Shaun Gladwell

The Inspector of Tides

30th October – 19th December 2015

Anna Schwartz Gallery Carriageworks

THE INVENTION OF THE SKATEBOARD IS THE INVENTION OF THE SLAM

Time and tide wait for no man.

Geoffrey Chaucer

The road up and the road down are one and the same.

Heraclitus

Shaun Gladwell is a highly accomplished freestyle skateboarder, enough so to have been amateur champion of the world, and his own skating has often been the focus of his work as an artist. Skateboarding seems to me to be more than just convenient content for the work; it actually functions as a generative principle, one to which Gladwell ceaselessly returns, and also as the model for something like an ethic.

Freestyle is the minimalist form of skateboarding. You don’t need any special terrain, like the curved walls used by vert skaters, the ledges and gaps sought out by street skaters, or the mountain roads beloved of speed skaters. All you need is a flat, hard, smooth surface. It is also the most rarely pursued, esoteric form of this sport that is not really a sport; a combining, hyperactive, yet reflective discipline that takes the basic kinetic vocabulary of skating – moves such as balancing, spinning, flipping, popping, and sliding – and endlessly recombines and morphs them into each other to create new, unexpected forms. It is like action painting without the paint.

It is significant that Gladwell eternally returns to Bondi Beach, both as a skater and as an artist. Skateboarding began as ‘sidewalk surfing’, a way of bringing the wide open freedom of the seas into the controlled environments of modern cities and suburbs. A skateboard, then, is already a tool for exploring urban spaces in ways never intended by their designers. Handrails meant to control and normalise movement become opportunities to explore new forms of ecstatic motion; useless abandoned swimming pools are used to test the possibilities of life on the vertical plane. Freestyle does the same thing with the skateboard itself. Freestylers like Gladwell will find ways to ride their boards on just two wheels (wheelies and manuals), spinning on just one wheel (one wheel 360), jumping up and down on the tail (pogo), sliding on the side edge (primo), or even flipping the board and riding on its underside (darkslide). There are no rules or pre-set goals to this experimental practice, just the constant process of discovering and differentiating all the ways a board and a body can move in relation to each other.

Watching Gladwell skate in real life is mesmerising. His board and body are constantly spinning and flipping, sometimes in concert, sometimes in different directions, and he is always initiating the next trick before you have had time to comprehend the last. It is like watching an impossibly dextrous magician doing lightning-fast card tricks, except that Shaun is not only shuffling the cards, he is riding them, being shuffled by them in return. Freestyle is this art of self-shuffling. It is an intensely centred, centripetal activity, but there is also an expansive movement in Gladwell’s freestyle performance: the spectacle he creates draws in passersby, who will randomly stop and engage the performer in conversation. The number of people who recognise and feel motivated to approach him grows each time he returns to his favourite spot at Bondi. Even as he engages in the utterly centred activity of freestyle, he is networking, forming a kind of intermittent community, shuffling newly found friends into his ever-growing pack. Gladwell’s entire life seems to be determined by a similar dynamic at the global level. As soon as he arrives somewhere, he is already leaving. It is as though he were deliberately constructing his life as a kind of freestyle routine. This seems to be exactly how his art works, as evidenced in this very exhibition: a growing network of collaborators juxtaposed with the artist’s eternal return to his own questions, his own emerging ‘traditions’, his own obsessive love for certain repeated motifs: spinning bodies, inversions of body and world, the use of video to distort and distend time, the iconography of Mad Max films, art history and theory, skateboarding itself.

Self Portrait Spinning and Falling in Paris (2015) is a repetition and transformation of earlier works focussed on the artist skateboarding or otherwise interacting with designed environments in strange and unexpected, often literally ‘upside down’ ways.

