Heman Chong, Laurent Grasso, Susan Jacobs, Jesse Jones, Jane and Louise Wilson, Ming Wong, Haegue Yang

You promised me, and you said a lie to me

5th October – 9th November 2013

Anna Schwartz Gallery Carriageworks

A thing that is not possible

‘You promised me, and you said a lie to me’ brings together significant works by seven highly-regarded artists, in dialogue with one another for the first time; artists whose practices individually address instances of agency, resistance and vulnerability in the face of interpersonal and political authority.

The title of the exhibition departs from a lament, a ballad of loss. Donal Og, ‘Young Donal’, is traced to the 8th Century and passed on in the Irish tradition of oral storytelling. In Lady Augusta Gregory’s late 18th Century translation, the protagonist claims, ‘You promised me, and you said a lie to me / That you would be before me where the sheep are flocked; / I gave a whistle and three hundred cries to you, / And I found nothing there but a bleating lamb.’ In the original, a loss of self is written into the form of the poem, passed on anonymously, without attribution to an author, from poet to poet. Then through the colonisation of language, in translation from Irish to English, the poem speaks explicitly of loss, ostensibly of love, but also of agency: a lament for how one is constituted in relation to another, the lack of a listener, the potential removal of God from one’s life and the power of redemption. What remains is a question of how agency can be reclaimed; and whether any promise can truly be kept, within the conditions of human fallibility.

