Stieg Persson

The Fragonard Room

3rd July – 9th August 2014

Anna Schwartz Gallery

Stieg Persson’s paintings in ‘The Fragonard Room’ suggest a shift in contemporary hierarchies of culture, and “taste” as an identifying factor of class.

Jean-Honoré Fragonard, whose works in the Frick collection (spurned by Louis XV’s mistress, the Comtess du Barry, for whom they were commissioned at the height of the artist’s vogue), has come to be synonymous with the maligned period of Rococo, French painting of the pre-revolution aristocracy. Works by Rococo’s masters have continued to be seen as kitsch, decadent, effete and in bad taste; a trend that ended with the execution or exile of its patrons. It is little recalled that Fragonard himself was protected from the same fate by one of the revolution’s greatest artists, Jacques-Louis David – one of the master’s own protégés.

The varied and complex history of the moment of Rococo, mirrored in the convoluted story of the paintings that came to give Frick’s Fragonard Room its defining features, are re-deployed by Persson in a series of works that investigate contemporary parallels in changes of taste and the desire for decadence as a political and social drive.

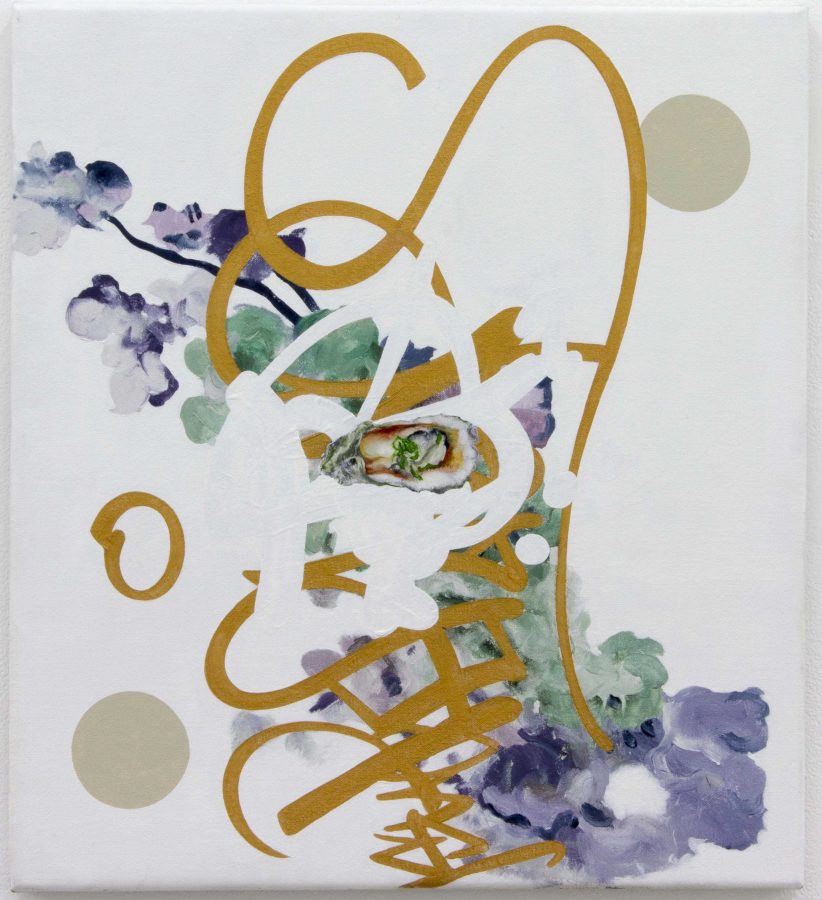

Elements of the grammar of Rococo are adopted by Persson as a means to address the social currency of luxury, particularly the growth in popular esteem of high-end cuisine. Taken as a critique of the contemporary obsession with food, these works trace a looped and tangled picture of food’s rise in social consciousness into a more general understanding of how ‘taste’ is acquired, and by whom. As contemporary society places greater significance on the connoisseurship of eating, it does so in lieu of engagement with culture as it is traditionally conceived: music, theatre, literature and art.