The decisive precedent, of course, is the breakthrough work, Storm Sequence (2000), which already features Gladwell himself doing freestyle in slow motion. In traditional sports coverage, slow motion allows viewers to interrogate a decisive moment of action. We are permitted to re-watch a privileged instant stretched out to the length of an ordeal in order to more fully appreciate the complex play of forces converging upon a single moment. There is no such hierarchy of moments in Gladwell. Instead, he repeatedly chooses to subject entire events to the effects of slow motion. Each gesture seems to unfold like a flower or a work of origami, the moving body crossed by contending rhythms that uncoil at different speeds through muscles and limbs that no longer seem to be defined by the teleology of a single purpose. There are waves and tides rising and converging from every direction in Storm Sequence, not only in the sea, or in the turbulent sky above, but also in the performer’s own body, the different parts of which flex and rotate and respond to each other in ways that are visibly too complex to be consciously monitored or controlled in real time by the performer. Gladwell’s own body is like a river mouth opening to the ocean, crossed by waves and tides driven by and returning to a single source that nonetheless tend to separate and sometimes conflict according to their own internal dynamics, but it is also like a twig or a surfboard cut loose from its tether, caught up in this criss-cross play of waves and tidal forces. The intensity and complexity of the staged performance is as crucial as the slow motion, which functions not just as an ‘effect’ added to the content, but as an expression of that content, revealing a certain kind of passivity at the heart of every action as time ceases to function as the measure of an accomplishment in space.

Self Portrait Spinning and Falling in Paris, (2015), which shows the artist visiting various sites in Paris and spinning multiple 360s on his skateboard, takes this now instantly recognisable ‘Gladwellian’ format to another level. The level at which the artist/skater is seen falling like a helpless ragdoll at the end of each performance.

When the artist first showed me this footage, I almost fell over backwards myself, laughing. It wasn’t so much the slam at the end; it was the fact that this very high definition, extreme slow motion footage somehow made my friend look prematurely decrepit. Here he was, spinning these 360s which are so impressive to witness in real life, but instead of looking like the enviably youthful Master of His Own Body I know him to be, he looked somehow worried, weirdly awkward, as if he were afraid he might keel over at any moment. Indeed, the only time one usually sees a human being devoting such intense attention to the mere task of staying upright is when encountering an infirm person trying to navigate their way through space with the aid of a Zimmer frame. If the slow motion of Storm Sequence (2000) already released Gladwell’s body from the ‘gee-whizz’ impression of action commanded by the head, this much clearer, more detailed footage exposes the ‘self-care’ expressed in the artist’s face and outreaching arms as he is caught up in a wave that he has generated from within himself, the instinctive caution that keeps him upright in the spinning centre of his own performance.

And then, at the end of performance, the artist falls. How to understand these concluding catastrophes?

Another work featured in this exhibition quotes the philosopher Paul Virilio to the effect that “The Invention of the ship is the invention of the shipwreck”. This is just one way in which Virilio expresses his thesis that every technology necessarily implies a new form of accident. We are thus also assured that the invention of car is the invention of the car crash, and not just as a side effect. Rejecting Aristotle’s founding metaphysical opposition between essence and accident, Virilio insists that the accident IS the essence. In Negative Horizon (2005), he tells a parable about a man driving a car down a highway, feeling insulated and secure in his speeding metal bubble as he effortlessly penetrates space, the world unfolding across his windscreen on command. This sense of control and safety is suddenly shattered when a collision forces the driver to learn the truth about the relation between technology and accident in the most intimate possible way. It is already too late for the driver to reflect as his body is sent careening through the windscreen, finally breaking the ‘fourth wall’ of vehicular spectatorship as he is projected towards the vanishing point of his own death.

Put Gladwell in a car burning down a desert highway and he will voluntarily climb out the window and stand on the roof (Interceptor Surf Sequence, 2009). He will, in other words, do his best to turn the car into a skateboard, a form of transport that has no insulating bubble, in which the imminent possibility of crashing or falling can never be forgotten; in which the accident is not disavowed as ‘merely’ accidental, but fully and lucidly embraced, becoming the very motivation of movement, even as the rider deploys all his concentration and skill trying to ensure it doesn’t happen.

If the prang is the essence of driving, the slam is the essence of skateboarding. Or rather, of the skaterly, since Gladwell often extends this approach beyond the world of skating.