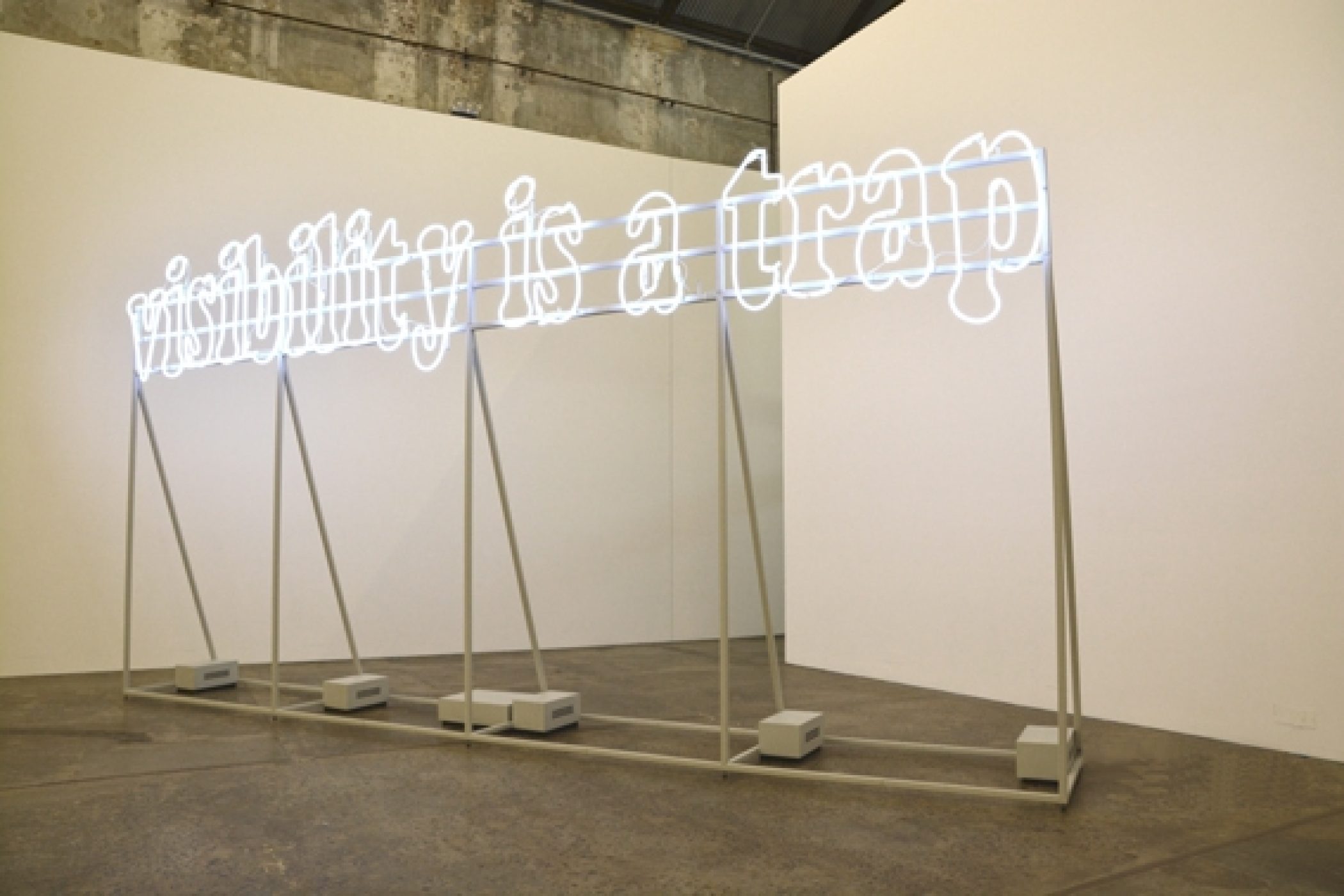

An act of obstruction is the first element in the exhibition installation of ‘You promised me, and you said a lie to me’. Laurent Grasso’s visibility is a trap, a large armature of aluminium, neon and cables, both block and frame the path into the exhibition.

The eye moves swiftly to Jane and Louise Wilson’s works, which draw on their strong interest in cinema, social history and representations of power, and are often underscored with a sense of feminist agency. They use archives as material for rethinking established narratives from particular moments in time, and to find ways to work against systems of authority by excavating new meaning from old situations. In the work False Positives and False Negatives, photographs of the artists’ painted faces are layered over images taken from surveillance footage of the moments immediately preceding and following the Mossad assassination of a Hamas operative in a Dubai hotel in 2010. Taking advantage of the unusual availability of the footage released online by Dubai authorities, which documents all of the events surrounding the assassination except the moment of the killing itself, the Wilsons engage in the practice of hand-painted camouflage. The geometric forms work to obscure the subjects’ identity, scrambling human features in pixel-based video recordings, making the wearers unrecognisable to digital surveillance. This basic form of disguise (a primitive mask-making to effectively deflect sophisticated and secret security technology) reiterates a condition of contemporary society that was brutally laid out by the killing: regardless of the advanced systems available, humans default to the most base acts of murder in order to establish political power over one-another.

This is the first presentation of the Wilsons’ work in Australia since the 1990s, and the materiality of False Positives and False Negatives demonstrates the importance of the moving image in these still works. The images of the artists’ faces, and those taken from the Dubai footage, are printed by hand in layers onto a mirrored surface, mixing digital and analogue and resulting in a series of shifting pictures reminiscent of daguerreotypes.

The Wilsons move from early photography to late-twentieth century film in The Konvas Automat. Through this cast bronze film camera, vision is entirely denied. This piece is cast after the model used by Soviet filmmaker Vladimir Shevchenko in his Chernobyl: A Chronicle of Difficult Weeks, 1986. Shevchenko’s film, pocked with white as if overexposed, was indeed damaged by extreme radiation, and the camera itself was later buried underground in a concrete bunker outside Kiev. The Konvas Automat on its cement plinth is a monument to a man-made catastrophe and the impossibility of ever excavating the full consequences in a way that is possible to comprehend.

