Stieg Persson

Old Europe

19th November – 28th December 2008

Anna Schwartz Gallery Carriageworks

We live in an era where there is no single, persuasive theory of painting. The pluralism of the postmodernist landscape has produced its own orthodoxies, but still there is no mainstream, no Lonely Planet guide. In some ways there could be seen to be an absence of purpose in contemporary painting.

Popular culture, once the inspiration of artists from Warhol to Koons, now exerts an increasingly tyrannical influence on art practice, and the art industry. At the crux of this condition is the ascendancy of a contemporary art that subliminally mimics neoliberal economics to its very core.

The postwar corporate and industrial culture of the United States is central to the understanding of the art of Stella and Warhol; their clear desire to be at one with their times was manifest not only in their aesthetics, but also their work practices. It was, however, the Belgian, Marcel Broodthaers who saw the future. Duchamp’s aversion to manual labour was the precedent, but Broodthaers understood the shift from blue to white-collar culture.

In 1968 Broodthaers created his Museum of Modern Art, Department of Eagles, a conceptual museum. Antagonists to painting, such as Benjamin Buchloh have cited this work as the moment when the contemporary artist’s role shifted from artisanal to managerial, the self-expressive to the conceptual. It is no coincidence that this moment mirrors the shift in the western economy from manufacturing to knowledge industries in the late twentieth century.

The managerial is now seen to be a progressive mode of artistic production. Underlying this is the belief that that all advanced art is conceptual. In Joseph Kosuth’s words, a work of art is a kind of proposition presented within the context of art as a comment on art. Painting now exists alongside installation, performance, film and interactive media.

The works in Old Europe evolved in full awareness of this proposition of the broader context in which painting finds itself. In different ways, the works are provocations about their context, much as Kosuth might articulate it. But rather than assuming that the language of painting is redundant, Persson enjoys a freedom to choose from its rich heritage.

