Kim Guang Nan

The Future is Bright

20th April – 21st May 2016

Anna Schwartz Gallery

The Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) holds deeply to its national name. In the West, it is invariably North Korea. What most people know of its art is a heroic and home-grown reworking of Socialist Realism, the peasant and industrial proletariat in action for the collective good. Not a skerrick of paranoia as the endless advance of ideological triumphalism marches on. Propaganda posters and other media such as sculpture and portraits hold the same line – confident, warmth in homeland collectivism, resistant to other thought and aggressive in defence of those who condemn it. But within this last bastion phenomenon is a complex and subtly varying syntax.

What are we to make of an artist whose work is born out of his imagination, where no apparent role exists other than the artist’s self-expression and fully realised in this exhibition? The role for artists is pre-determined but within this regulated and supervised environment cameos of personal expression appear.

Kim Guang Nan was born in 1953, a few months after the July armistice of the North and South Korean War and trained at Pyongyang Central Art Academy, and having qualified, worked at the Mansudae Art Studio. Established by President Kim Il Sung, it remains the major state-run organisation for artists in North Korea. A physically vast enterprise, artists work across styles and mediums – painters in oil and ink, printmakers, craft workers, designers, sculptors, ceramicists and mosaic artists – handicraft and embroidery is the main activity for women. Propaganda work is ubiquitous from studio work to public art. Any form of abstraction does not exist and is regarded as bourgeois and anti-revolutionary.

Nicholas Bonner lives in Beijing and has become something of a cultural impresario for North Korean artists. As a regular visitor to Mansudae since 1993, he works closely with its artists. He has given them a voice outside North Korea where, if circumstances were left to lumber along, art would remain constrained, predictable, and ideologically single-minded. The ideological imperative for making art tends to override other personal interests and ideas for new projects not being rejected out of hand is a fickle arrangement. Nicholas coordinated North Korea’s participation in the Asia Pacific Triennial, 2009, at Queensland Art Gallery QAGOMA. The Federal government cancelled the artists’ visas at the eleventh hour. He commissioned work for the architecture section of the 2014 Venice Biennale which awarded the Golden Lion to (South) Korea, but included a section from DPRK. ‘Comrade Kim Goes Flying’ was released in 2012, a joint British-Belgian-North Korean romantic comedy feature film and jointly directed by Nicholas Bonner.

It is a necessary reality that he speaks for the artists he works with. In the case of ‘The Future is Bright’ and Kim Guang Nan, it is treated seriously, and not ‘look this is what North Korea thinks the future will be like!’ It began as a project exploring their upbringings, imagining a future with all the trepidation and excitement that was involved. ‘We both clearly remember the graphics we were shown as kids and how we used this information to develop our imagination. There was so little else available so those comic images of rockets and alien life forms were not only massively appealing in their own right, but provided a stimulus to send us on our own imaginative journeys.’

Nicholas had a North Korean storybook with an illustrated front cover and Kim ‘had read the book and found it fun and reminded him of his youth … we would then sit down and discuss the piece in the terms of how it worked visually … colour schemes, keeping it simple and comic like. Both of us recognise our childhood in all of the images … the imagination of a child. … and now as grown men still the feeling of exploration and danger.’ The physical personality of the linocuts was important to convey a feeling which is unmistakably pre-digital which includes deliberate glitches in registration. The high gloss paper was sourced in China, the lino blocks in Pyongyang and the heavy, sticky ink was sourced locally too.

Imbedded within the visual narrative of ‘The Future is Bright’ is a reflection of a utopian vision of North Korea. It is a socialism shaped by the influence of Soviet idealism, where science, exploration and the vastness of its imaginative reach might become part of a proletarian dream(1). The Americans failed with a missile launch in 1957 while the Soviets successfully launched ‘Sputnik’ in the same year and confirmed that the Cold War was a political, scientific, hearts and minds war. In the case of ‘The Future is Bright’ western audiences might read it as an irony about one of the least visited places on the planet. But in reality it’s about the imagination of childhood realised again as an adult, an imagination born out of circumstances where the individual imagination usually remains unseen.