There may be little trace of narrative in many of Gladwell’s videos, but there certainly is a kind of drama. In Tangara (2003), the overhead support of the train carriage is designed to help humans avoid falling, to minimise the dangers of mass transit, but Gladwell deliberately uses it to increase the risk of falling, to raise the stakes of every move he makes. The simple decision to invert the function of designed space provides a kind of dramatic physical premise that puts the performer’s body at risk of injury and pain. Gladwell in this way takes the neutral space of a mass vehicle made to transport docile bodies from A to B and turns it into a world of unexpected possibilities: a tightly defined world where the body is intimately constrained by metal structures and yet ceaselessly seeks new degrees of freedom afforded by those very constraints.

These inversions of function occur throughout the performances featured in Gladwell’s art, especially when it is his own body being put on the line. In A Guide to Recent Sydney Architecture (2000), as well as Storm Sequence, it is the addition of water to the skating surface, the very thing skaters usually avoid. In Approach to Mundi Mundi (2007) it is the act of letting go of the handlebars of a speeding motorbike so that it must be controlled purely by balance instead of steering, just like a skateboard.

I would suggest that physical pain has a very different tone in Gladwell’s recorded performances than in the work of other artists who have publicly subjected themselves to the effects of gravity while suspended from various forms of apparatus. Where others passively endure the tortures of a pre-defined condition, Gladwell uses pain as one feedback path among others in timing actions that subvert the very distinction between the passive and the active. Pain is never the point, nor is it enough to bring the search for new forms of motion to a stop. The tone here is ultimately affirmative, even optimistic. All it takes to create a world is a human body, a constrained environment, the possibilities of movement that can be discovered in their relationship, and the joyful embrace of physical risks implied by that exploration.

What I see watching works like Self Portrait Spinning and Falling in Paris, (2015) is less the pathetic search for balance and equilibrium in a space devoid of gravity, or the evocation of an alienated life in which the artist hides from the world inside his own spinning ghost, than a body seizing the chance to raise the stakes of every action. Gladwell’s work is a coherent, ongoing affirmation and exploration of this ethic of the skaterly. Of course, you don’t skate to fall; you do everything you can stop it happening. But you do skate because you could fall, because the stakes of every move, every decision, are raised by the constant prospect of slamming. Nietzsche taught that cruelty is the best mnemonic system, the most efficient way to engrave memories into the folds of the human brain: for a skater, that cruelty is the force of gravity constantly threatening to bring the body into direct relationship with concrete. If the very ubiquity of gravity ensures that it remains ‘invisible’ for terrestrial beings under ordinary conditions, the extraordinary effect of Gladwell’s work is to render gravity visible. In short, to defamiliarise the most familiar thing on earth: the very fact that we are stuck on it.

Dr Bill Schaffer, pool skater and film scholar

Images

Shaun Gladwell

The Inspector of Tides, 2015

installation view, Anna Schwartz Gallery, Carriageworks

Shaun Gladwell

The Inspector of Tides, 2015

installation view, Anna Schwartz Gallery, Carriageworks

Shaun Gladwell

Self Portrait Spinning and Falling in Paris, 2016

single-channel High Definition video, 16:9, colour, silent

15 minutes 26 seconds

Shaun Gladwell

John Forrest Backside Invert, 2015

inkjet print on paper

183 x 123 cm

Edition of 2

Shaun Gladwell

Tower Bridge Frontside Invert, 2015

183 x 123 cm (framed)