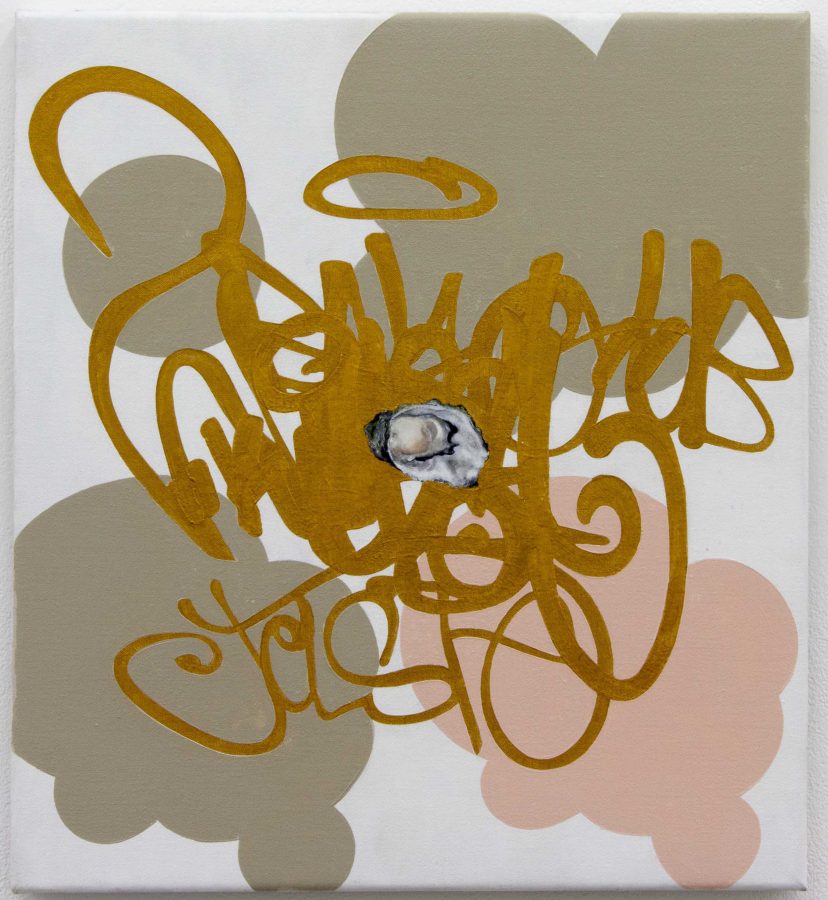

Persson’s works, splicing varied registers of painting together as if by collage, present the objects of current foodie affection on top of quotations of Rococo painting and gilded tagging that the artist has noticed around Melbourne’s south-eastern suburbs. Vignettes of landscape after Fragonard, Watteau and Boucher are positioned behind the specialties of Monarch Cakes in St Kilda, conflating two ‘institutions’ of visual and gustatory delight. A Monkey eating Quinoa recalls the singerie fashion of including anthropomorphised primates in decorative and fine art, as well as to the origins of the ‘superfoods’ sold in the often-oblivious West. Oysters on the half-shell are emblematic of Rococo, whose very name derives from rocaille, fanciful artificial shell or rock gardens.

Persson’s use of ‘found’ tagging from the city’s wealthy areas is again a provocation to discussion of Australia’s discomfort with its own non-classless society: these forms are appropriated from what are likely to be the narcissistic pursuits of well-to-do ‘delinquents’. But it is important to distinguish the particular type of class that is formulated here: not one that is based on wealth, but rather on taste. Such taste is further conditioned by generation, and location; Melbourne being a city that celebrates street art as much as it does food.