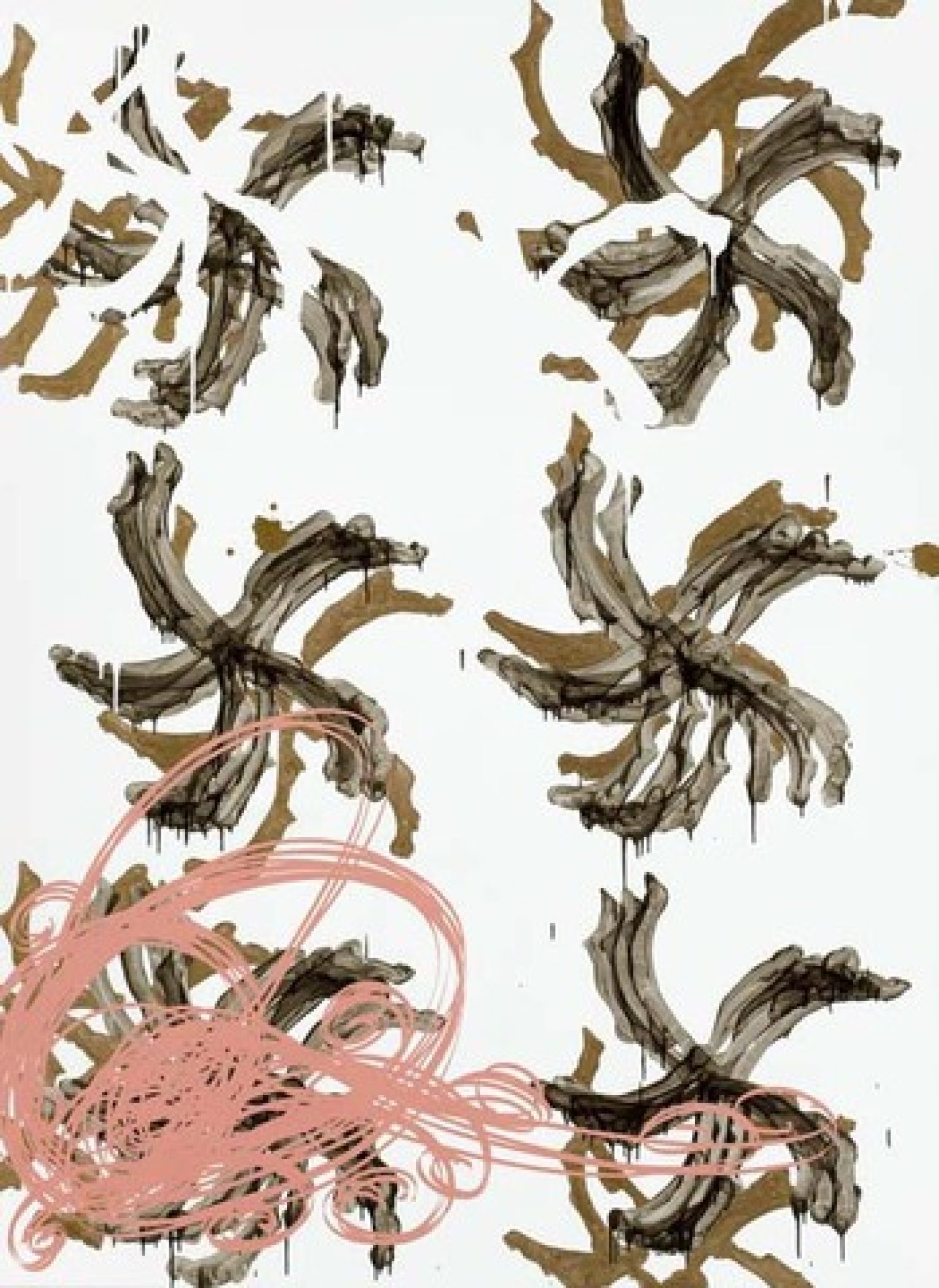

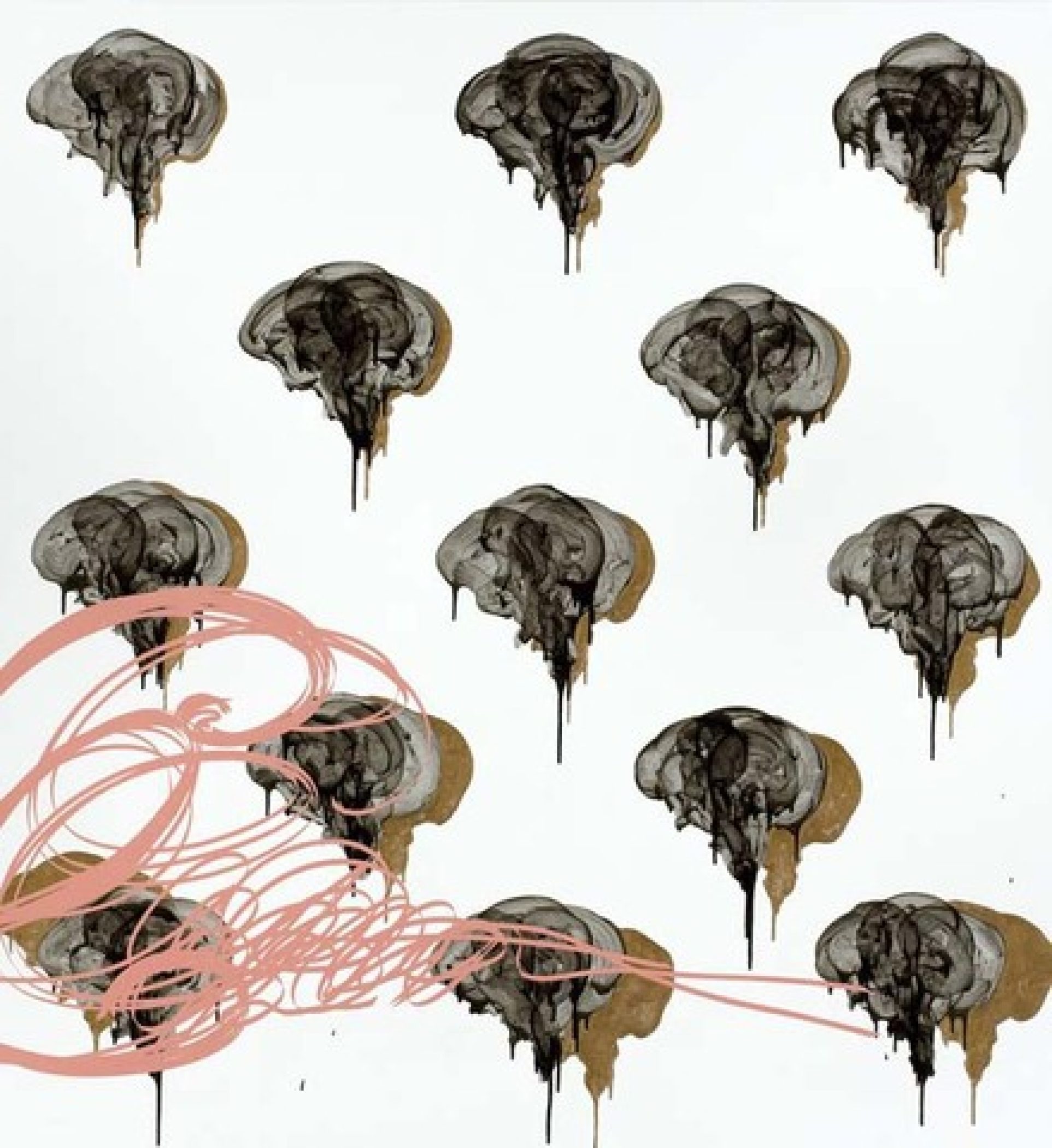

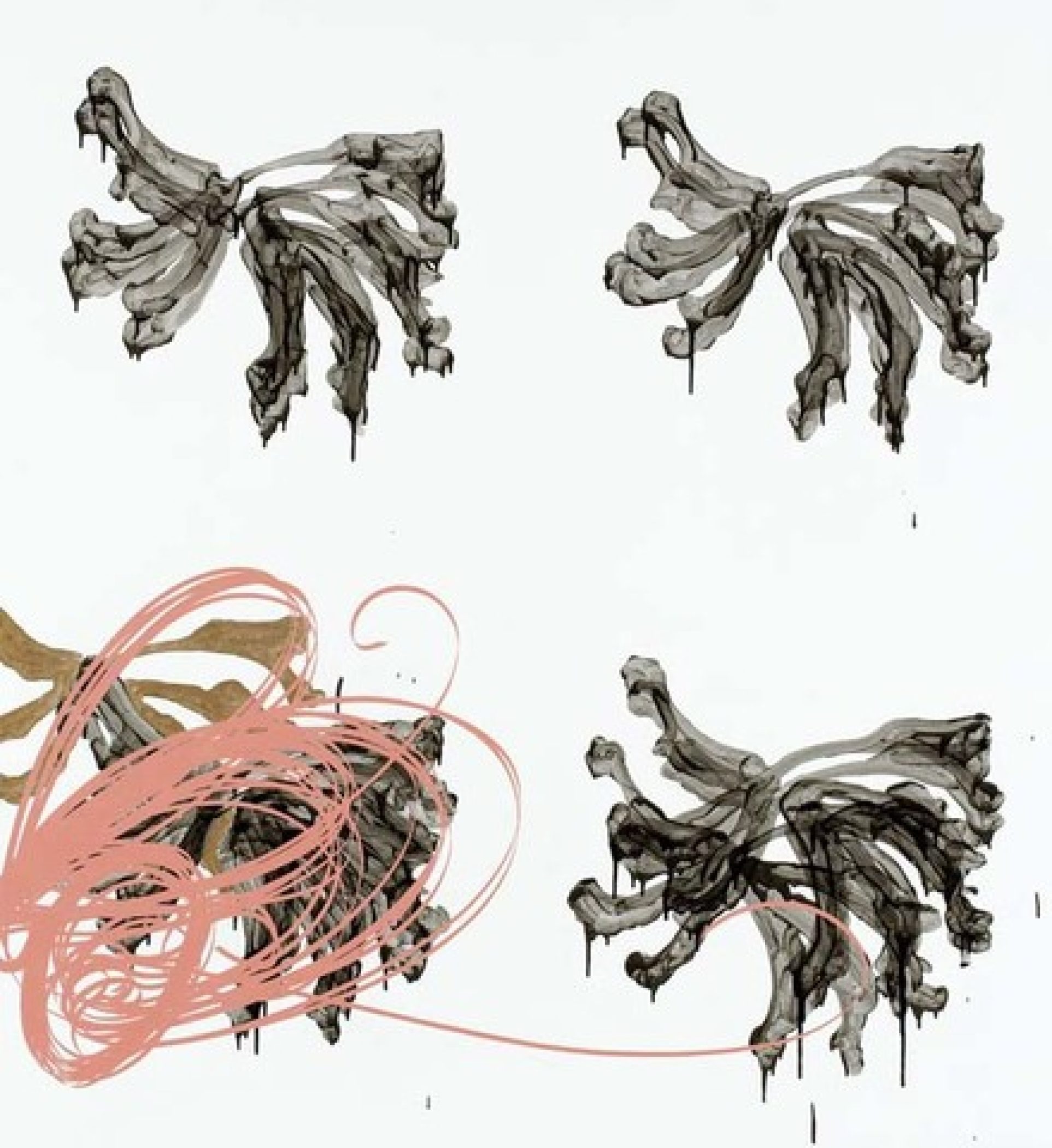

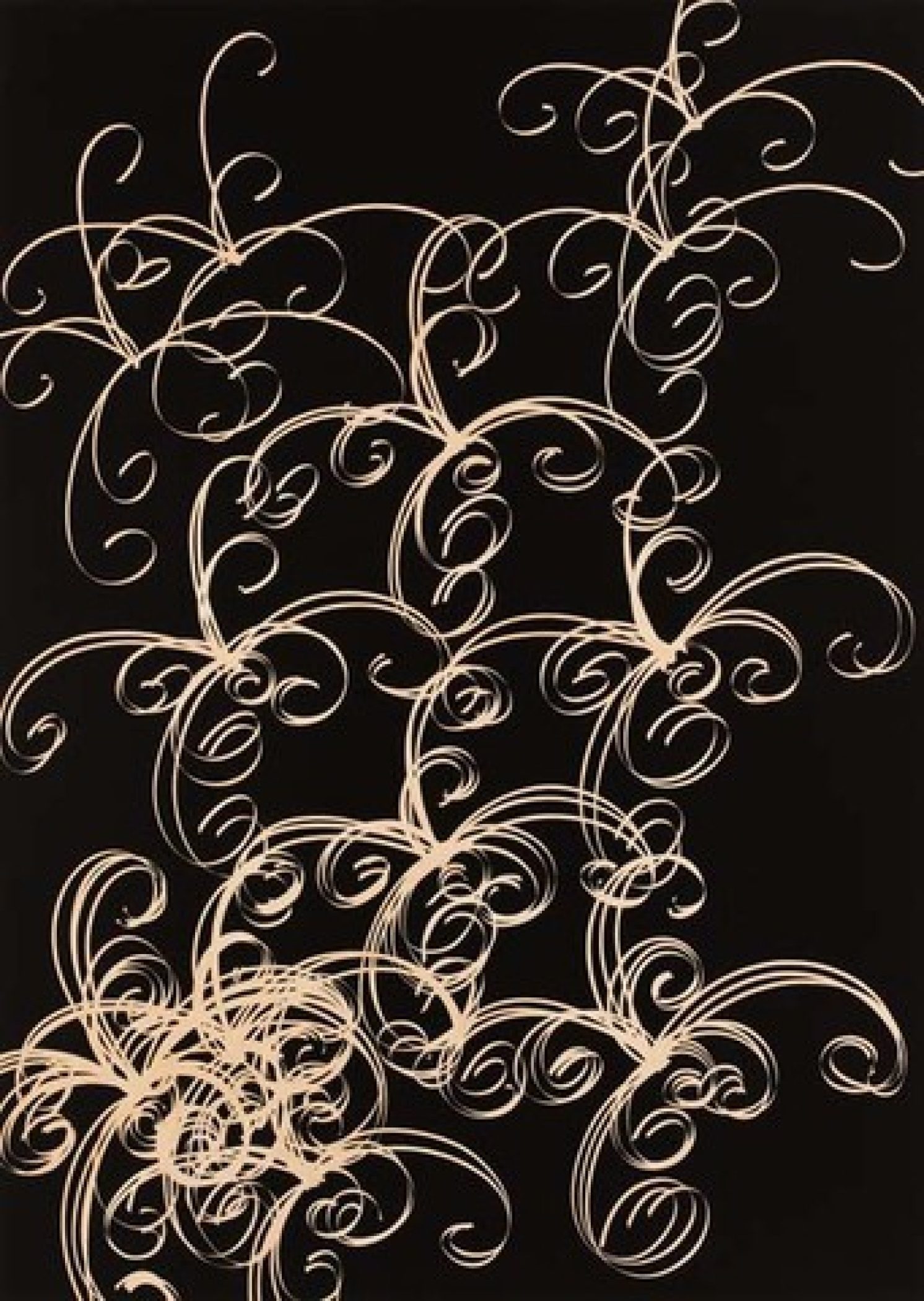

Flat expanses of hard-edged colour collide with soft translucent forms. Organic forms are subject to simple compositions, formal and heraldic. They are repeated, but never precisely. Some shapes have shadows but they are made with light reflective metallic paint. The gestures drip freely only to be entombed by the painted ground. Decorative scrolls, pink and blue, black and white, brand the paintings, perhaps forming letters or even words, perhaps not. Always there is a dance between the materiality of the work and the wit of its elusive subject matter, hinted at in the titles, but inevitably returning the viewer to the complexity of the physical painting itself.

