Kathy Temin

Pet Cemetery

2nd October – 8th November 2014

Anna Schwartz Gallery

In Kathy Temin’s recent Monument thickets of large, stuffed synthetic fur tree sculptures have been transplanted into gallery spaces, forming snowy white, neatly topiaried rows or imposing, impenetrable black forests. To view these works it is necessary to negotiate a path, to navigate through an environment, and to acknowledge the scale of the body against the mass of materials. Their immense size and density recalls the threat of the forest, but their perfectly composed orderliness speaks more of the formal garden. Nature, the wilderness, the unknowable; and culture, sociability, the known — Temin’s work is structured around the possible states between apparent binaries.

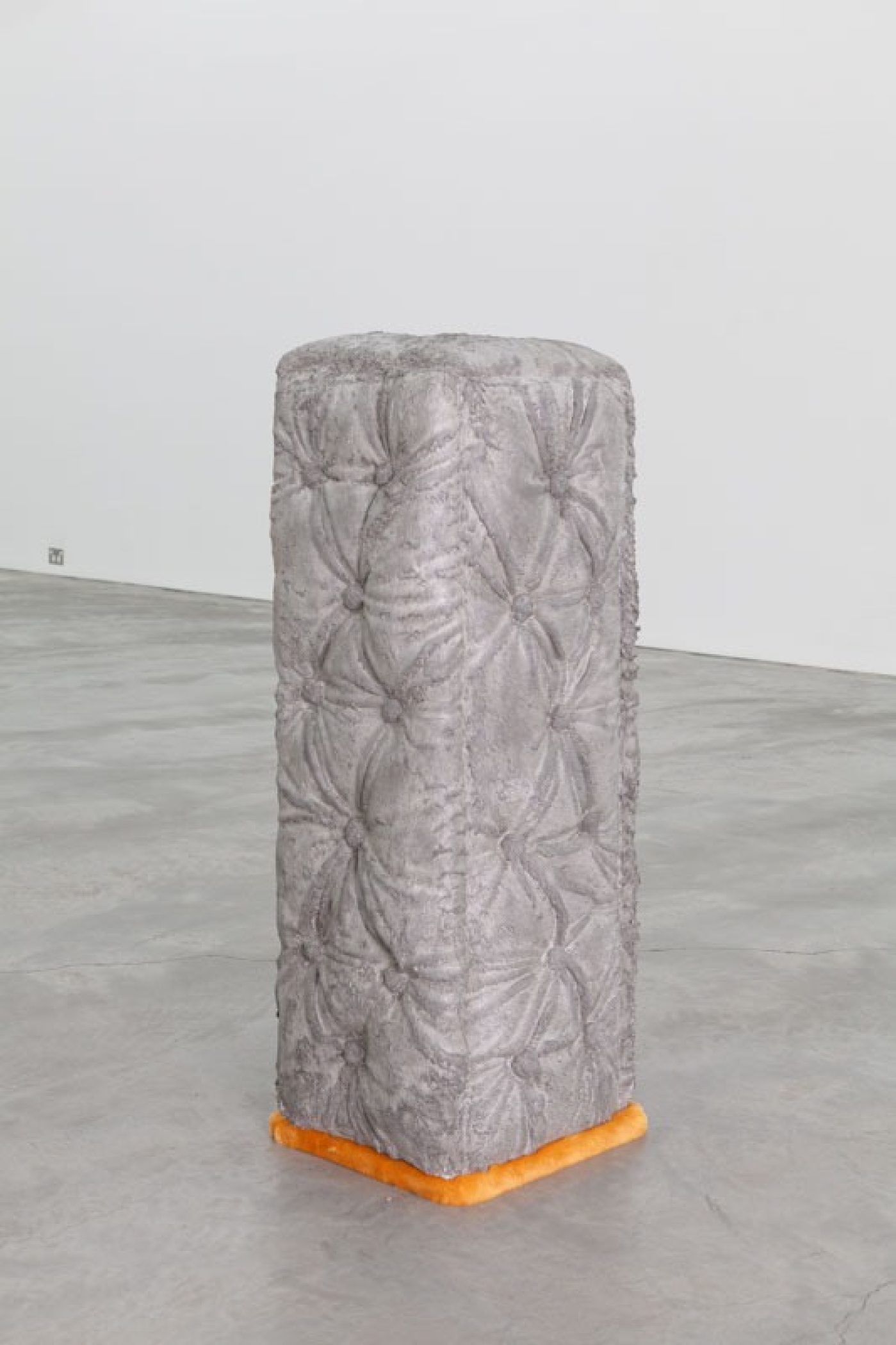

‘Pet Cemetery’ retains elements of the garden, though reduced in scale to something more like interior decoration, pot plants or front-yard topiary. The forest has become domesticated. Nine sculptures, comparable in size to items of household furniture, such as the sideboard, invoke references to interior design from the 1970s. They invite individual inspection and require a particular kind of journey through the gallery. The works are concrete and MDF, solid and heavy, but softened with Temin’s signature synthetic fur upholstery, here the colour is dark orange, filled with synthetic stuffing and finished in the Chesterfield style, like grand old leather couches. These luxuriant mini-monuments are proposals for tombs or coffins for pets.

Particular animals are remembered in the titles such as Pet Tomb: Tina, Pet Tomb: Ebaneza, and Pet Tomb: Harry. The kind of animal remembered by each tomb — their species, their personality, their relationships — cannot be ascertained for certain (they are (the “human”) names of the artist’s and her friends’ deceased pets. That such animals are valued by people is what is clear in Temin’s proposals. One’s introduction to loss is often through the death of a pet. The rituals that surround the deaths of domesticated animals are reminders of the revealing place they hold in human social life: they are ‘part of the family’, reared and trained in the home, often loved and sometimes loving — at least, their emotional lives are so conceived by people. Temin’s work has frequently occupied territory where objects are transformed or translated, impersonated or performed. Anthropomorphism — both studied in others, and employed as a strategy — is something she uses to reflect and describe the strange norms of human behaviour.