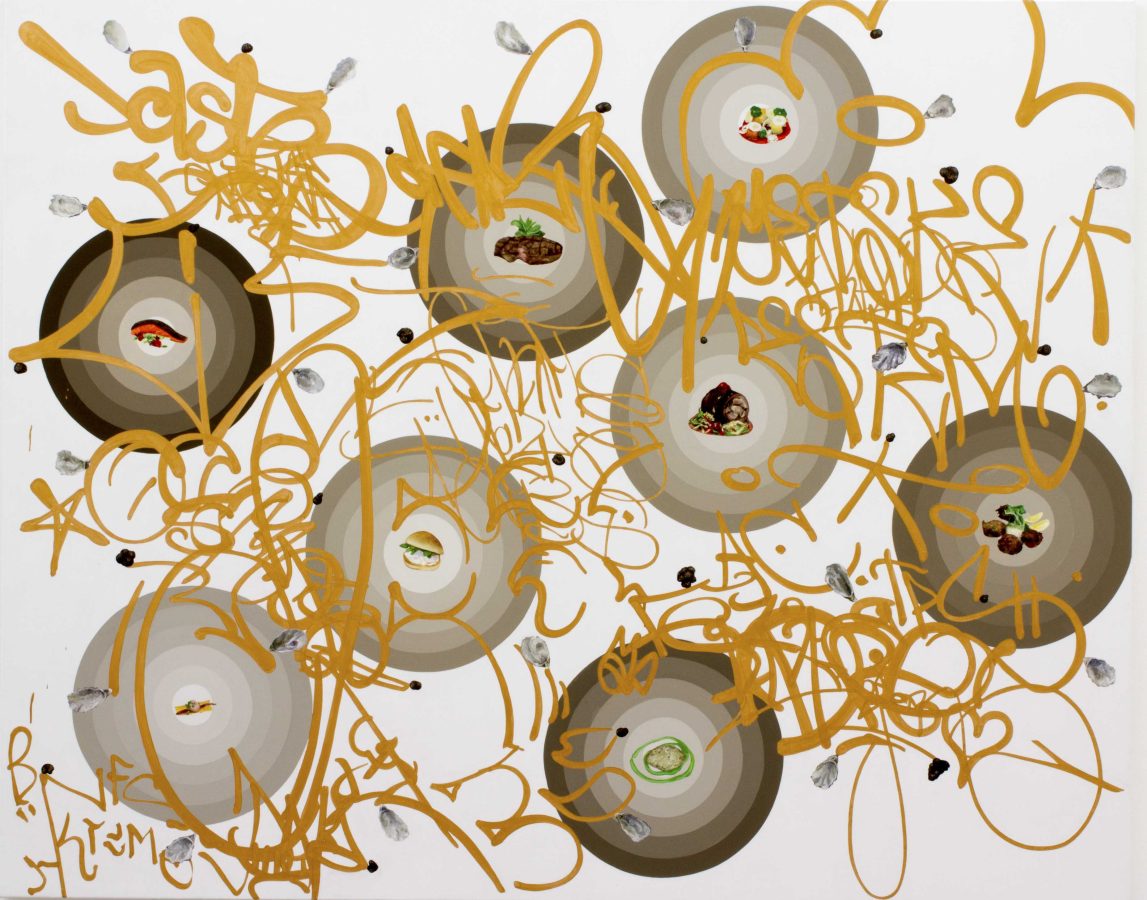

If the ornate Rococo gestures and shapes were thrown out in favour of austere, democratic and morally upright Neo-classical bourgeois values, contemporary food culture shows a slide in the opposite direction: the conventional feedback loop of low aesthetic taken up by the elite is reversed by the trend of the middle-class mass aping the food-based rituals of the upper class. Through reality TV franchises and artisanal local everything, the disposable luxury of fine food has become the priority for Australians’ disposable income. Persson’s satire may take cues from the prints of Hogarth or George Cruickshank, but not without some self-reflection on complicity: in Signature Dishes, Persson paints in miniature the dishes that have made local chefs famous (Golden Fields’ New England lobster roll; Tetsuya’s confit of ocean trout) – all dishes that the artist has eaten himself.

