remapping

22nd August – 29th September 2012

Anna Schwartz Gallery Carriageworks

Daniel Crooks’ ‘remapping’ suggests views of other possible worlds. In video and photography, Crooks records, dissects, and reconfigures sections of lived reality.

Cloud Atlas (fitzroy 1:23) traces the transient, intangible material of the sky. Borrowing the title from David Mitchell’s Booker Prize-nominated novel, the artist attempts to chart physical space by travelling a pre-determined path on the ground by car. Our point-of-view is destabilised by the simple manipulation of the camera shooting directly up, into the sky. Unable to navigate by the roads or street signs, we can only track the artist’s movement by landmarks in the air – bare trees, the roofs of buildings, electricity cables and the recognisable Victorian tower of the Fitzroy Town Hall. Reflecting our attempts to describe and navigate the world with rigid systems, Crooks reminds us that our own realities are constituted through perception.

In Pan No.10 (neither here nor there), the artist links discontinuous locations and temporalities into an alternative whole. A further development from the investigations of his work A Garden of Parallel Paths, which was commissioned for the 2012 Adelaide Biennial, this work sees disparate spaces colliding at right-angles, creating a series of virtual cross-roads where people and moving objects intersect, merge momentarily, and disappear. As the ‘real’ space of the video becomes increasingly fractured over time, the glitches and blurred edges become sites of possibility and intrigue. Like the edges of clouds, matter disperses across space and hints at dimensions other than those perceived to be real.

The materiality of time constantly asserts itself in Daniel Crooks’ videos, and in Train No.10 (onward backwards) the artist returns to the vehicle which has so often been evoked to describe consciousness, linear time, and relativity. Utilising a Tokyo monorail as a large-scale tracking device for his camera, Crooks again blurs the distinction between time and space, displacing the ‘place’ of a small section of footage so that it appears to occur as a thread of duration. Drawing on the intertwined cultural histories of cinema and locomotion, Crooks places the viewer inside motion, recalling the Lumière brothers’ L’Arrivée d’un Train en Gare de la Ciotat.

Elsewhere in Tokyo, Static No.19 (shibuya rorschach) is located in the street, where the frenetic life of the intense city moves with a unusually delayed and graceful motion. Standing still, a single drifter presents himself to Crooks and the camera rig. Despite his apparent acknowledgement of the crowd rushing past, he remains separate, capturing the artist by staying as static as the camera. This sole protagonist is socially isolated, but here appears to stake out his own location in time; the footage is slowed to a pace at which he alone moves and sees.

