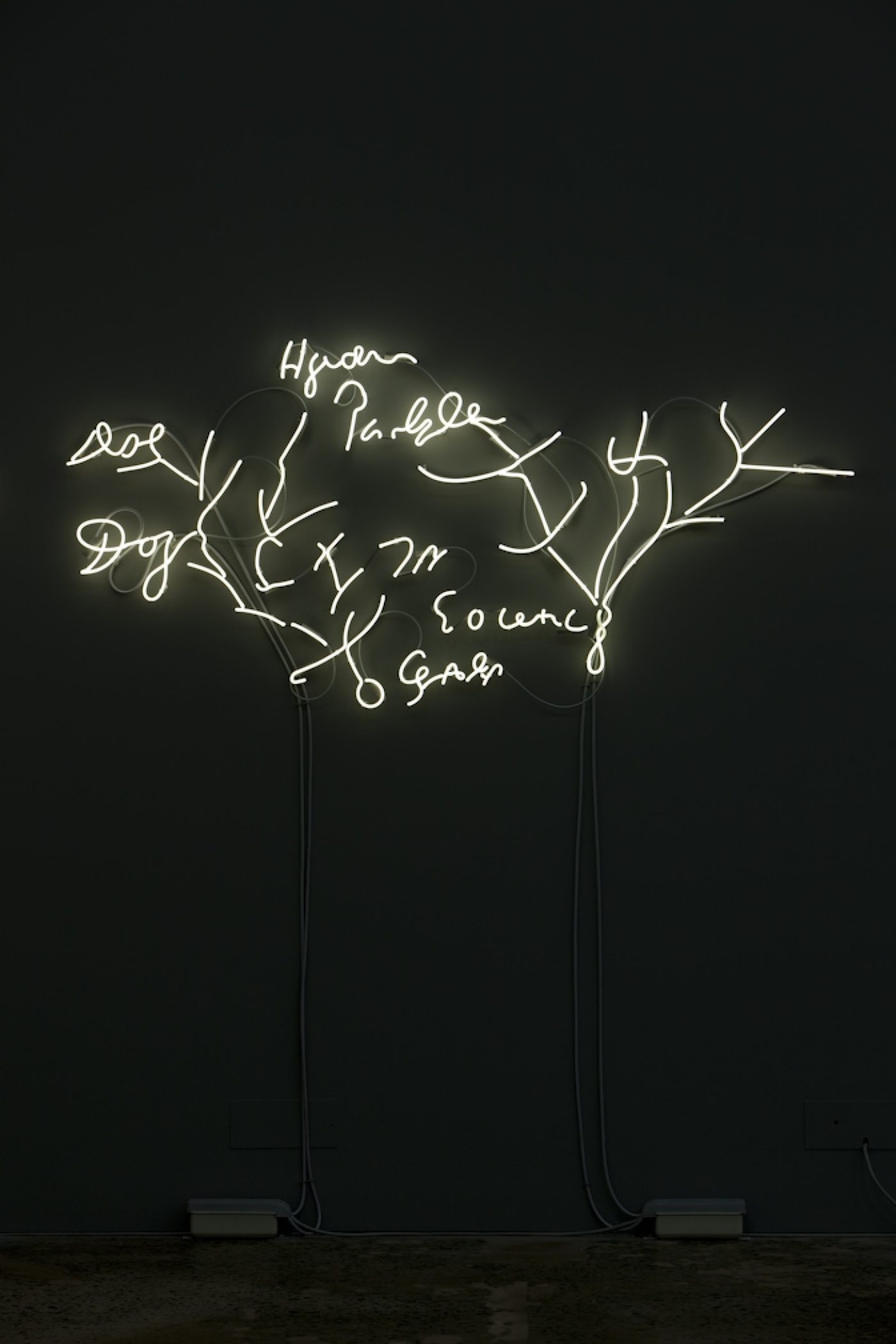

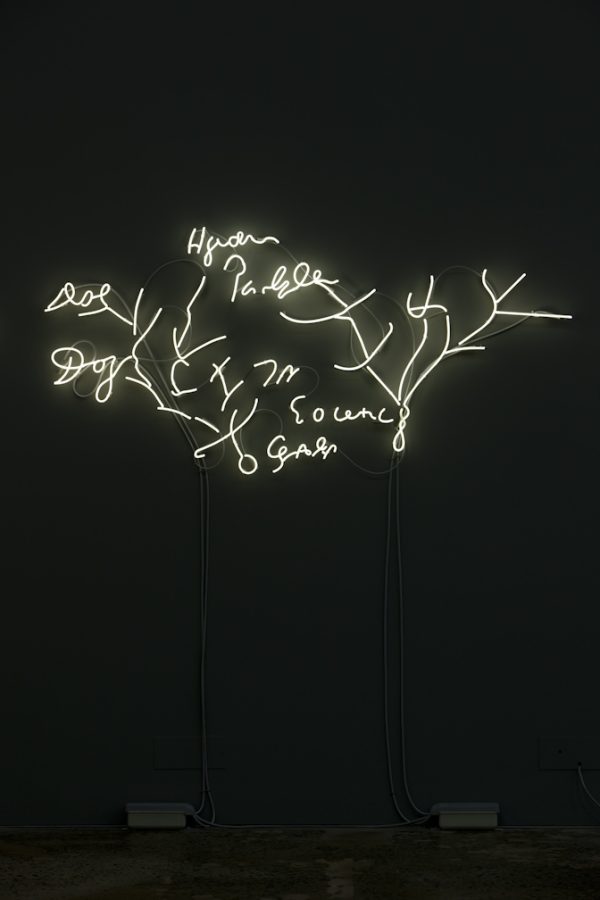

Joseph Kosuth

‘The Paradox of Content #2’ [White], 2009