Shaun Gladwell

Cosmology (Air Antwerpen), 2011

Enamel on aluminium panel

123 x 123 cm

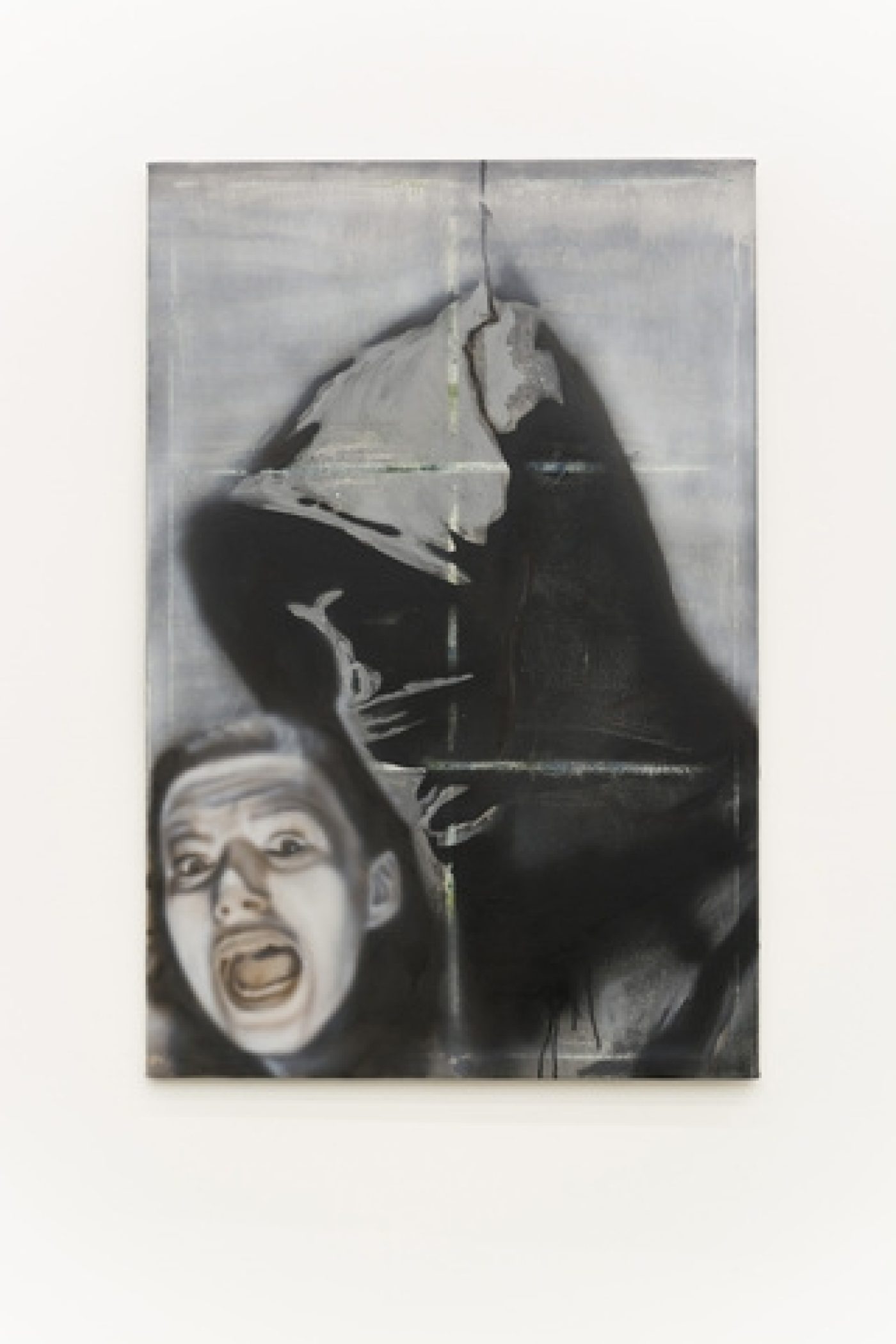

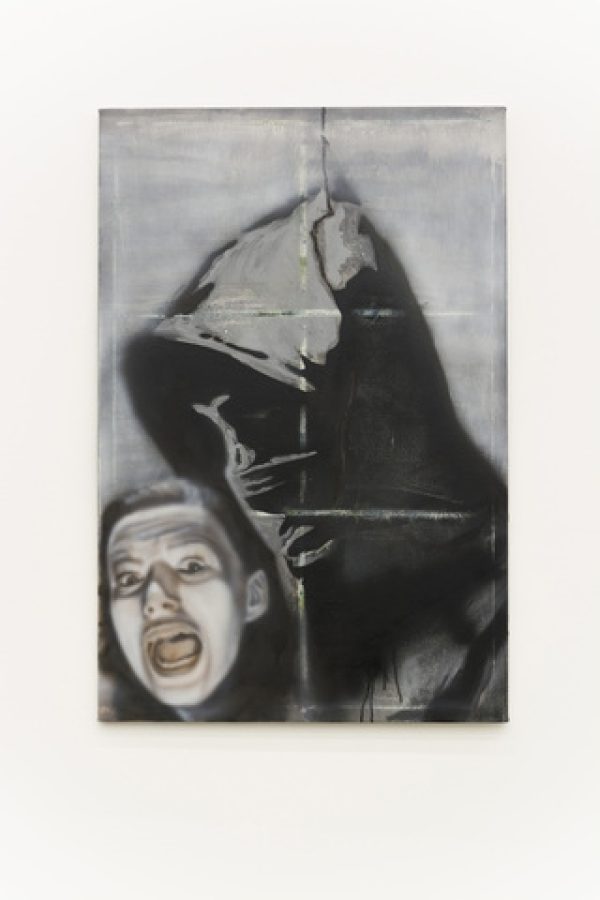

Portrait of a Street Artist, 2, 2015

Acrylic, oil and enamel on canvas