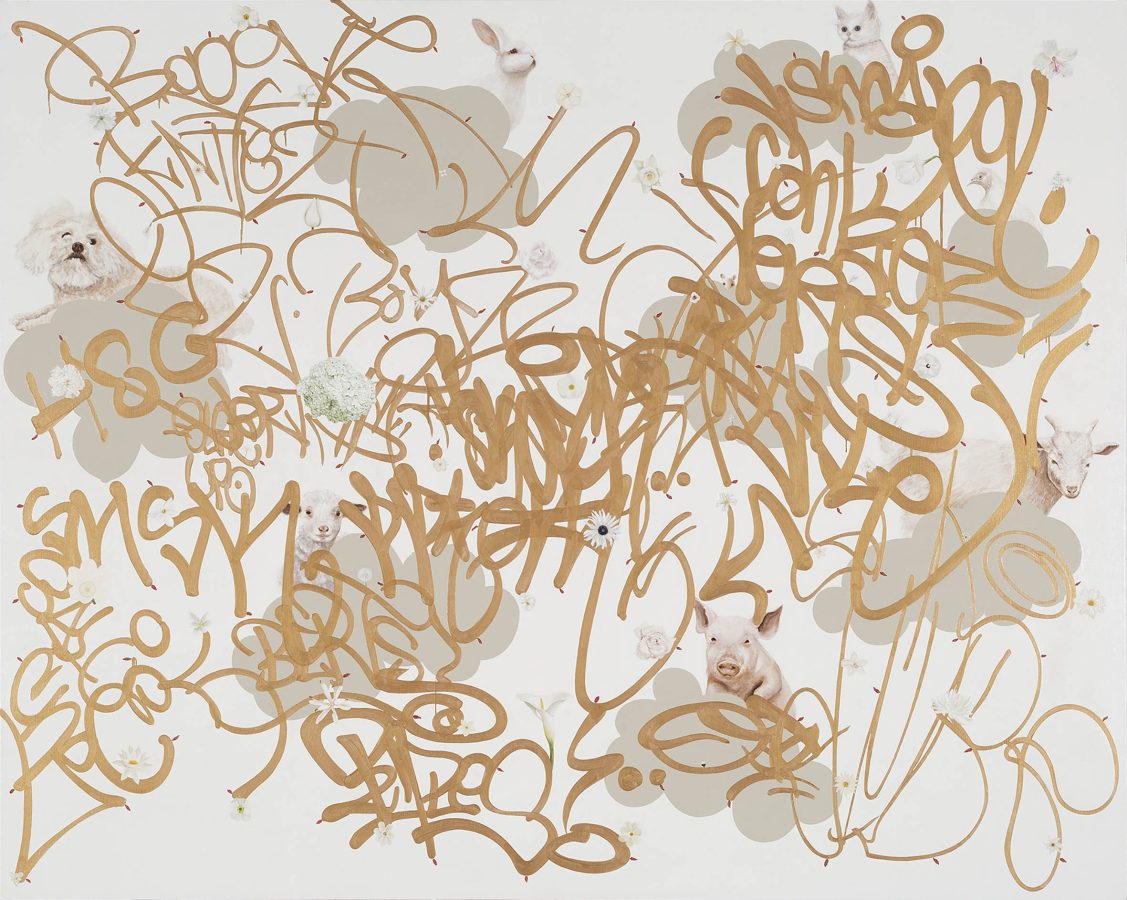

The singular experience of sensation (of flavour or otherwise) is at the core of Rococo’s emphasis on touch, and on the visualisation of touch in art. In Persson’s works, sensation is made visible in the concentric circles of gradated colour that push single coffee beans and macarons toward the viewer, out of the surface of the canvas. These geometric motifs, recalling radical movements in European Pop art of the 60s, crash into cartoon cloud-forms in sugary tones that could be Pop, or 19th-Century hand-coloured etchings, or Pierre Hermé branding. But clouds return these works to the realm of Rococo, whose obsession with touch was matched only for an insistent demand for the sky, with characters thrown into the air with complete disregard for gravity, despite slavish devotion to surface texture.