neon

86 x 182 cm

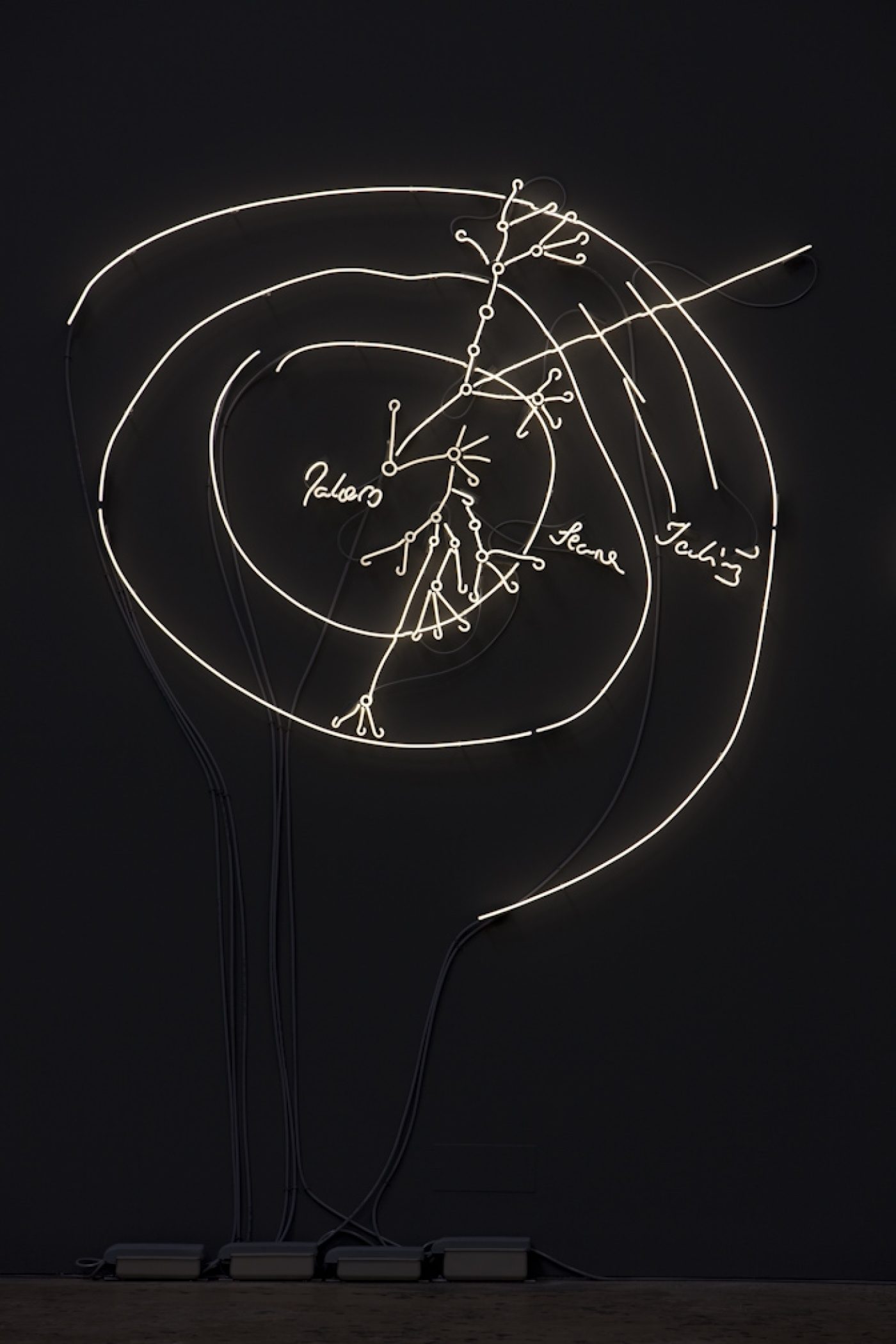

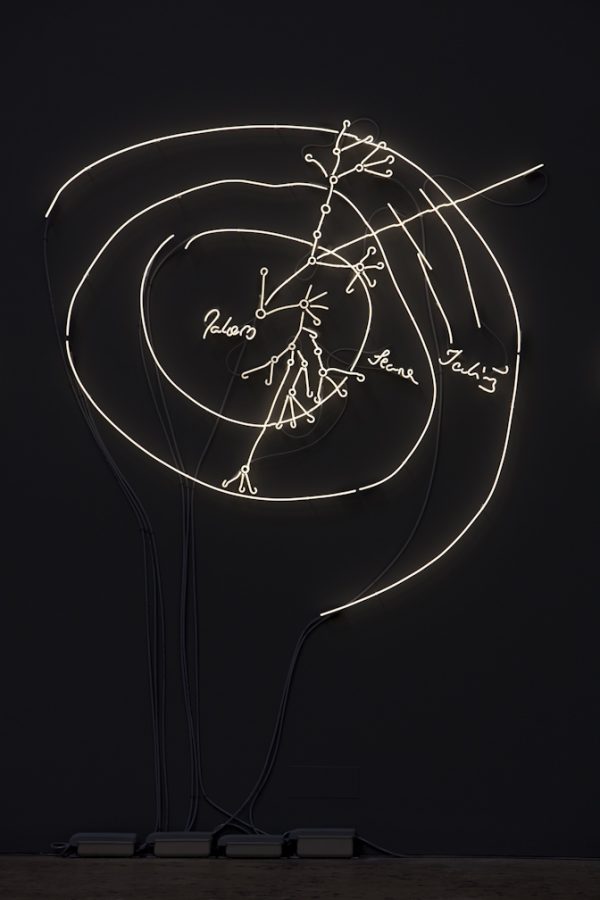

Joseph Kosuth