108 x 79 cm

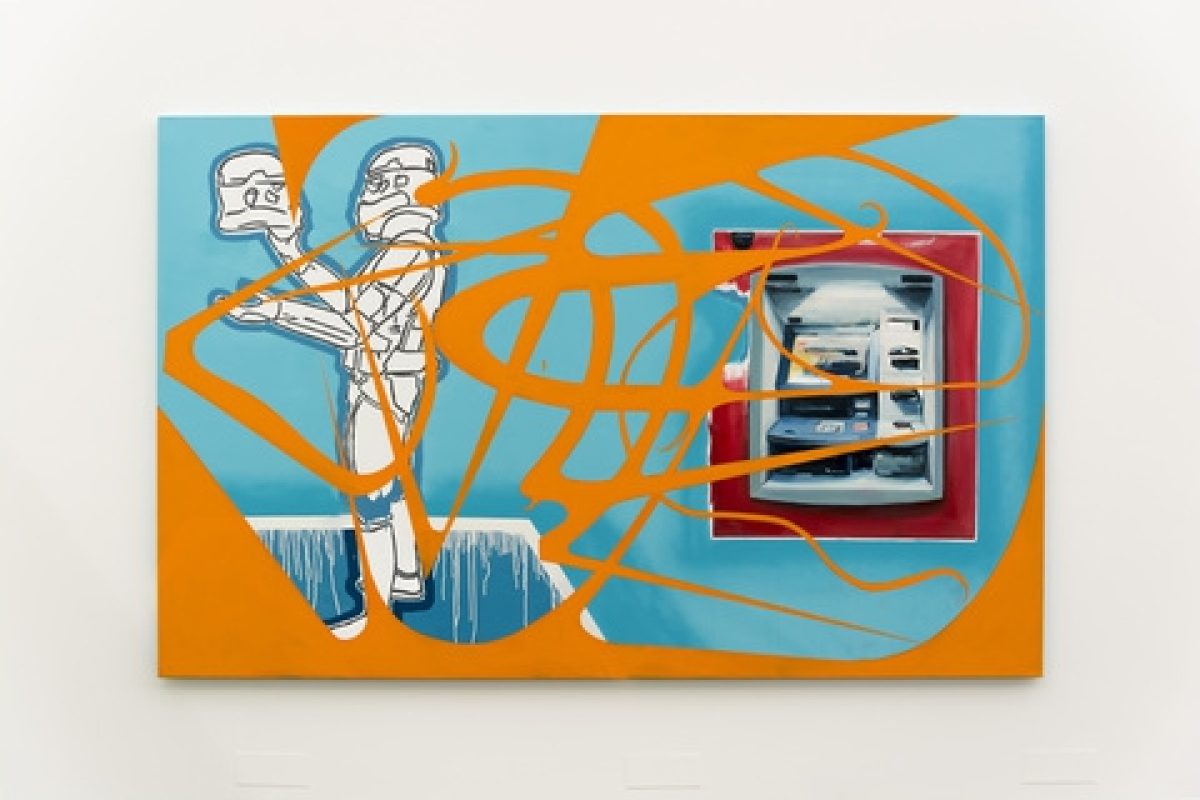

Mirror Man, 2015

Acrylic on canvas

190 x 300 cm

Portrait of Meyne Wyatt / Black Digger (colour version), 2014

Mixed media on canvas

2 panels, 85 x 85 cm each