If Rococo taste defied the laws of physics for the sake of sensation, today’s pleasure in luxury appears to defy the laws of economics. The conventional understanding of luxury being tied to exclusivity is no longer valid; conspicuous consumption driving the market for industrially-produced McCafé macarons. And as molecular gastronomy has become an experiential ‘art form’ available only to the wealthiest, art itself has remained democratic and freely accessible, for those who remember it.

Images

Stieg Persson

Altocumulus, 2014

oil on linen

153 x 127 cm

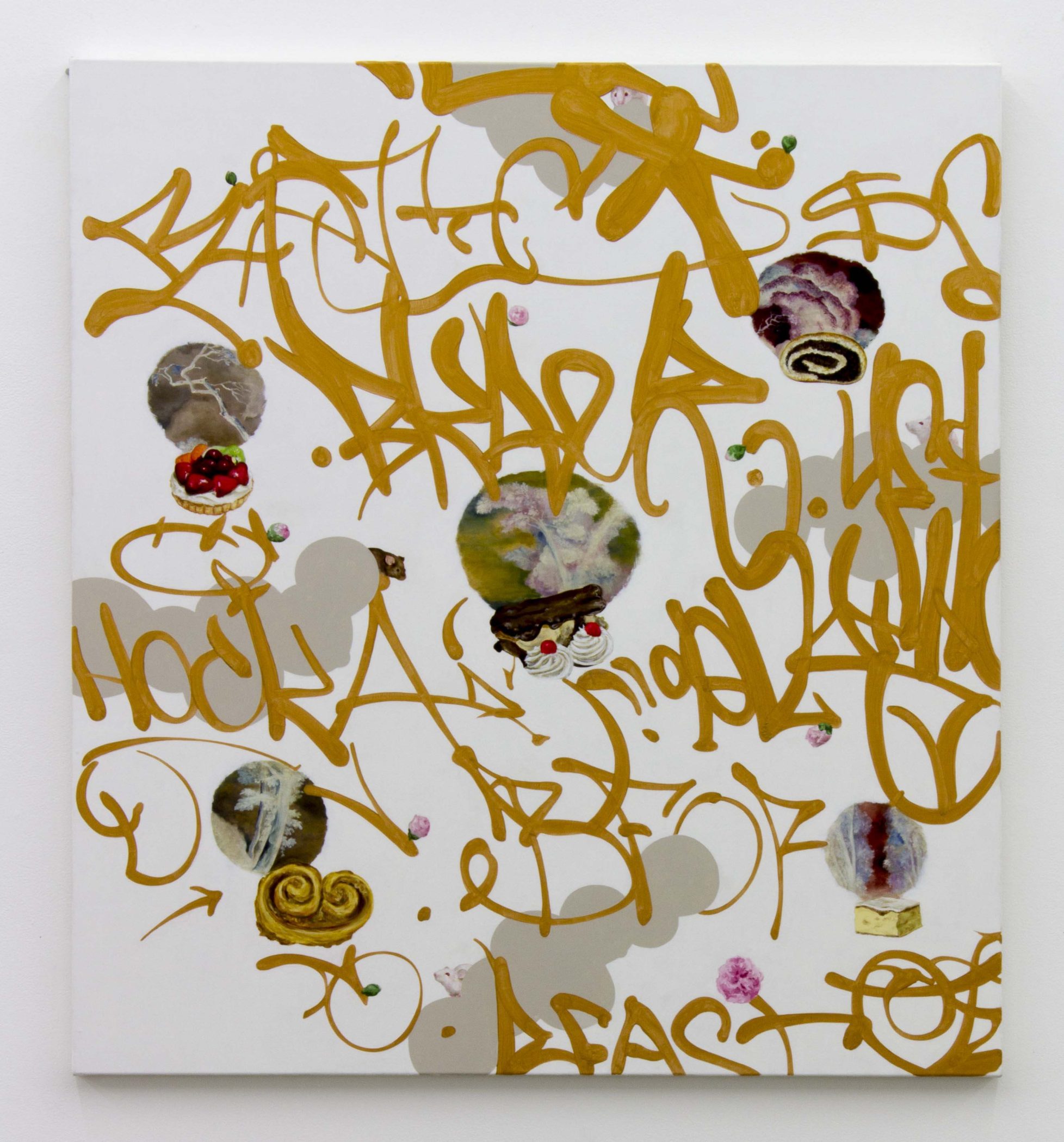

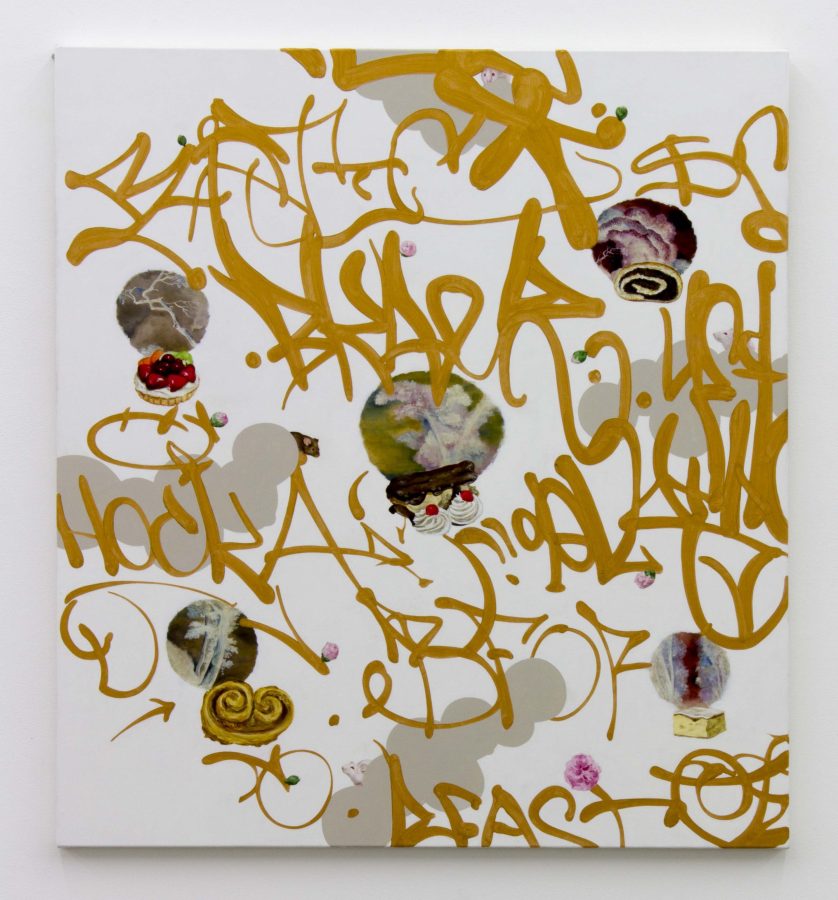

