Rose Nolan

Performance Architecture

16th May – 6th July 2013

Anna Schwartz Gallery

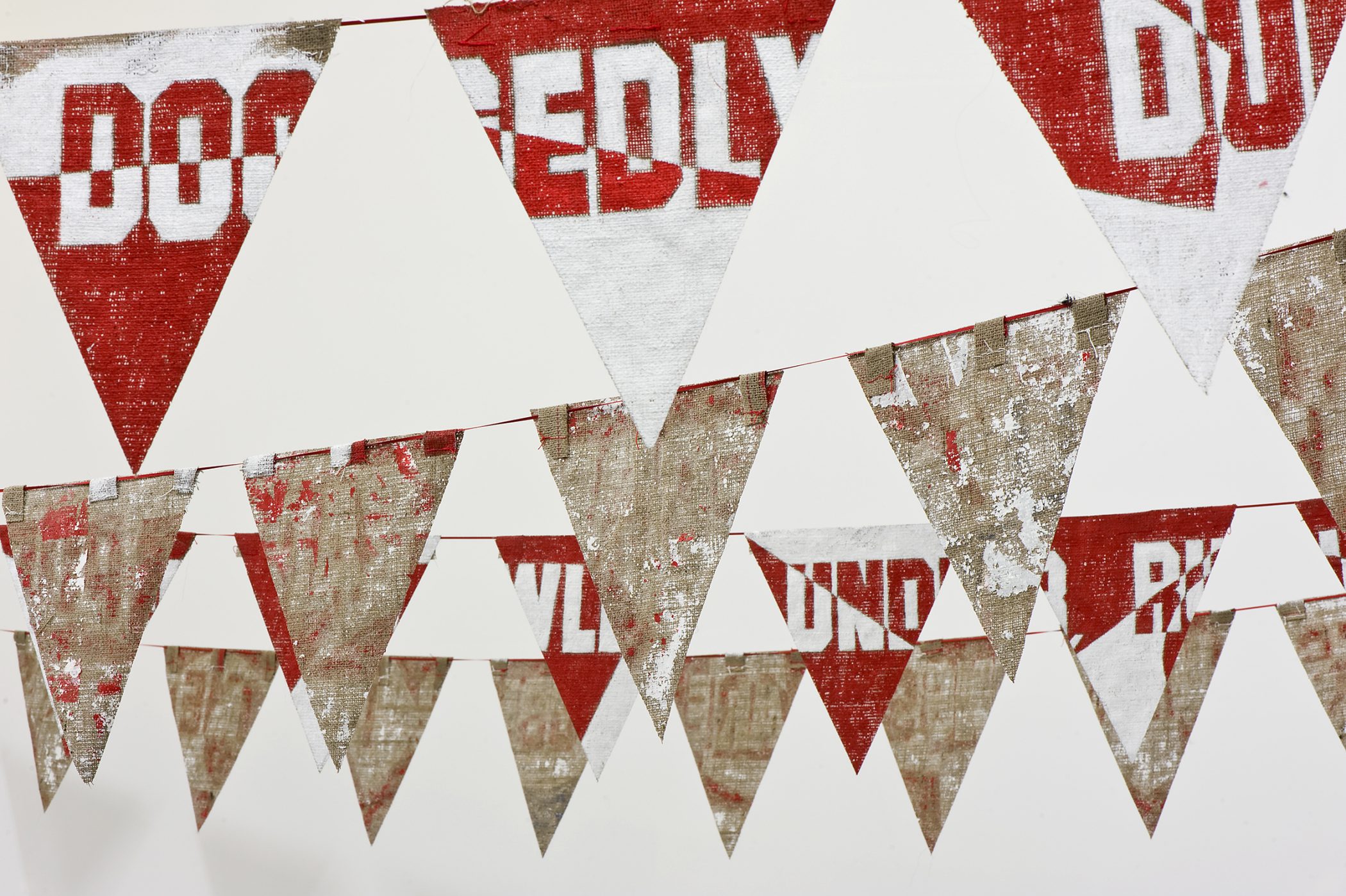

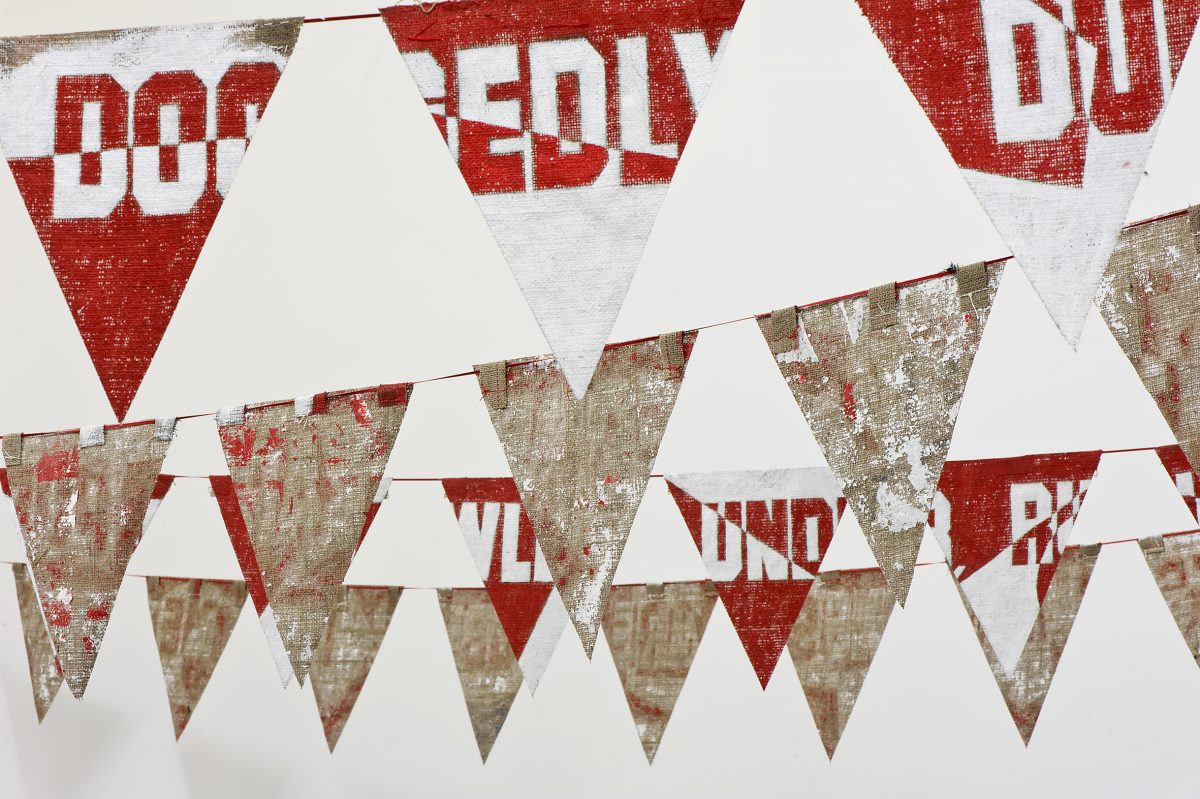

How should one approach Rose Nolan’s exhibition ‘Performance Architecture’? Often making work for floors and walls, Nolan here addresses the ceiling, suspending more than 280 handcrafted pennants across the lateral walls of the gallery — a mini-Michelangelo. Viewed from a distance, the effect of this new work, titled Big Words (Not Mine) — Read the words “public space”…, is akin to the proliferating units of her earlier Flat Flower Work. And whilst the dense massing of flags suggests an autumnal-hued arbor, this time created from painted hessian, the work doesn’t quite mimic vegetation. The pennants are uniformly strung, enabling a lengthy text to be sequenced along their sizeable 100-meter extension. The text is drawn from a 1995 lecture entitled Public Space in a Private Time by Vito Acconci, the American artist turned architect and landscape designer. Passionately voicing the right to non-commercial communal space, Acconci’s text is admirable, but also in places baffling and rant-like. In this sense, it’s not so remote from the delirious and provocative performance and video works of the 1970s that he is best known for. The extracted text exhorts us to “Read the words public space literally, doggedly, dumbly”, and continues with an ambitious three-part definition of what makes public space public. Acconci then proposes that “the space becomes an occasion for discussion, which might become an argument, which might become a revolution”.

Nolan’s work has repeatedly employed pithy statements and single words drawn from vernacular use, but she has also utilised “found” texts from sources as diverse as Sol LeWitt and advertising. Words are always a provocation in Nolan’s work. They should never be taken for granted. Through incessant repetition, Neo-Cubist rupturing, ungainly scale (both big and small), and competing positive/negative forms, Nolan has sought ways to shift language from something familiar to something strange. Acconci’s text is possibly the longest series of words she has employed in a single work, and she obliges the viewer who wishes to read it in full, to mirror its zigzagging route though the gallery at some discomfort to the neck. But isn’t that what looking is all about – hard work? Owing to the triangular shape of the pennants, only the upper half of Acconci’s text is fully legible. Enough remains to get a sense of the text, but the brain needs to struggle to make this happen. But does any of this matter? We appreciate the beauty of Japanese or Arabic lettering without comprehending