The project bypasses the exhausted debates about painting’s relevance. It restates the possibilities that painting continues to offer and is a dedicated exploration of its history, the hidden foundation of all contemporary art, its European origins, its European DNA.

Images

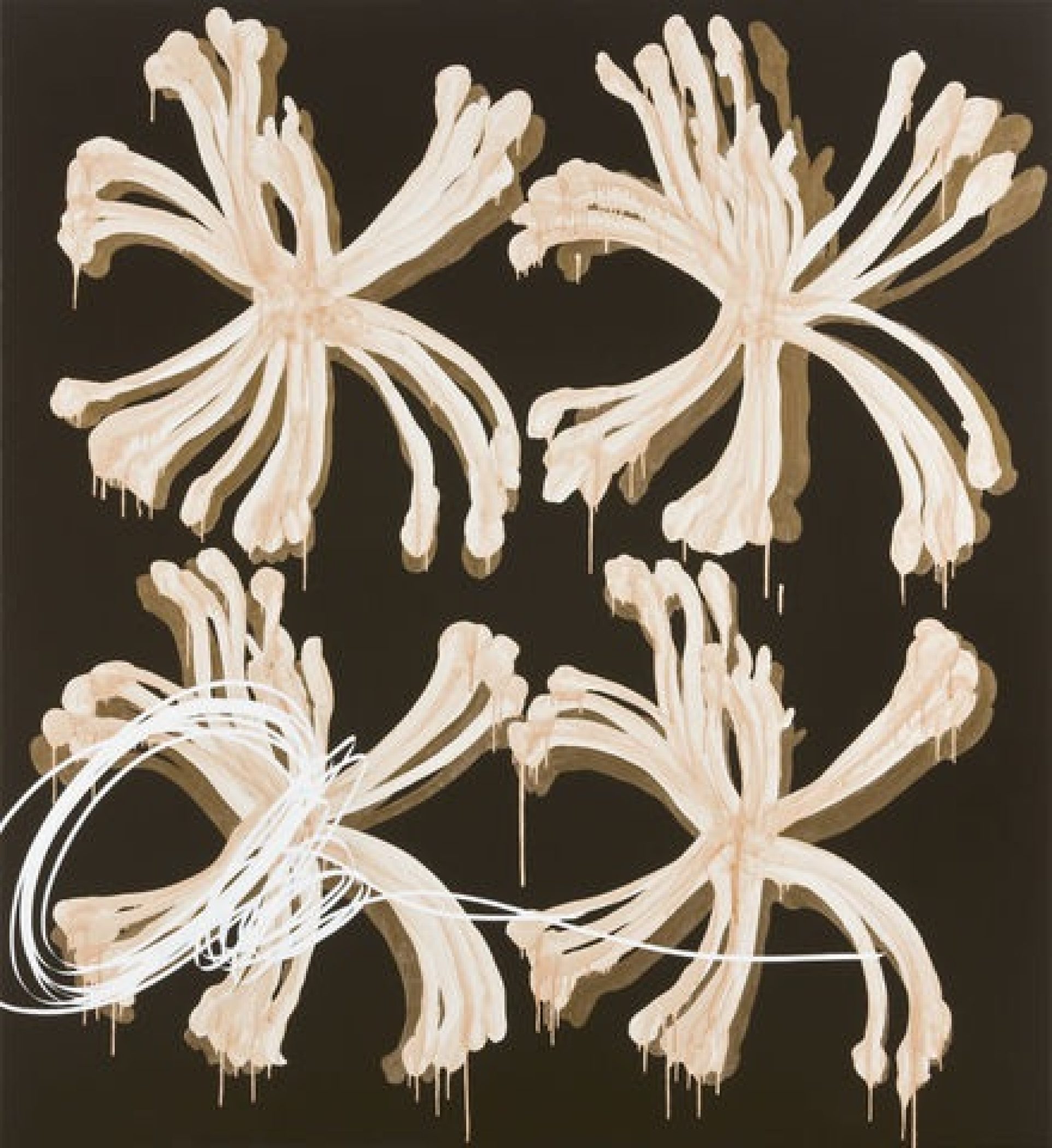

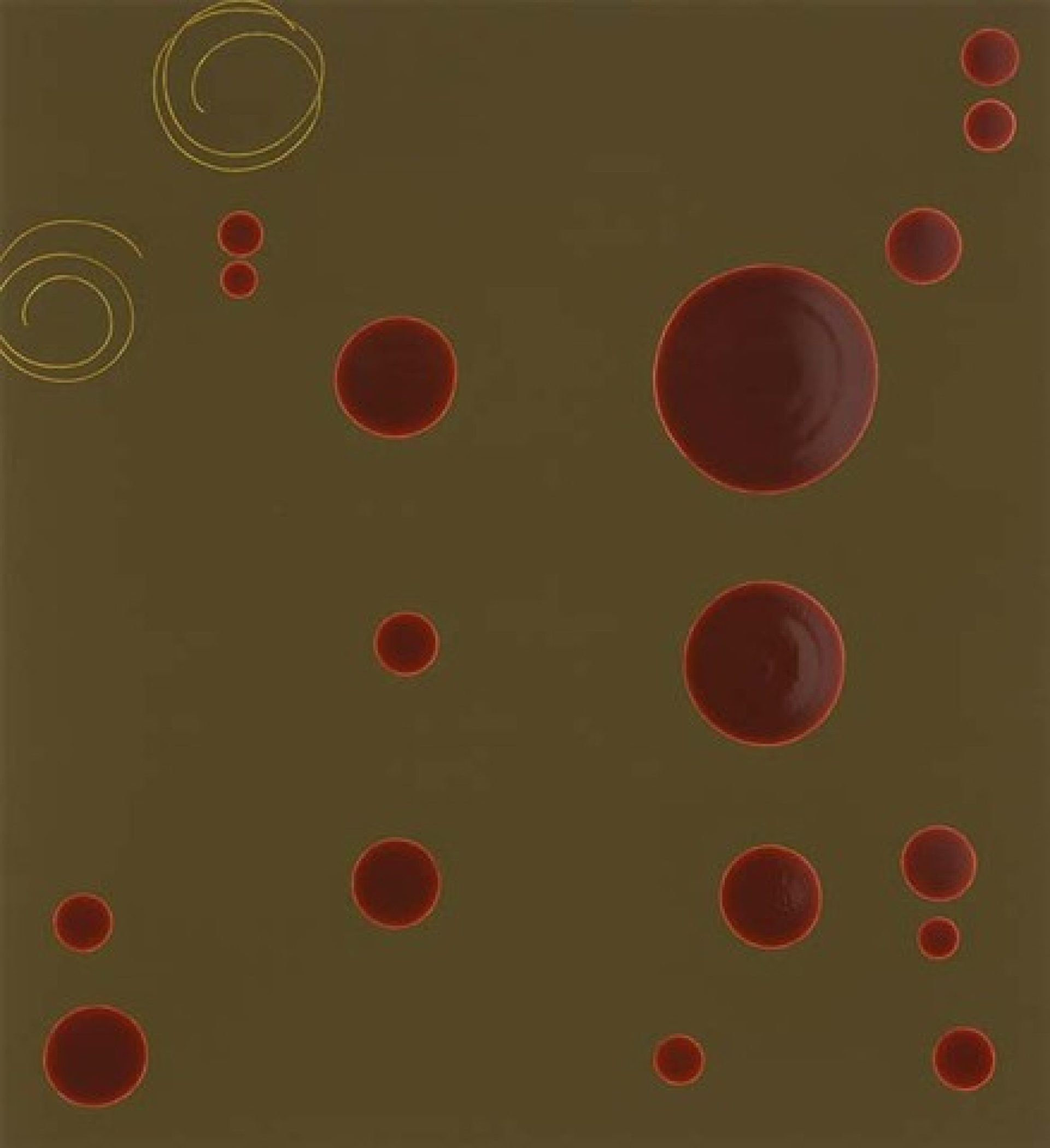

Stieg Persson

Old Europe, 2008

Installation view, Anna Schwartz Gallery, Carriageworks

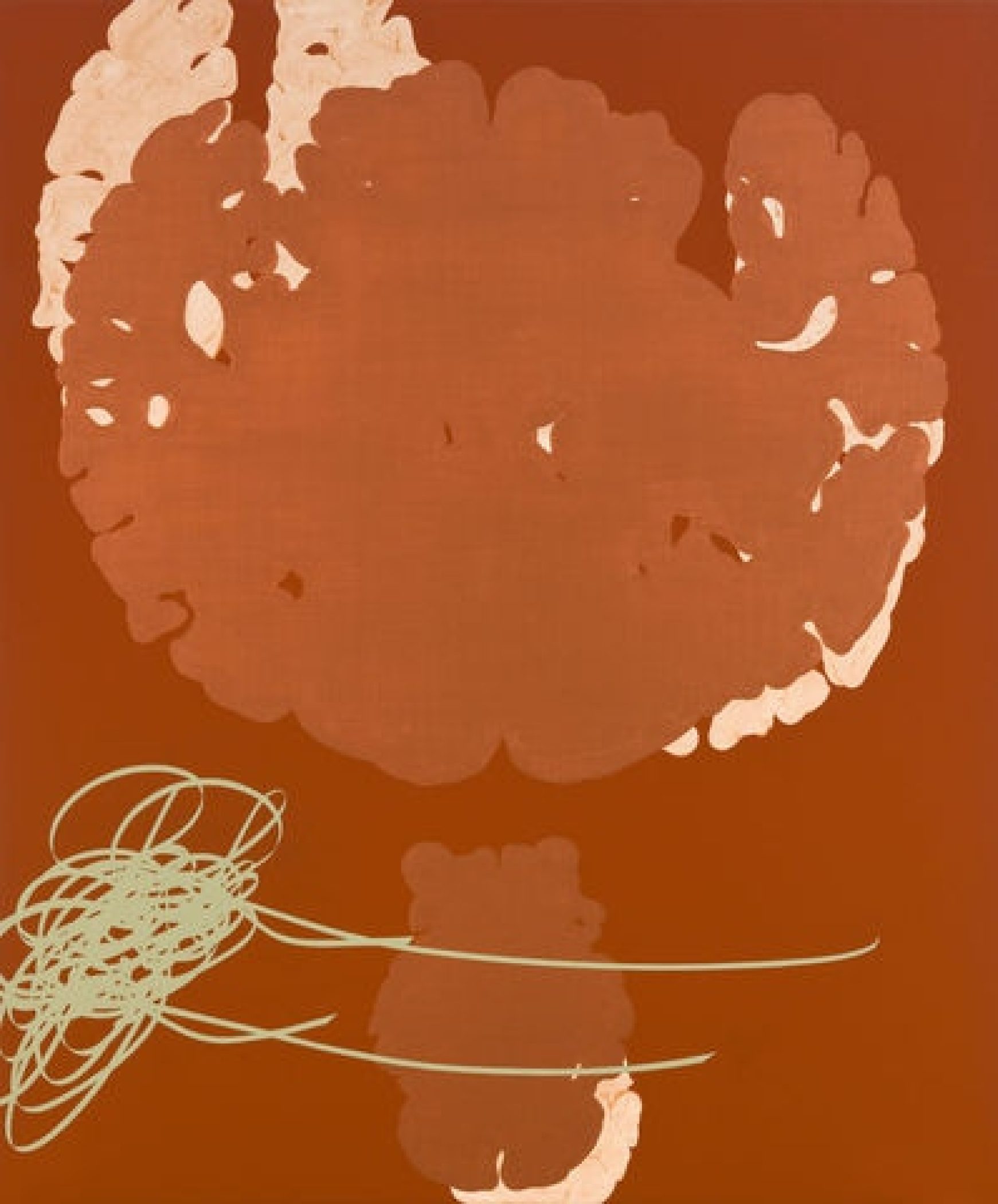

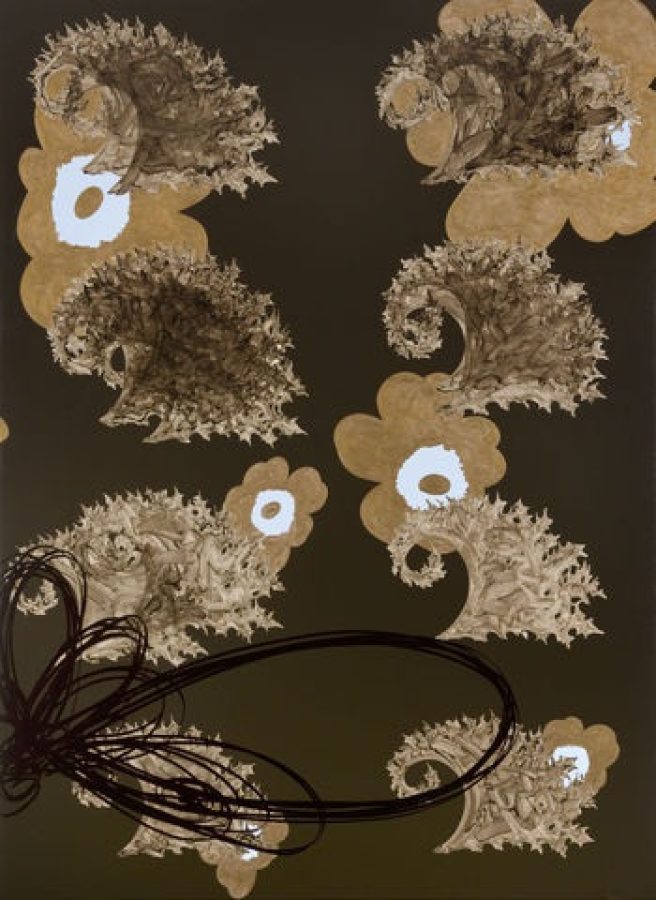

Stieg Persson

Old Europe, 2008