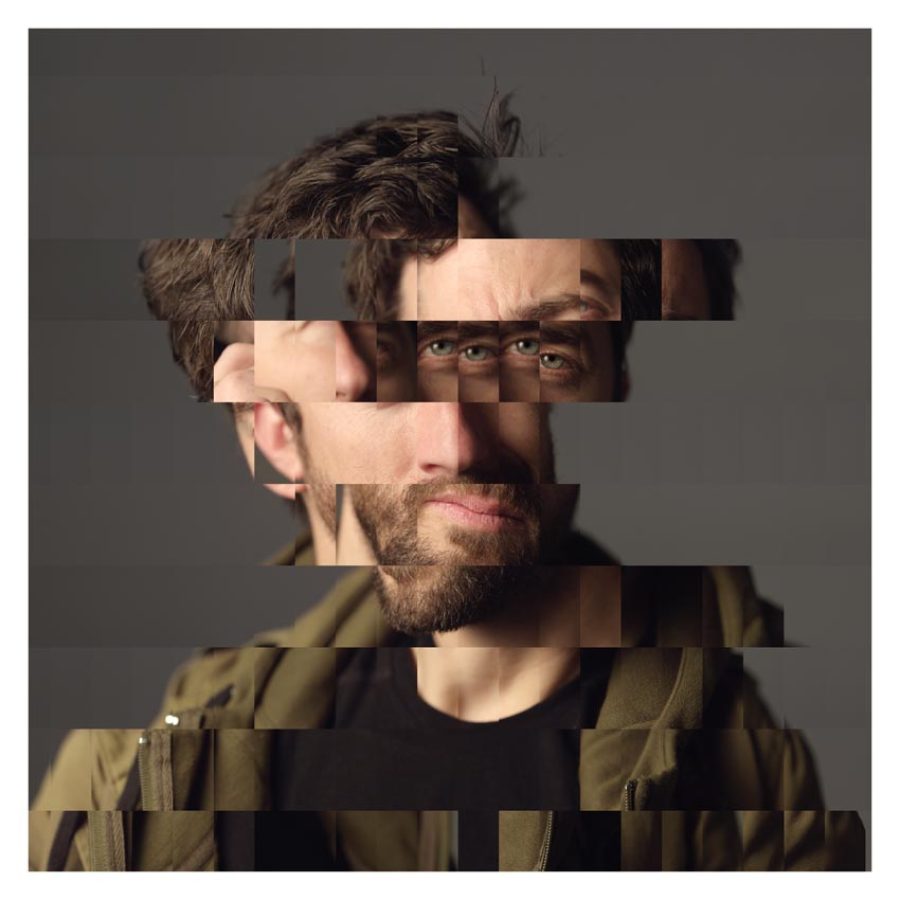

The Portrait series of photographs articulates the artist’s interest in a temporal rather than a physical image of life. Each work is the study of a single person over a period of about twenty minutes. The video camera is mounted on a ‘robot’ which follows a Hamiltonian path similar to that followed by the artist in Cloud Atlas. It moves around the preset frame of the shot, travelling along a line which draws the vertices of a graph, visiting every point on the graph once only. The camera follows this line, beginning at one point and ending at another, and never crosses a point twice. Reminiscent of Chuck Close’s gridded self-portraits, as well as the surveillance and monitoring technology used in retina scanning, these works do not enter into the personality or ‘essence’ of their subjects, rather, they express the inability of the photographic image to provide a comprehensive, indisputable version of the world. They are both temporal and physical portraits, an indexical trace of the time the artist spent with the subject.

The result of Daniel Crook’s continued fascination with the physical properties of time, ‘remapping’ is imbued with the rigour of mathematics and the gentle metaphysics of photography and the moving image. Remaining salient is the ‘concrete’ material of these ethereal, destabilising works: all that we view has actually occurred, and was simply documented by the artist. Nothing is cut or removed, only displaced in the sequence of time, enough to now offer a view from the wings of a usually assumed reality.

Images

remapping, 2012

installation view, Anna Schwartz Gallery, Carriageworks

remapping, 2012

installation view, Anna Schwartz Gallery, Carriageworks

A Single Path, A Single Past, 2012

Inkjet print on photographic paper

130 x 130 cm (framed)

Cloud Atlas (Fitzroy 1:23), 2012

single-channel High Definition digital video, 16:9, colour, silent

21 minutes

Edition of 3

Train No.10 (onward backwards), 2012

Single channel High Definition digital video, 16:9, colour, sound

7 minutes 20 seconds

Pan No.10 (neither here nor there), 2012

Single channel High Definition digital video, 16:9, colour, sound

8 minutes

Static No.19 (shibuya rorschach), 2012

Single channel High Definition digital video; 16:9, colour, sound

6 minutes 3 seconds

Portrait #23 (self), 2012

Lambda photographic print

400 x 400 cm

Portrait #10 (Tom), 2012

Lambda photographic print

130 x 130 cm

Edition of 3

Portrait #13 (Tessa), 2012

Lambda photographic print

130 x 130 cm

Edition of 3

Portrait #14 (Chris), 2012

Lambda photographic print

130 x 130 cm

Edition of 3

Portrait #8 (Andy), 2012

Lambda photographic print

130 x 130 cm

Edition of 3

Portrait #11 (Hannah), 2012

Lambda photographic paper

130 x 130 cm

Portrait #9 (Takeshi), 2012

Lambda photographic print

130 x 130 cm

Edition of 3

Portrait #12 (Jasmin), 2012

Lambda photographic print

130 x 130 cm

Edition of 3