Jesse Jones’ works also speak to the difficulty of understanding in an age of decentralised subjectivity. Jones works primarily in film and performance, often adopting techniques of Brechtian theatre and psychoanalysis or enacting other modes of therapy to come to terms with complex political and social situations. In 2008, Jones visited Australia and traveled to the Moon Plain, outside Coober Pedy, working with Melbourne collective DAMP to produce Mahogany, based on the Brecht opera Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny, 1930, to be shown at the Istanbul Biennale. She also filmed a day-long time-lapse sequence that constitutes The Predicament of Man, which premieres here. Each day for the following year, Jones would dedicate an hour to flow-of-consciousness writing, then extract keys words from these texts as online search terms. The database of thousands of images she has built from this exercise flashes past, superimposed over the 16mm Moon Plain footage, allowing the viewer only fleeting glimpses and suggestions of images. The persistent accumulation of images in a saturated, hallucinogenic stream undermines any capacity to formulate understanding from surplus material. There is simply too much information for any knowledge to remain, and the absence of meaning occurs as a consequence of overload.

Heman Chong’s 51 paintings, created especially for ‘You promised me, and you said a lie to me’ from his ongoing Cover (Versions) series, use language to obstruct interpretation. In a strategy analogous to Jones’ image-borrowing, Chong appropriates the titles of books and motifs of graphic design and abstract art to suggest new, if cloudy, meanings. At once strip-mining the histories of late-Twentieth Century painting and design, and contemporary literature, the works are almost visual haiku, evading direct meaning for something less literal, denying the direct communicative power of words.

Abstracting complex situations of Agitprop and systems of resistance into formally compelling sculptural works, Haegue Yang imparts a deep understanding of complex emotional and political situations, freighted in colourful and illuminated assemblages, which are balanced by playfulness and a lightness of touch. Yang’s installation Strange Fruit invokes Albert Meeropol’s poem of that title, made famous as a song performed by Billie Holiday and later Nina Simone. Himself a survivor of the holocaust, Meeropol wrote about lynchings of the American South. Yang often transforms commonplace materials into configurations that surpass the readymade, and here she confers a deeply disturbing character to otherwise innocuous domestic items such as shop-floor clothing racks and imitation plants by taking up Meeropol’s lyrics as her titles. The lamps suspended in elegant jumbles of cabling, painted mannequin hands and suggestive balls of foliage, speak of the lives extinguished by intolerance in public displays of hatred.

Ming Wong’s Actress’ Entrance, from the series Persona Performa, replays a self-conscious moment of public vulnerability, referencing the literal loss of voice of character Elisabet Volger (Liv Ullman) in Ingmar Bergman’s 1966 film Persona. Singapore-born Wong, who learned foreign languages by watching movies and television soap operas, re-deploys moments of world cinema with an almost malicious humour, underscoring stark issues of otherness with a sense of camp, often playing the lead roles in his own re-productions. In Actress’ Entrance, filmed as part of a multi-part live event at Performa, New York, Wong casts actors of different ethnicities and genders in the same role, cutting them together in a repetitious cycle of what is a unique and surprising moment in Persona. Wong’s minimal efforts to apply the same qualities to each actress only amplify their differences and the impossibility of reconstructing the experience of another. As in the works by the Wilsons, Chong and Jones, Wong’s use of repetition reiterates the futility of trying to make disparate personalities confirm to a single identity.

The near-hysterical, comical moment of Wong’s ‘realisation’ plays out in a different form in Laurent Grasso’s visibility is a trap. The neon phrase, mounted on the face of the structure that blocks the gallery’s entrance, illuminates as it obstructs. The text is a sentence from Michel Foucault’s Discipline and Punish, 1971, which deals explicitly with theories of power and occupation, and like Chong’s Cover (Versions), both suggests and denies the possibility of direct communication. “Visibility is a trap… he who is subjected to a field of visibility, and who knows it, assumes responsibility for the constraints of power; he makes them play spontaneously upon himself; he inscribes in himself the power relation in which he simultaneously plays both roles; he becomes the principle of his own subjection” (Discipline and Punish, Vintage Books New York, 1995, p. 200 — 203). Further to openly quoting Foucault’s words, Grasso transforms the statement into a physical manifestation of the power structures that Foucault describes, forcing us by its size and brightness to obey the work’s demand that we see and read it. It is both the first and the final object that is negotiated in the exhibition, and like many of Grasso’s works, it is a challenge: does one accept and believe what one is told, or does one really have the ability to determine what one wants to believe for oneself? Whether engaging with Foucault’s idea of panopticism, medieval scientific and religious belief, or environmental catastrophy, Grasso’s works are a reminder of the place of the complicit political being: when one chooses to believe a lie, then one remains invisible.