Stieg Persson

Monarch Cakes, 2014

Oil on linen

122 x 112 cm

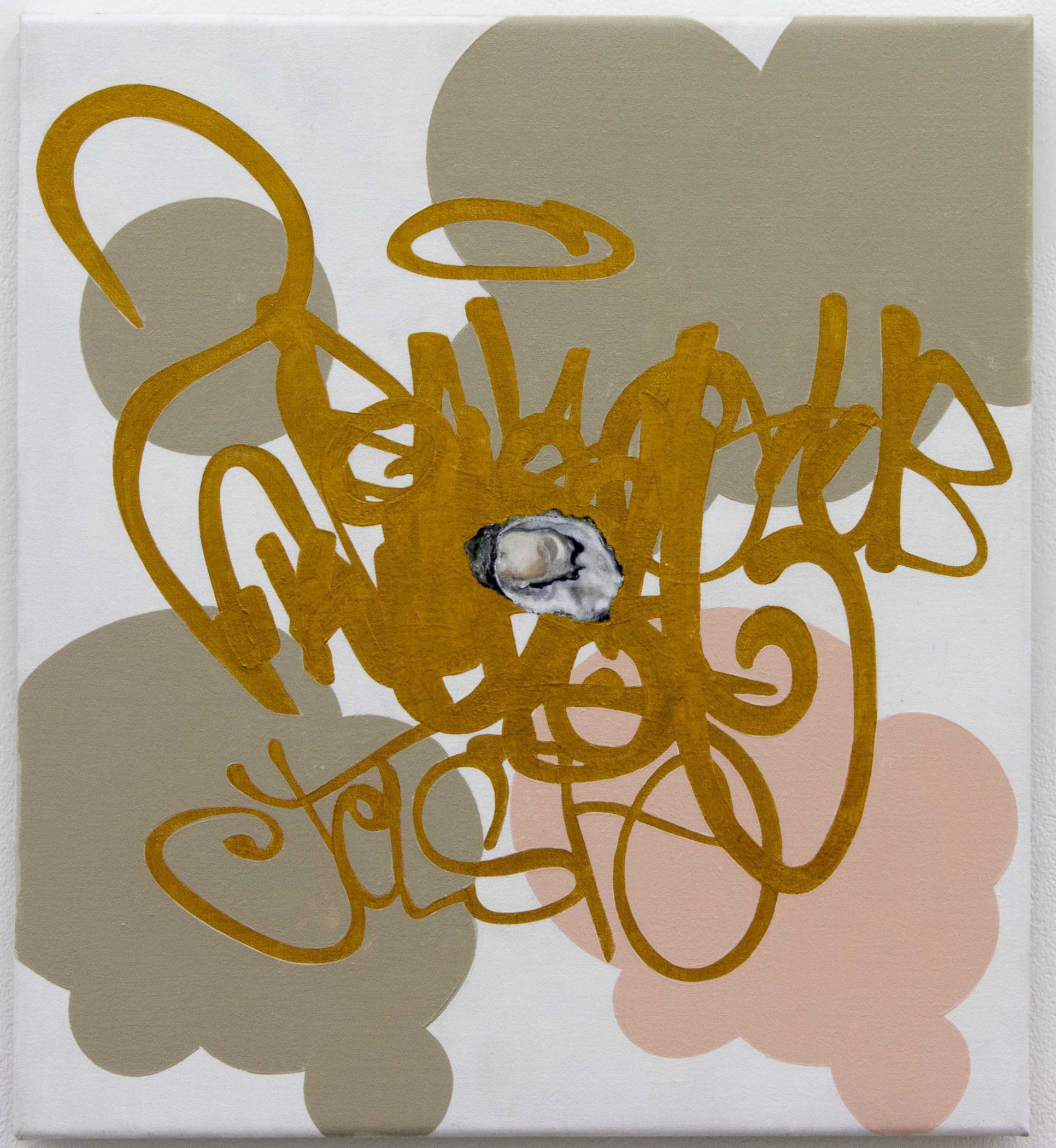

Stieg Persson

Au naturel, 2013

Oil on linen

52 x 46 cm

Stieg Persson

Ethiopian Sidamo and macarons, 2014

oil on linen

112 x 112 cm

Stieg Persson

Asian Style, 2013

Oil on linen

52 x 46 cm

Stieg Persson

Cumulus, 2013