the actual language they signify. Nolan assists this alternate reading in Big Words (Not Mine) — Read the words “public space”… by using a subtle geometric patterning which overlays the words, emphasising their decorative qualities. Further patterning is revealed on the reverse of the flags, half of which are always in view. Splodges of red and white colour leach through the rough fabric to create small, informal abstract compositions that provide a striking contrast to the fully painted sides.

In what sense does a dense massing of flags constitute architecture, let alone one that is performed? Although the title of Nolan’s exhibition is not drawn from Acconci, it’s clearly associated with a similar nexus of issues involving public space and the role of architecture found in his lecture. Flags, banners and bunting have historically contributed to temporary architectural manifestations, especially heraldic and festive ones. These events almost always involve large crowds, and strings of flags are used to demarcate the large spaces required to contain them. As with military standards, strung flags become rallying points. They also transform spaces for an alternate function by theatricalising them – Swanston Street becomes the setting for a Moomba parade. This is a ubiquitous feature of contemporary political and sporting events, but also many commercial spaces, be they shopping malls, car saleyards, and on occasion, art galleries. All are sites of performance, of actors and audiences. The degree to which these spaces are made public may at best be provisional or illusory, and that is exactly what Nolan’s project problematises here.

Leon Battista Alberti, the Italian Renaissance polymath, codified humanist architectural practice in his 1485 treatise De re aedificatoria. Following ancient Roman examples, he advocates written inscriptions as being the most appropriate and dignified ornament for public buildings. Nolan’s use of Acconci’s text for ‘Performance Architecture’ must be one of the few instances of an architectural inscription, however lowly its actual format, that directly addresses the issue of public space whilst at the same time ornamenting it.

Might Nolan now also acquire Alberti’s personal motto, Quid tum? — What next?

Michael Graf, Melbourne April 2013

Images

Rose Nolan

Big Words (Not Mine) – Read the words “public space”…, 2013

Hessian, acrylic paint, haberdashery thread

Dimensions variable

Installation view, Anna Schwartz Gallery

Photo: John Brash

Rose Nolan

Big Words (Not Mine) – Read the words “public space”…, 2013

Hessian, acrylic paint, haberdashery thread

Dimensions variable

Installation view, Anna Schwartz Gallery

Photo: John Brash