Working Class Hero (A Portrait of John Lennon)

27th July – 28th September 2013

Anna Schwartz Gallery Carriageworks

Look At Me: Who Am I Supposed To Be?

Raimar Stange

I. Fans

A YouTube user who calls himself “Paul McCartney” has posted a homemade video tribute to John Lennon on the World Wide Web. He regularly transmits similar tributes to his idols – including his namesake Paul McCartney – under the programmatic YouTube slogan, “Broadcast Yourself™”. The identification with stardom begins here with a telling pseudonym, and intensifies with every additional portrait that is posted to “Paul McCartney’s” YouTube archive. There is promising evidence here of a phenomenon that various cultural critics have described in relation to the reception of popular culture: “Paul McCartney” appears to be actively engaged in digesting his pop, rather than simply falling passive to its seductions in the mode of a Pavlovian dog.

II.True Fans

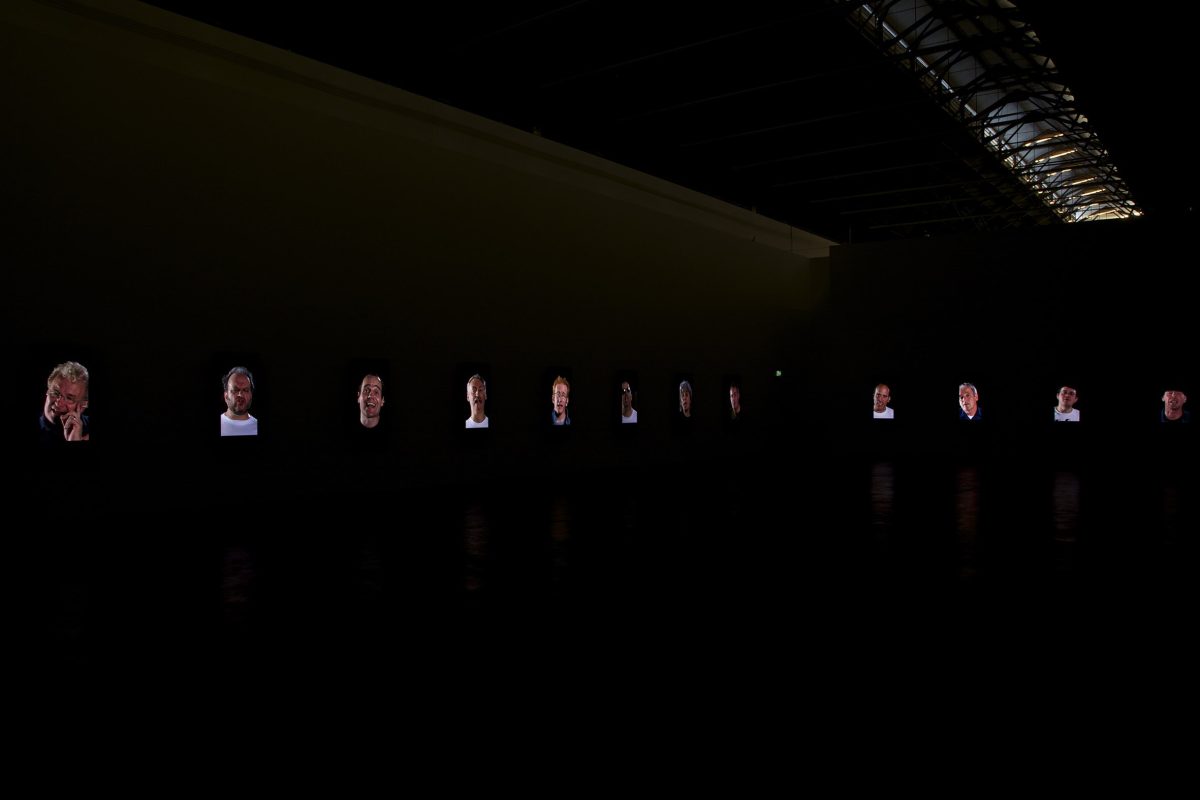

Which brings me to David John Paul George Ringo Lennon, another self-proclaimed fan of The Beatles, and of John Lennon in particular; a fan belonging in this case to a larger community of 25 Lennon fans, who are each portrayed individually on their own separate plasma screen in Candice Breitz’s 25-channel installation Working Class Hero (A Portrait of John Lennon) (2006). Breitz filmed each of the fans re-singing Lennon’s first official post-Beatles solo album, John Lennon / Plastic Ono Band (1970), in its entirety.1 In the final installation, the resulting 25 re-recordings are presented side by side, creating a synchronized 25-strong a cappella version of the album. The fans were chosen from amongst hundreds who responded to ads placed by Breitz. Each respondent was required to fill in a lengthy questionnaire, making it possible for Breitz to zoom in on those whose lives had been most profoundly affected by Lennon: his true fans. Several fans opted out of the project at an early stage, upon realizing that it would focus on the Plastic Ono Band rather than better-known favorites like Imagine and Jealous Guy. The choice of a relatively obscure album was formative to the work that was to result: in choosing Plastic Ono Band, Breitz specifically avoided more mainstream hits in favor of an album consisting of intensely emotional songs that directly relate Lennon’s psychological condition at the time of making the album. In 1970, Lennon signed up for Primal Therapy under the supervision of the psychotherapist Dr. Arthur Janov, an experience which was to set the raw tone of the Plastic Ono Band, and which continues to resonate in the emotional performances of the cast of Working Class Hero.

III. Portraiture