Doug Hall AM

1. For a comprehensive account of the Soviet influence on North Korean art, illustration and literature see Dafna Zur, ‘Let’s Go to the Moon: Science Fiction in the North Korean Children’s Magazine Adong Munhak, 1956−1965’, The Journal of Asian Studies, Available on CJO 2014 doi:10.1017/s0021911813002404

Quotes from Nicholas Bonner to Doug Hall from an email conversation, March, 2016.

Images

Kim Guang Nan

Reflection of rocket, 2015

Linocut on high gloss paper

60 x 70 cm, 78.5 x 88.5 cm framed

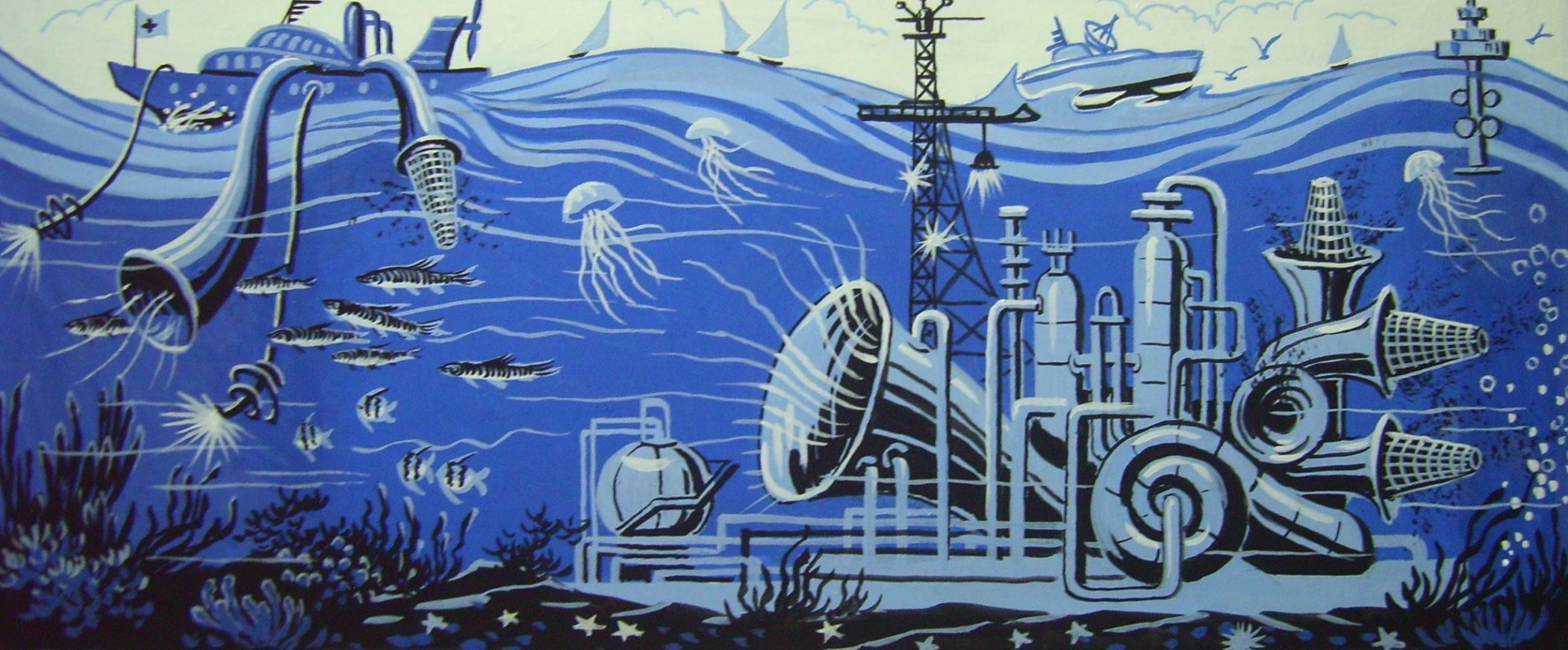

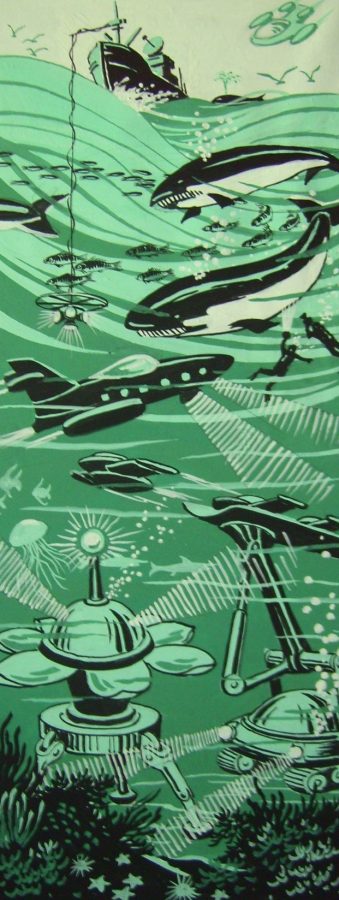

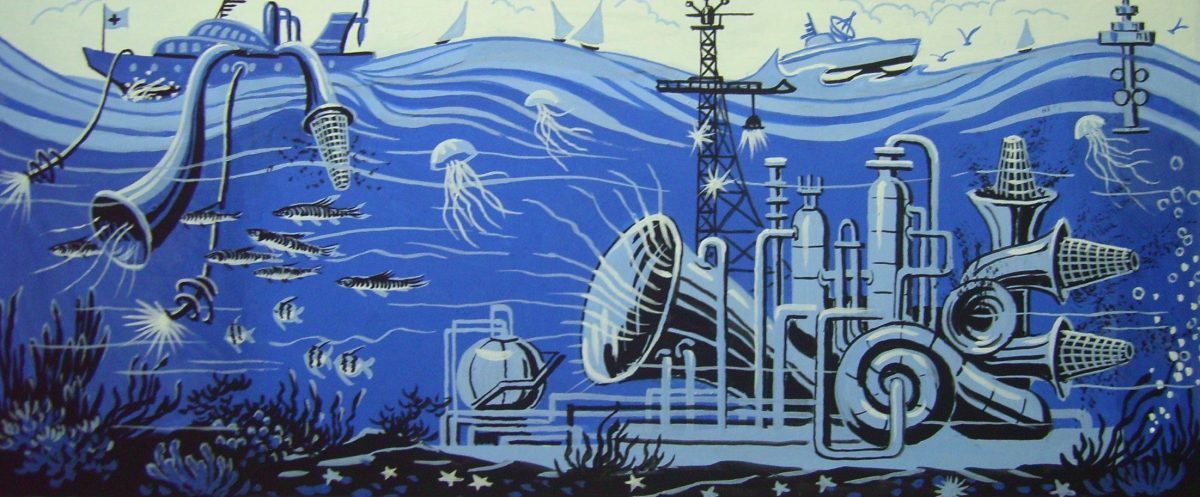

Kim Guang Nan

Underwater research, 2015

Linocut on high gloss paper

99.5 x 40 cm, 118.5 x 58.5 cm framed

Kim Guang Nan

Undersea world, 2015

Linocut on high gloss paper