Installation view, Anna Schwartz Gallery, Carriageworks

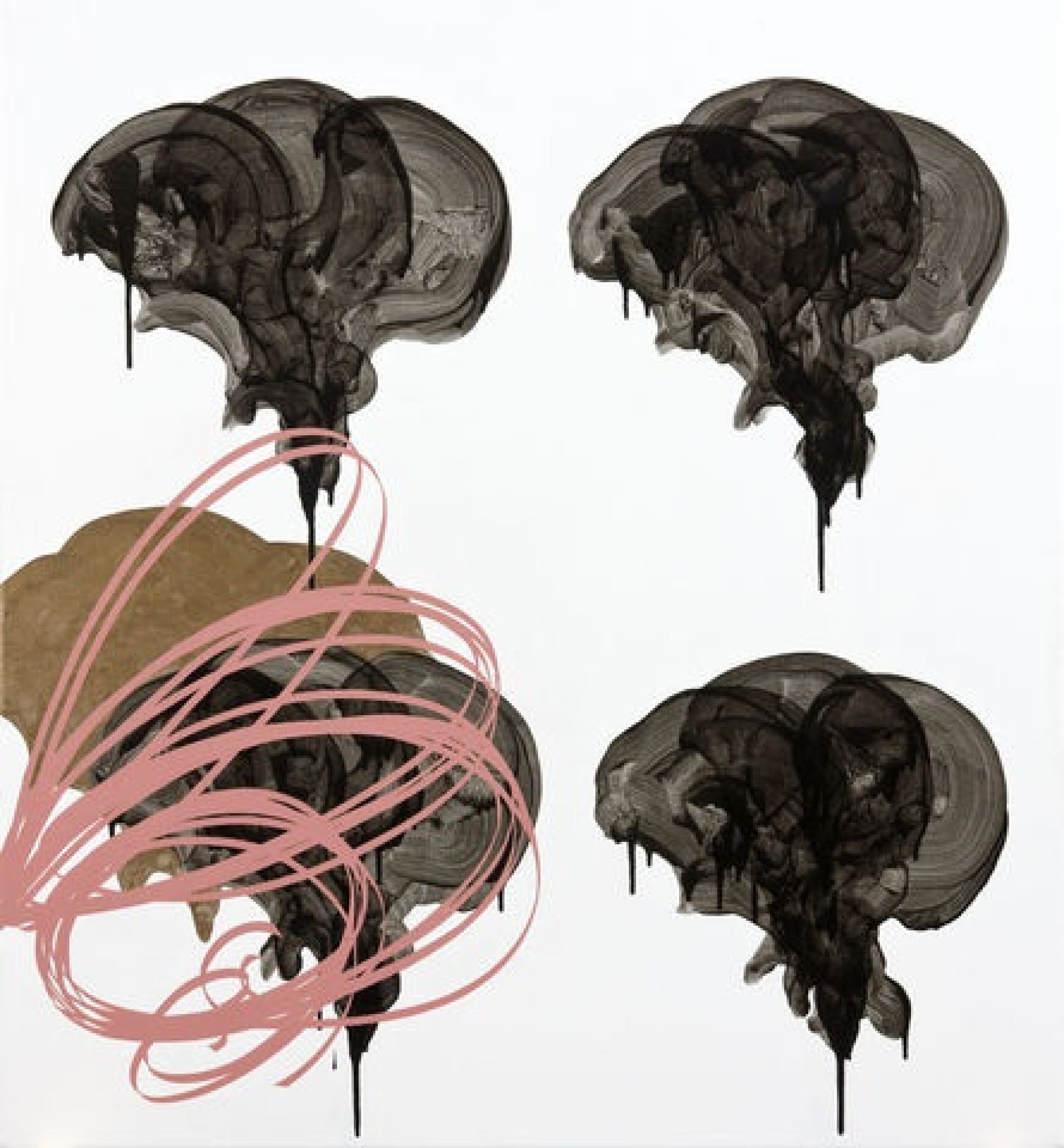

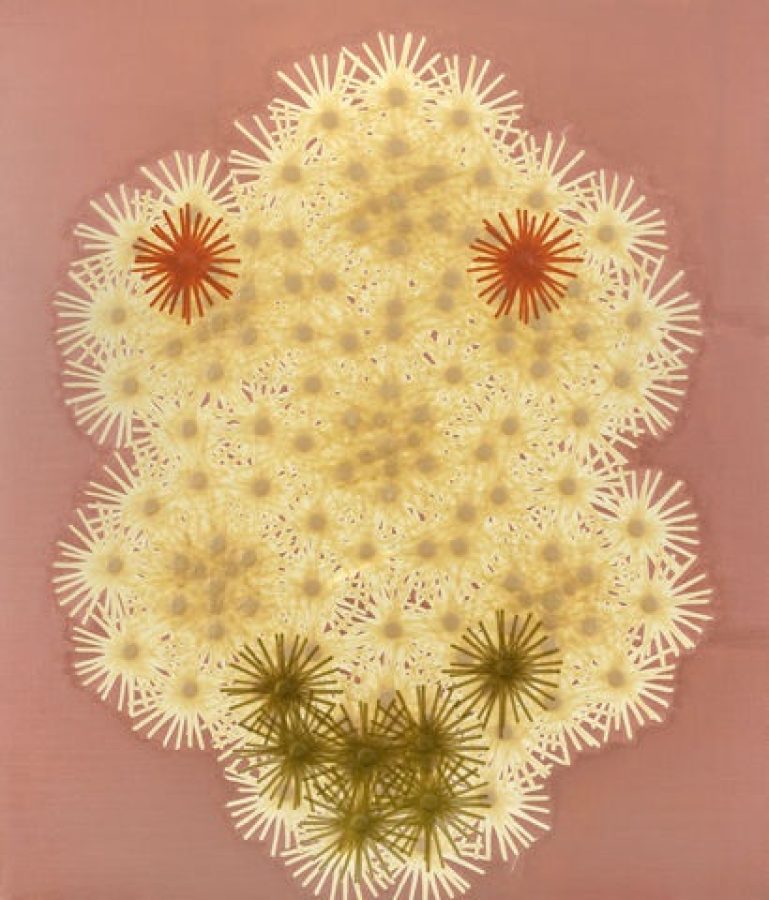

Stieg Persson

Old Europe, 2008

Installation view, Anna Schwartz Gallery, Carriageworks

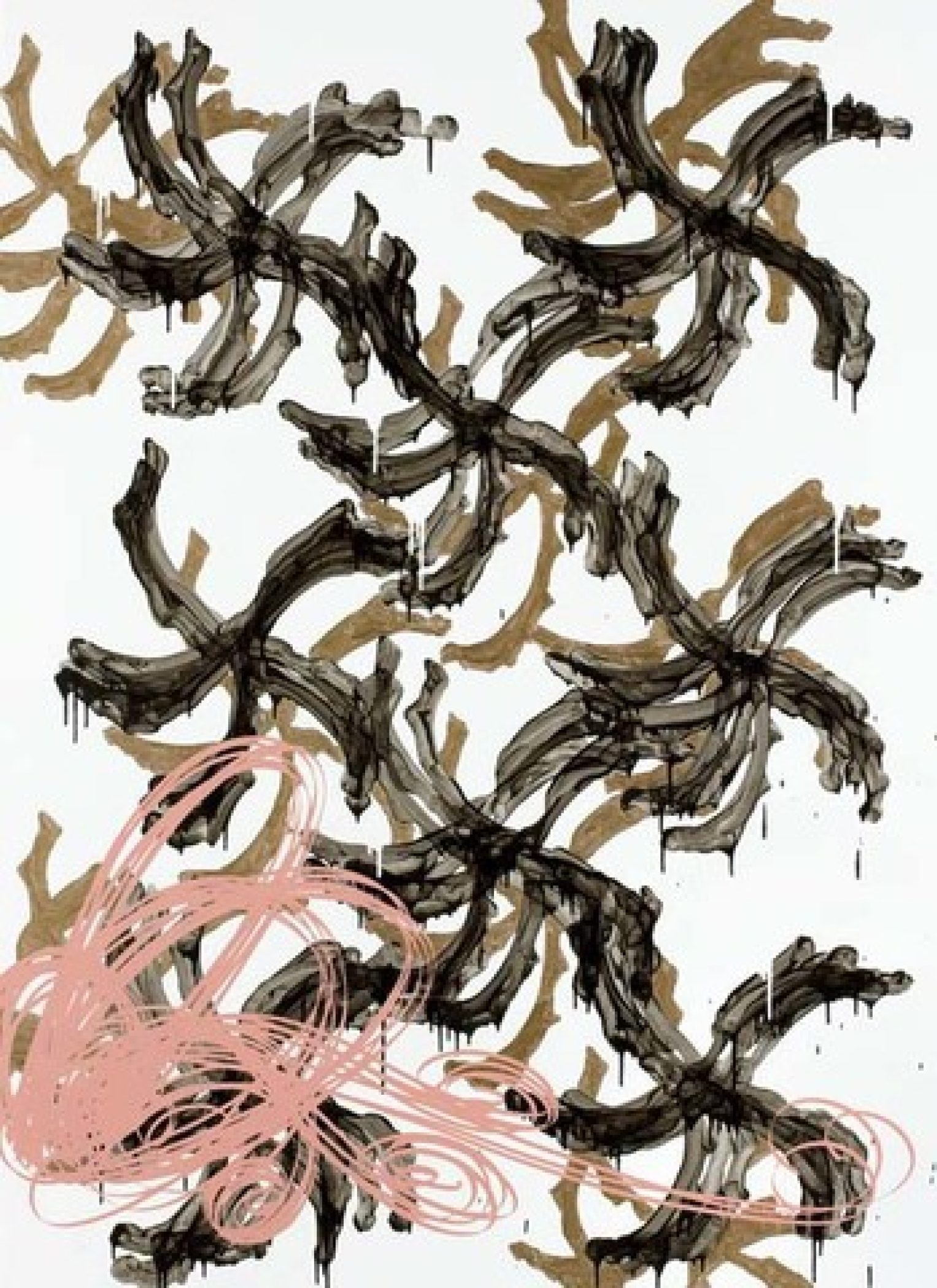

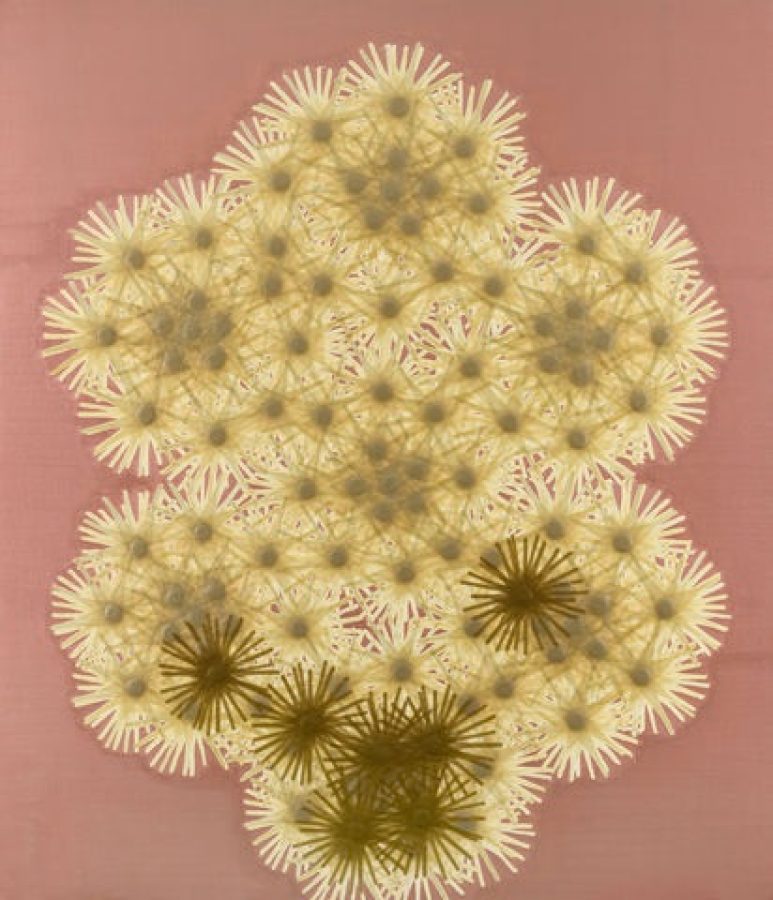