‘The Paradox of Content #3’ [White], 2009

neon

181 x 183 cm

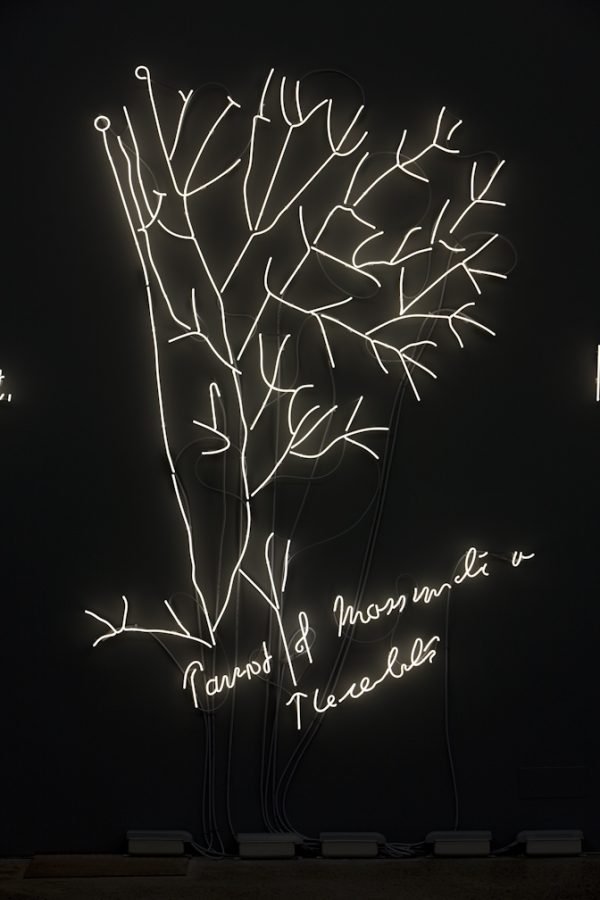

Joseph Kosuth

‘The Paradox of Content #4’ [White], 2009