oil on linen

153 x 127 cm

Stieg Persson

Philosophy of Individualism with Goji Berries, 2013

oil on linen

187 x 227 cm

Photo: Christian Capurro

Stieg Persson

Aromatherapy, 2013

oil on linen

122 x 122 cm

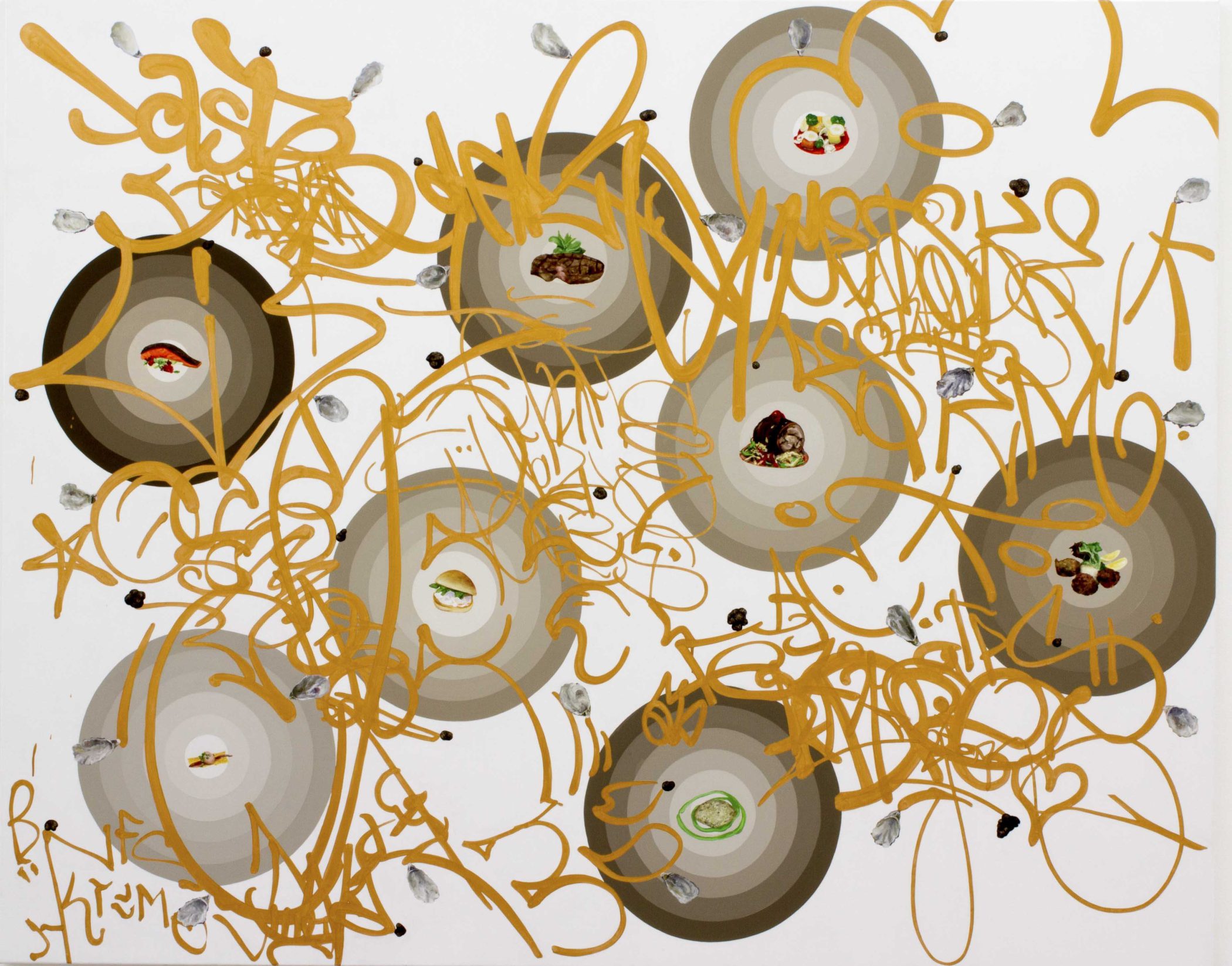

Stieg Persson

Signature Dishes, 2014

Oil on linen

183 x 229 cm