Working Class Hero is a portrait on at least four different levels. Most obviously, Lennon himself is portrayed, albeit in absentia, by his fans and in their recital of his songs. The installation can secondly be regarded as a portrait of the Plastic Ono Band itself, the album portrayed through a series of engaged individual interpretations of its lyrics. Thirdly, Working Class Hero offers a portrait of Northern England, the part of the world in which it was made and from which many of the participating fans hail. Newcastle upon Tyne, the city in which Working Class Hero was shot, is typically post-industrial, having had to gradually redefine itself in response to the decline of heavy industry. The invariable symptoms of such a transition – rampant unemployment and urban redevelopment – find their psychic equivalent in the emotional crisis that is at the heart of the Plastic Ono Band. Breitz’s return to the Plastic Ono Band is fourthly, and above all, a portrait of the participating fans: the manner in which they take possession of their idol’s music must ultimately be read to reflect – consciously or not – their own lives and desires. Lennon clearly understood the potential or identification that is latent in the extremely intimate songs that make up this album: when he introduced the song Mother at a concert in New York in 1972, he commented that, “a lot of people thought [this song] was just about my parents; but it’s about 99 percent of the parents, alive or half-dead…” Drawing on Mikhail Bakhtin, John Fiske has described this phenomenon – the emergence of new narratives as a result of the layering of personal experience onto the products of the mass media – as a form of “Heteroglossia”. 2 The active reception of given content has the potential to generate personal experiences, longings and reflections, which are woven into the content of the original songs, creating a new language. “Heteroglossia” eloquently describes the possibilities and limitations that are inherent not only to the language of pop, but also to language in general. The linguistic utterances of an individual must necessarily make themselves heard against the backdrop of a pre-existing shared language.3 The fans in Breitz’s installation identify with Lennon not only by means of their John Lennon T‑Shirts and round wire-rimmed glasses, but more importantly through their complex individual embodiments of the Lennon that each imagines.4 In his reflections on Cindy Sherman and Madonna, the philosopher Wolfgang Welsch refers to this process of embodiment as “identity in transition.” The English language grasps the complexity of “identity in transition” better than German can: where the German word “Imitator” evokes superficial mimicry, the English word “Impersonator” suggests an altogether more complex process of embodiment.

IV. The Anthropology of the Fan

Working Class Hero is the fourth in an ongoing series of portraits by Breitz, preceded by Legend (A Portrait of Bob Marley), King (A Portrait of Michael Jackson), and Queen (A Portrait of Madonna), all dated 2005.5 The portraits have thus far followed the same procedural logic. Each of the selected fans is offered the opportunity to re-perform a complete album in a professional recording studio. The fans are then presented