neon

243 x 164 cm

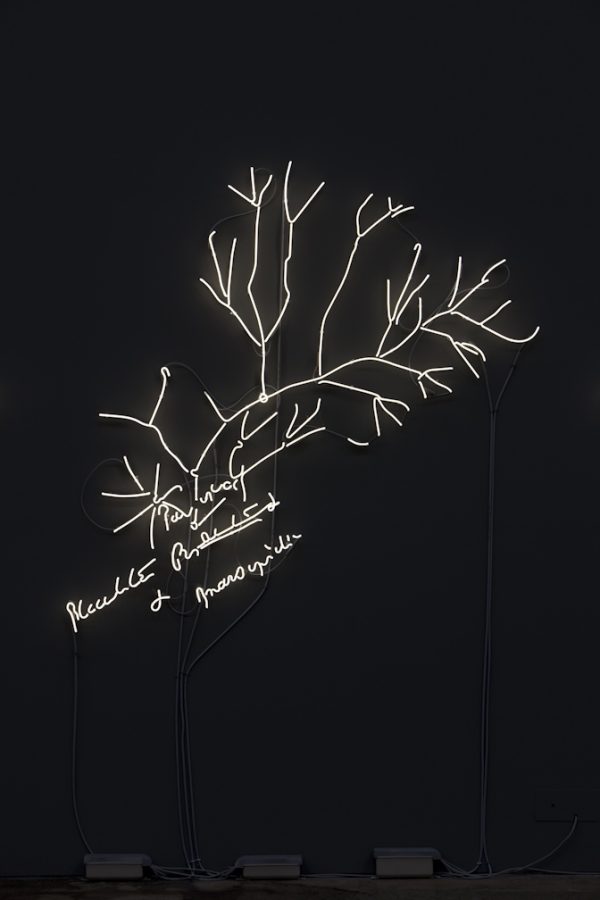

Joseph Kosuth

‘The Paradox of Content #6’ [White], 2009

neon

168 x 167 cm