60 x 70.5 cm, 78 x 89 cm framed

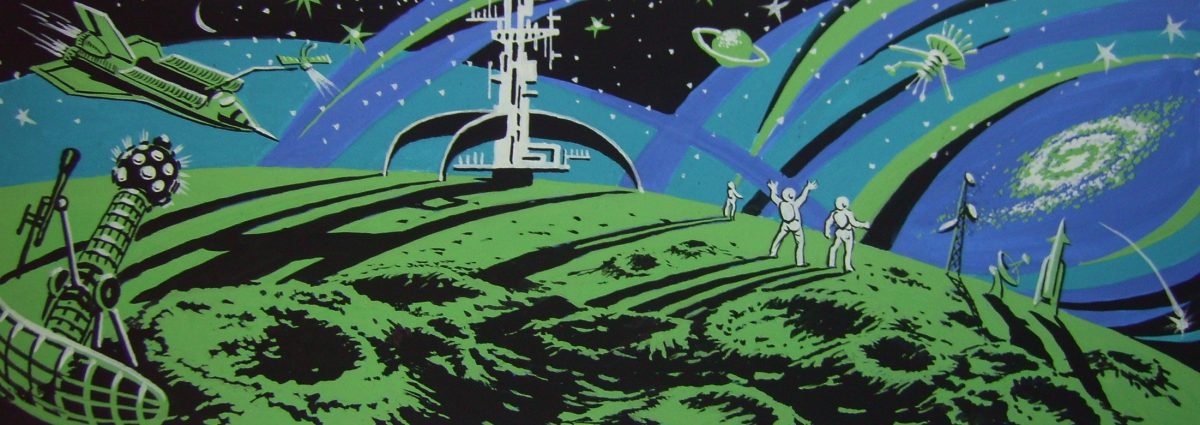

Kim Guang Nan

Space scene, 2015

Linocut on high gloss paper

40 x 100 cm, 58.5 x 118.5 cm framed

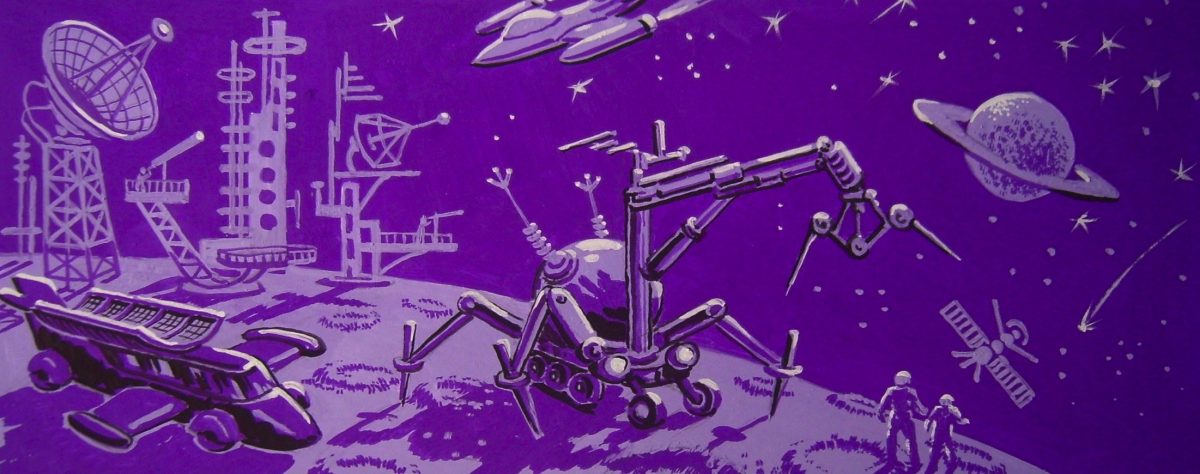

Kim Guang Nan

Planet survey, 2015

Linocut on high gloss paper

39.5 x 99.5 cm, 58.5 x 118 cm framed

Kim Guang Nan

Animals and plants, 2015

Linocut on high gloss paper

40 x 99.5 cm, 58.5 x 118 cm framed

Kim Guang Nan

Rocket fired towards planet, 2015

Linocut on high gloss paper

40.5 x 99.5 cm, 59 x 118 cm framed

Kim Guang Nan

Space man reflected in helmet, 2015

Linocut on high gloss paper

40 x 99.5 cm, 58.5 x 118 cm framed

Kim Guang Nan

Animals, 2015

Linocut on high gloss paper

40 x 100 cm, 58.5 x 118.5 cm framed

Kim Guang Nan

Filtration under the sea, 2015

Linocut on high gloss paper

40 x 100 cm, 58.5 x 118.5 cm framed

Kim Guang Nan

Inside the submarine, 2015

Linocut on high gloss paper

40 x 100 cm, 58.5 x 118.5 cm framed

Kim Guang Nan

Conservation of the sea, 2015

Linocut on high gloss paper

42.5 x 59 cm, 61 x 77.5 cm framed

Kim Guang Nan

Satellite maintenance, 2015

Linocut on high gloss paper

42.5 x 59 cm, 61 x 77.5 cm framed

Kim Guang Nan

Deep space mining, 2015

Linocut on high gloss paper

42.5 x 59 cm, 61 x 77.5 cm framed

Kim Guang Nan

Running low on oxygen, 2015

Linocut on high gloss paper

42.5 x 59 cm, 61 x 77.5 cm framed

Kim Guang Nan

World rescue team, 2015

Linocut on high gloss paper

43 x 60 cm, 61 x 78.5 cm framed

Kim Guang Nan

Local space transport, 2015

Linocut on high gloss paper

42 x 59 cm, 61 x 77.5 cm framed