In ‘Pet Cemetery’ Temin applies to the animal world certain privileges and tributes that are reserved for human rituals around death and commemoration. The spirit of luxuriance and excess, devoted to beings no longer able to appreciate such gestures, is something that Temin has looked at in various religious traditions, especially since travelling through Eastern Europe and Italy in recent years. The grandiose Catholic churches of Venice and elaborate Jewish family tombs in Hungary; never visible to those whom they were built to honour. Temin is interested in homage, and how remembrance is made; in Pet Cemetery, perhaps she asks who, indeed, the tribute is really for.

Temin’s work unabashedly encompasses contradictions and equivocations: the monumental and the domestic; the regal and the homely; the deadpan-genuine and the possibly-ironic. She adapts certain traditions to accept what they were built to exclude, and in ‘Pet Cemetery’, there lingers the desire within her earlier work to allow the body back into abstraction, despite Modernist art’s efforts to repress it. In Temin’s work, the monochrome is the nexus of a plurality of experience and association. Her monuments, being both minimal and sentimental, are petitions against exclusion and forgetting.

Images

Kathy Temin

Pet Cemetery, 2014

installation view, Anna Schwartz Gallery

Kathy Temin

Pet Tomb: Harry, 2014

concrete and synthetic fur

84 x 86 x 36 cm

Kathy Temin

Pet Tomb: Oscar, 2014

concrete, MDF and synthetic fur

242 x 48 x 39 cm

Kathy Temin

Pet Tomb: Tina, 2014

synthetic fur, MDF and filling

178 x 100 x 110 cm

Kathy Temin

Pet Tomb: Roger, 2014

synthetic fur, MDF and filling

109 x 210 x 50 cm

Kathy Temin

Pet Tomb: Csilla, 2014

concrete, MDF and synthetic fur

110 x 34 x 38 cm

Kathy Temin

Pet Tomb: Ebeneza, 2014

synthetic fur, MDF and filling

220 x 95 x 95 cm

Kathy Temin

Pet Tomb: Nikki, 2014

synthetic fur and MDF

108 x 60 x 65 cm

Kathy Temin

Pet Tomb: Boris, 2014

concrete, synthetic fur, MDF and filling

129 x 34 x 34 cm