Stieg Persson

Old Europe, 2008

Installation view, Anna Schwartz Gallery, Carriageworks

Stieg Persson

Old Europe, 2008

Installation view, Anna Schwartz Gallery, Carriageworks

Old Europe, 2008

Installation view, Anna Schwartz Gallery, Carriageworks

Stieg Persson

Old Europe, 2008

Installation view, Anna Schwartz Gallery, Carriageworks

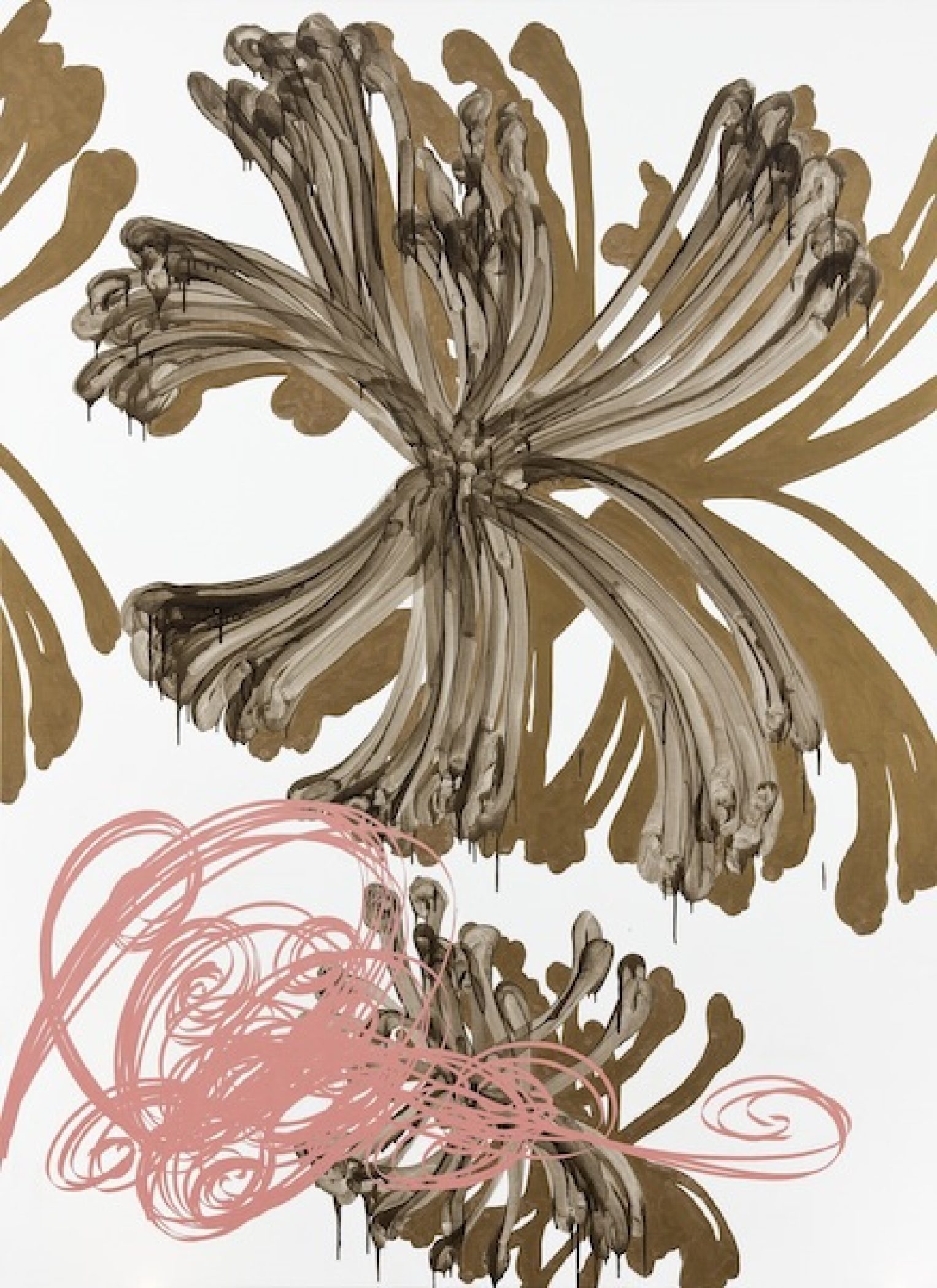

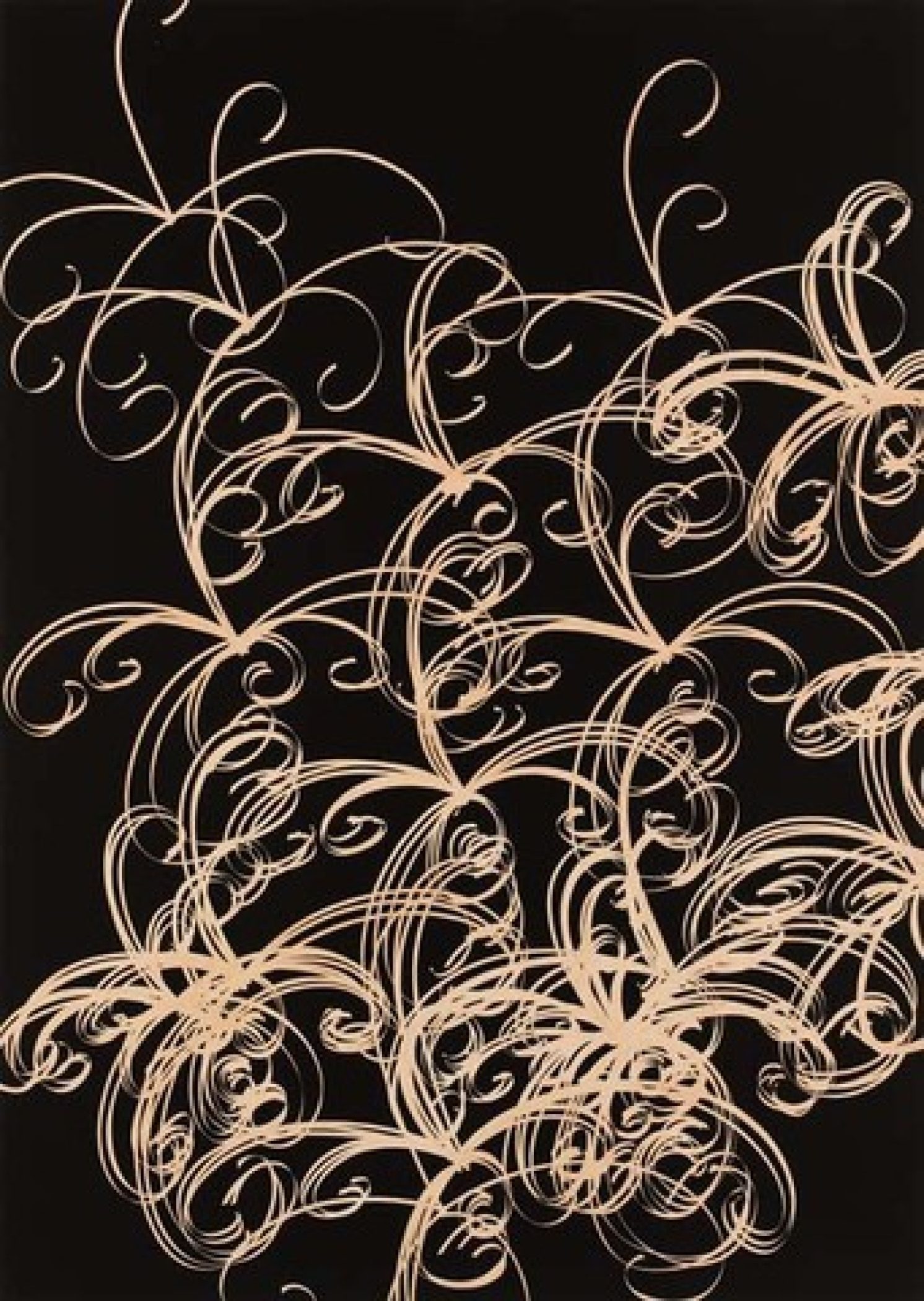

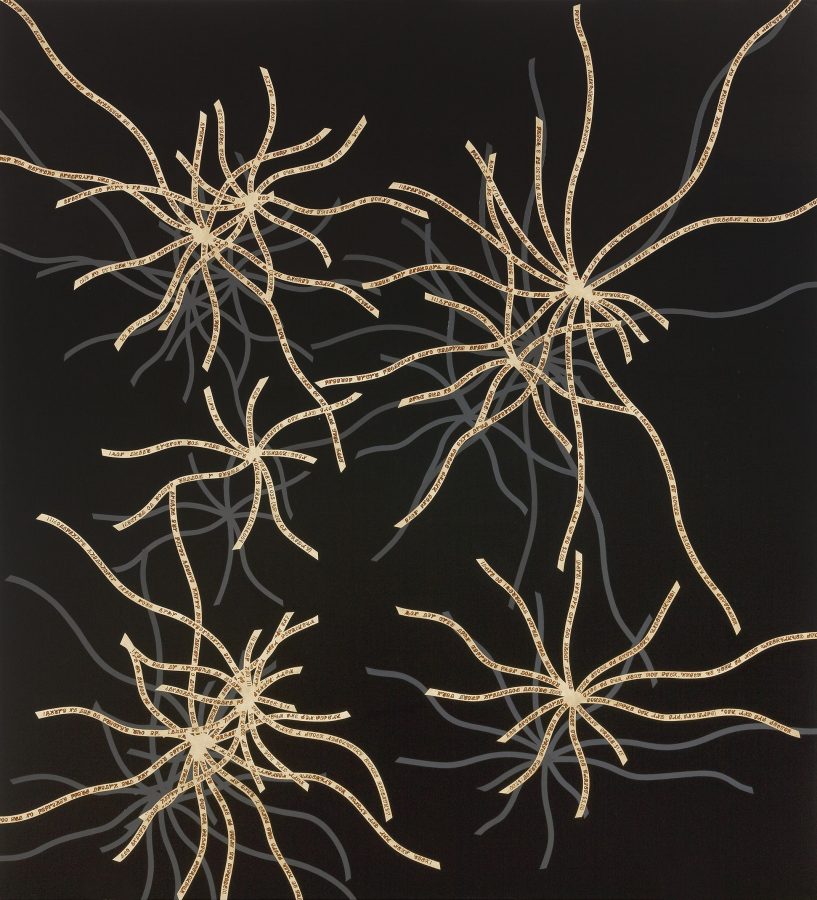

Stieg Persson

Second Empire, 2008

Oil and metallic paint on linen

229 x 167 cm