non-hierarchically alongside each other, in grid-like formations that privilege no fan over any other: each performer is granted the same verbal and visual presence. Stark differences between the four portraits are nevertheless apparent: it is clear that each of the stars chosen for portrayal has a very particular public persona, which in turn attracts a very specific community of fans. The location chosen for the shoot is itself particular in each case: the portrait of Bob Marley was shot in his home country Jamaica, with the help of a cast of local fans who re-sung the compilation album Legend (1984). Madonna’s greatest hits compilation, The Immaculate Collection (1990), was re-performed by thirty Italian fans in a studio in Milan, while the translation of Michael Jackson’s Thriller (1982) album was left to sixteen German-speaking fans who traveled to Berlin to participate. Legend is characterized by the laid-back flair of the Caribbean and the relaxed relationship of Marley’s fans to the beloved music that they interpret. The sexually loaded Queen throws up multiple references to Madonna’s gender-bending tendencies, just as it vividly evokes the energy of the lively Italian metropolis of Milan. Finally, King, which was produced in hip Berlin, illuminates not only the glamour of the Jackson phenomenon, but also the fragility of this complex pop figure. As one moves from one portrait to the next, an anthropology of fandom gradually begins to emerge, a study of the fan that traverses the spectrum from fans whose identification is lodged in a shared national identity, to fans whose identification resides in the very rejection of fixed identity, to fans who express their identification through intense mimicry and self-erasure. In exploring the cathartic dimension of the Plastic Ono Band, Working Class Hero broadens this anthropology of the fan yet again. Just as Lennon himself underwent Primal Therapy, the fans who participate in this portrait seem to undergo a parallel Plastic Ono Band therapy, probing their personal psychological crises as they move through the album.

In closing, I would like to draw a parallel – which may at first seem surprising – between Breitz’s portraits and August Sander’s life-long social portrait Citizens of the Twentieth Century. Sander’s quasi-scientific approach to documenting the people in his immediate surroundings is echoed in Breitz’s endeavor to map the anthropology of the fan. Her portraits set the conditions for an ongoing series of typological studies of “the fan”, as each of the participants steps into the laboratory-like studio to offer their version of the same album under the same conditions. In the place of Sander’s subjects, who are defined by their occupations, Breitz’s fans are defined by that which they consume, as expressed in their idiosyncratic reception and translation of the music that they love. This shift – from Sander’s working citizens to Breitz’s fans – marks a broader historical shift, from the cult of production that characterized modernity to the postmodern eclipse of production by the culture of consumption.

Endnotes

1. Pop Idol also presents ordinary people singing popular hits, though the participants do not necessarily define themselves as fans. Unlike Breitz’s fans, participants in this and similar programs are earnestly intent on becoming stars themselves. 2. See John Fiske Reading the Popular (London: Routledge, 1989) 3. Breitz explores this logic in her ten-channel video installation Karaōke (2000), in which ten participants each contribute expressive Karaōke performances of the English version of Roberta Flack’s song Killing Me Softly, despite the fact that English is not a native tongue for any of the singers. 4. See Wolfgang Welsch Ästhetisches Denken (Stuttgart: Reclam, 1990) 5. The first part of the title of each portrait was chosen after Breitz had interviewed each community of fans, and reflects a term commonly used by the fans to describe their idol.

Raimar Stange,“Look at Me: Who Am I Supposed To Be?” in Christine Kintisch (editor), Candice Breitz: Working Class Hero, (Vienna: Bawag Foundation, 2006) exhibition catalogue.

Images

Working Class Hero (A Portrait of John Lennon), 2013

installation view, Anna Schwartz Gallery, Carriageworks

Photo: Paul Green

Working Class Hero (A Portrait of John Lennon), 2013

installation view, Anna Schwartz Gallery, Carriageworks

Photo: Paul Green

Working Class Hero (A Portrait of John Lennon), 2013

installation view, Anna Schwartz Gallery, Carriageworks

Photo: Paul Green

Working Class Hero (A Portrait of John Lennon), 2013

installation view, Anna Schwartz Gallery, Carriageworks

Photo: Paul Green

Working Class Hero (A Portrait of John Lennon), 2013

installation view, Anna Schwartz Gallery, Carriageworks

Photo: Paul Green

Working Class Hero (A Portrait of John Lennon), 2013

installation view, Anna Schwartz Gallery, Carriageworks

Photo: Paul Green

Working Class Hero (A Portrait of John Lennon), 2013

installation view, Anna Schwartz Gallery, Carriageworks

Photo: Paul Green

Working Class Hero (A Portrait of John Lennon), 2013

installation view, Anna Schwartz Gallery, Carriageworks

Photo: Paul Green

Working Class Hero (A Portrait of John Lennon), 2013

installation view, Anna Schwartz Gallery, Carriageworks

Photo: Paul Green

Working Class Hero (A Portrait of John Lennon, 2013

installation view, Anna Schwartz Gallery, Carriageworks

Photo: Paul Green