Susan Jacob’s work lies at the physical and conceptual core of the exhibition. Commissioned for this space, the installation maps both magnetic north and true north, from the centre of the gallery. The four cardinal points are marked out by sets of objects, each comprising a sliver of cork pierced through with a magnetised steel needle, floating in a vessel of water, connected to cured fish leather. In the middle of this arena is the totemic navel: a heavy steel form, upon which are stacked a vintage hemacite doorknob and a magnet. Jacobs’ title, Ded Reckoning riffs on deductive reasoning, a process of conceptual orientation based on elimination and decision making: one’s place can only be determined by what has preceded. The magnets and magnetic stones, along with the skins of migratory fishes are tools for navigation, as if to be used in the ongoing process of intuitive emotional cartography of everyday life. There is a connection with lived landscapes, in the inclusion of cork, leather and the hemacite (comprised of pigs’ blood and sawdust). There is also a taut material connection to Donal Og, whose protagonist recalls “You promised me a thing that is not possible, / that you would give me gloves of the skin of a fish; / that you would give me shoes of the skin of a bird; /and a suit of the dearest silk in Ireland.” These material promises, not held, hang in the tension of Jacobs’ magentised needles, which in several cases are persuaded away from North by closer, if smaller, magnetic sources. Jacobs makes visible the usually unseen, visceral experiences that are seldom discussed, moments felt as pure vibration, unable to be articulated in language.

In each of the works in ‘You promised me, and you said a lie to me’, there is a constant drive to understand how things move, how the self and the interpersonal map onto the wider social and political field. “You have taken the east from me, you have taken the west from me; / you have taken what is before me and what is behind me”. These works look to the social engagement and formation of public representation that encode who a person is. They ask how it might be possible to operate within and against a system, and to find agency against the authority of social conditions.

Alexie Glass-Kantor, Curator with Ash Kilmartin, Assistant Curator

October 2013

BIOGRAPHIES

Heman Chong (b. 1977, lives Singapore) represented Singapore at the 2003 Biennale di Venezia, Dreams and Conflicts: the Dictatorship of the Viewer. He has participated in international biennales including The 7th Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art, 2012; Performa 11, New York, and Momentum 6, Norway, 2011; Manifesta 8, Murcia, 2010; the Singapore Biennale WONDER, 2008; SCAPE Biennale, Christchurch, 2006; the Busan Biennale, Chasm, South Korea, 2004; and the 10th Triennale India, 2000. His most recent monograph, The Part In The Story Where We Lost Count Of The Days, was published in 2013 by Art Asia Pacific.

Laurent Grasso (b. 1972, lives Paris) was the recipient of the prestigious Prix Marcel Duchamp, 2008. He has participated in the Gwangju Biennale, South Korea, 2012; Manifesta 8, 2010; the Sharjah Biennial and Against Exclusion: 3rd Moscow Biennial, 2009; the Biennale de Lyon, 2007; and the Busan Bienniale 2006 Everywhere, South Korea. In 2012, he presented a major solo exhibition at Jeu de Paume, Paris.

Susan Jacobs (b.1977, lives Melbourne) was included in The 7th Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art, and the Adelaide Biennale, Parallel Collisions, 2012; NEW10, Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, Melbourne, and the Experimental Utopia Now International Biennial of Media Art, 2010. She has recently completed new commissions for the National Centre for Synchrotron Science at Monash University, and for Melbourne Now at the National Gallery of Victoria.

Jesse Jones (b. 1978, lives Dublin) has presented solo exhibitions at Artsonje Centre, Seoul and CCA Londonderry, 2013; The Hugh Lane Gallery, Dublin, 2012; Spike Island, Bristol, 2011; the University of Toronto’s Blackwood Gallery, and Project Arts Centre, Dublin, 2009. Her work featured in the 2010 Glasgow International, and the 2009 11th Istanbul Biennial.

Jane and Louise Wilson (b. 1967, live London) have held solo exhibitions at the British Film Institute Gallery, London and the Musée d’Art Contemporain de Montréal, 2009; BALTIC, UK, 2003; the Serpentine Gallery, London, 1999; and the Chisenhale Gallery, London, 1995. They were included in the 2011 and 2009 Sharjah Biennials, the 2001 SITE Santa Fe Biennial Beau Monde Toward a Redeeming Cosmopolitanism; the 2001 7th Istanbul Biennale; and the 1993 Biennale di Venezia Cardinal Points of the Arts. In 1999 they were nominated for the Turner Prize. They will present a new commission for the Imperial War Museum, London, in 2014.

Ming Wong (b. 1971, lives Berlin/Singapore) has presented work at the Biennale de Lyon, France, 2013; the Liverpool Biennial, UK, 2012; Performa 11 at the Museum of the Moving Image, NY, 2011; the Gwangju Biennale: 10,000 lives, South Korea and the Biennale of Sydney THE BEAUTY OF DISTANCE Songs of Survival in a Precarious Age, 2010. He represented Singapore at the 53rd Biennale di Venezia Making Worlds, 2009, with Life of Imitation, for which he was granted Special Mention in the Biennale’s official awards.

Haegue Yang (b. 1971, lives Berlin/Seoul) represented South Korea at the 2009 Biennale di Venezia Making Worlds. In 2013, she will present a major solo exhibition across multiple venues in Strasbourg. Her work was included in ‘dOCUMENTA (13)’, Kassel, 2012; the 8th Gwangju Biennale 10,000 lives, South Korea, 2010; the 3rd Guangzhou Triennial ‘Farewell to Post-colonialism’, China, 2008; and the 27th Bienal de São Paolo How to Live Together, Brazil, 2006.

Alexie Glass-Kantor is the Director of Artspace, Sydney. From 2006 — 2013 she was the Director & Senior Curator of Gertrude Contemporary, Melbourne. Glass-Kantor has curated widely, collaborating on exhibitions around Australia, the USA, Europe and the Asia-Pacific region, notable highlights being the series of Independence Projects in Malaysia, Singapore, China and South Korea; and ‘Parallel Collisions: 2012’ Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art, co-curated with Natasha Bullock at the Art Gallery of South Australia.

Jesse Jones’ participation in ‘You promised me, and you said a lie to me’ is supported by Culture Ireland.

Images

You promised me, and you said a lie to me, 2013

installation view, Anna Schwartz Gallery, Carriageworks

Curated by Alexie Glass-Kantor

You promised me, and you said a lie to me, 2013

installation view, Anna Schwartz Gallery, Carriageworks

Curated by Alexie Glass-Kantor

You promised me, and you said a lie to me, 2013

installation view, Anna Schwartz Gallery, Carriageworks

Curated by Alexie Glass-Kantor

You promised me, and you said a lie to me, 2013

installation view, Anna Schwartz Gallery, Carriageworks

Curated by Alexie Glass-Kantor

Heman Chong

Cover (Versions), 2009

Acrylic on canvas

Each: 61 x 46 x 3.5 cm

Haegue Yang

Strange Fruit, 2012

Six mixed-media sculptures

Dimensions variable

Laurent Grasso

visibility is a trap, 2012

Neon, transformers, aluminium stand structure

380 x 750 x 100 cm

Jane and Louise Wilson

False Positives and False Negatives, 2012

16 parts, photo-silkscreen on mirrored perspex, framed

Each: 96.5 x 77.5 cm (framed)

Jane and Louise Wilson

The Konvas Automat, 2012

Bronze, concrete

Camera: 25 x 12 x 12 cm; Plinth: 110 x 40.5 x 40.5 cm

Jesse Jones

The Predicament of Man, 2010

Single channel digital video from 16mm and digital flash frames, 16:9, colour

3 minutes

Ming Wong

Persona Performa (Actress’ Entrance), 2012

Single-channel High Definition video, colour, silent

4 minutes