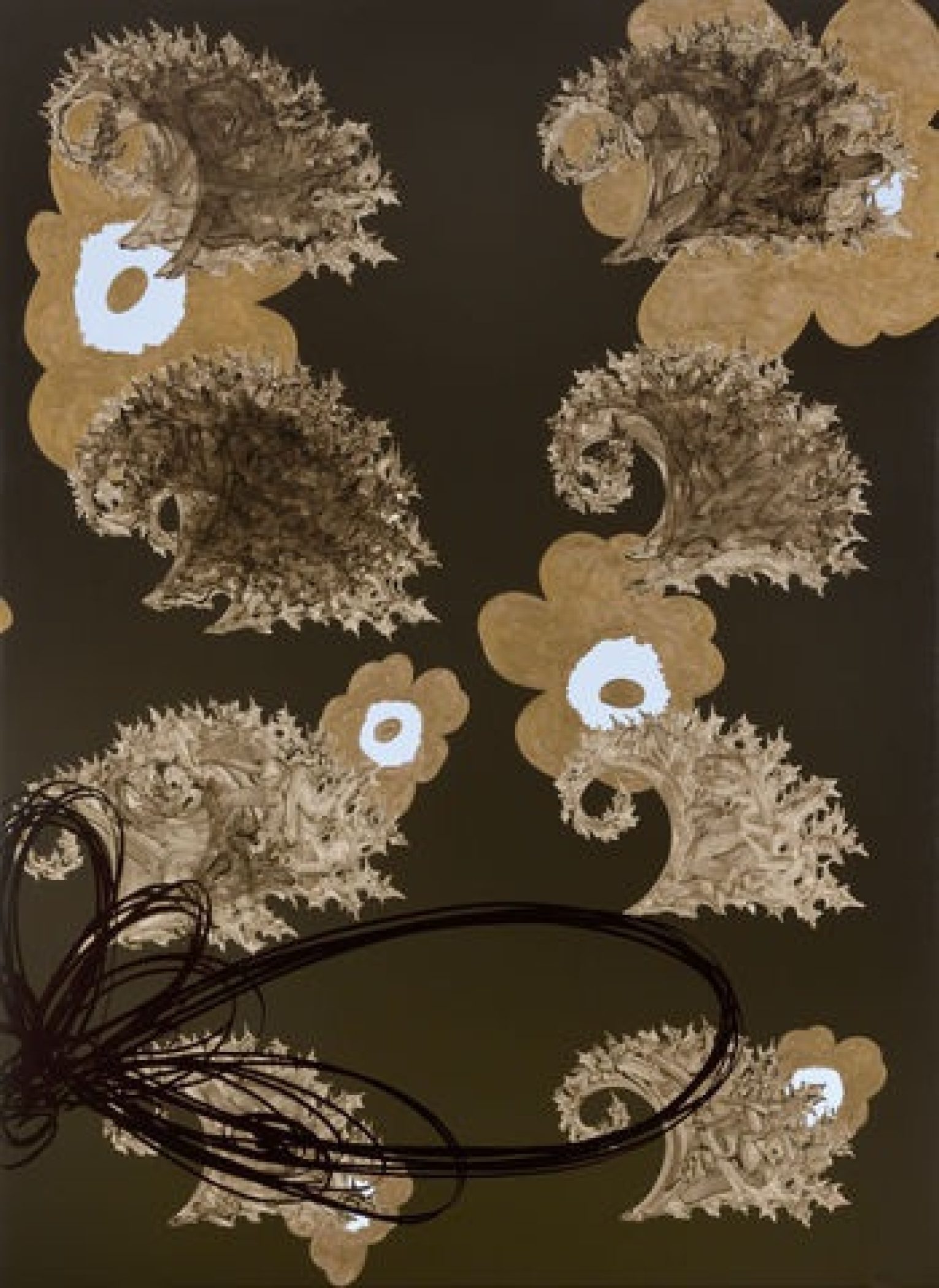

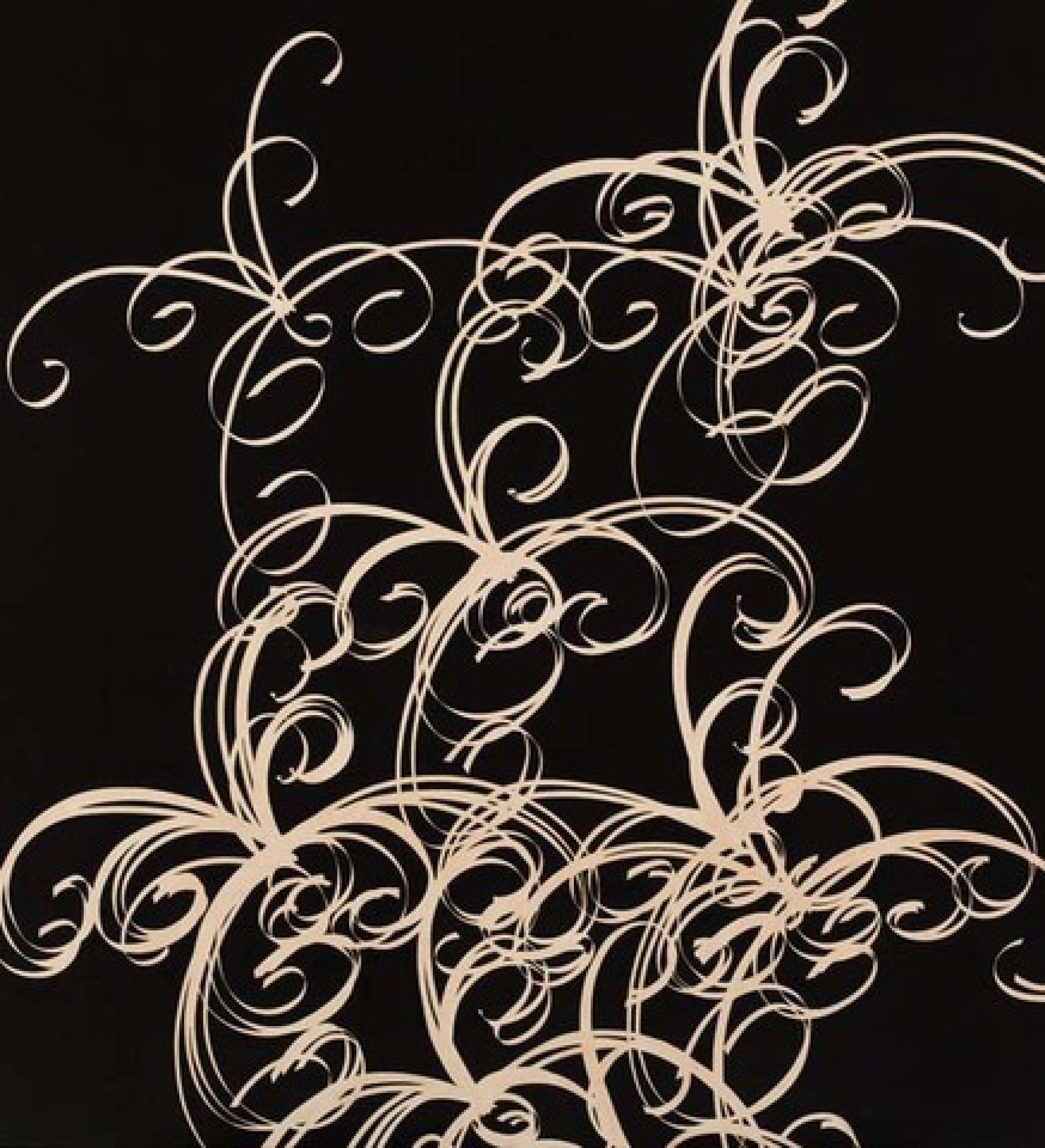

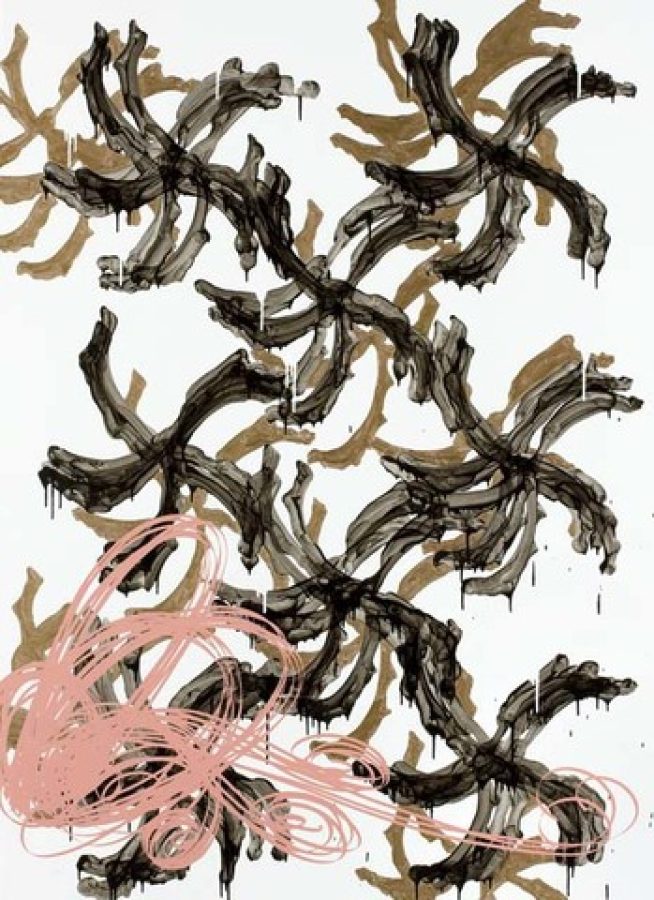

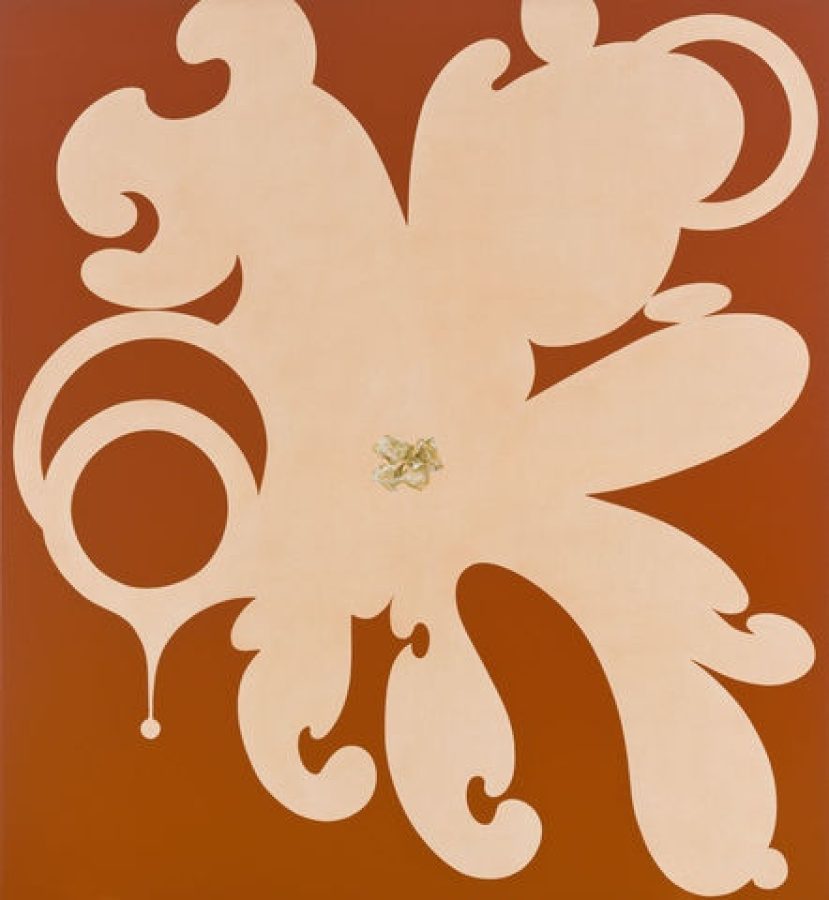

Stieg Persson

Third Republic III, 2008

Oil and metallic paint on linen

229 x 167 cm

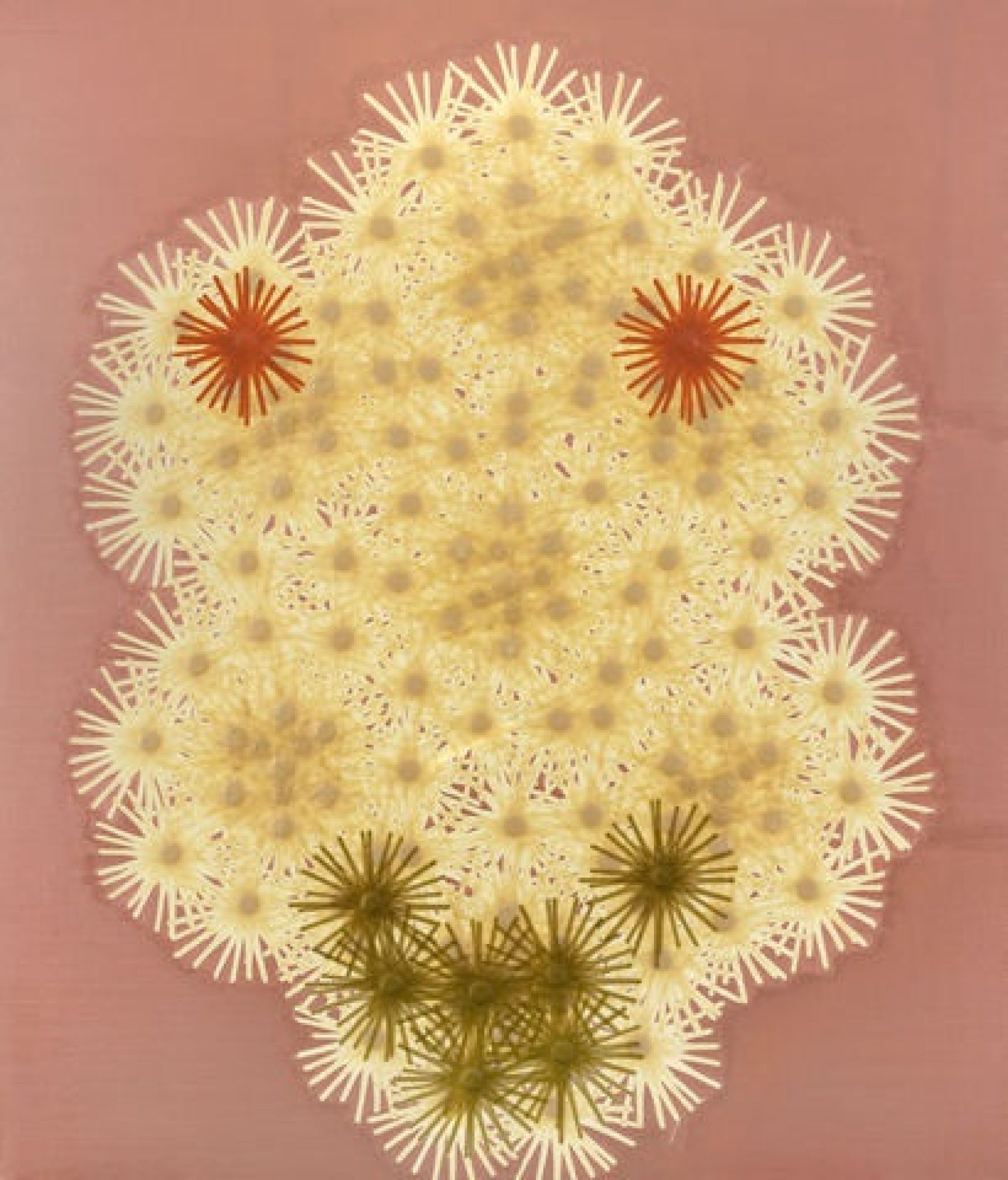

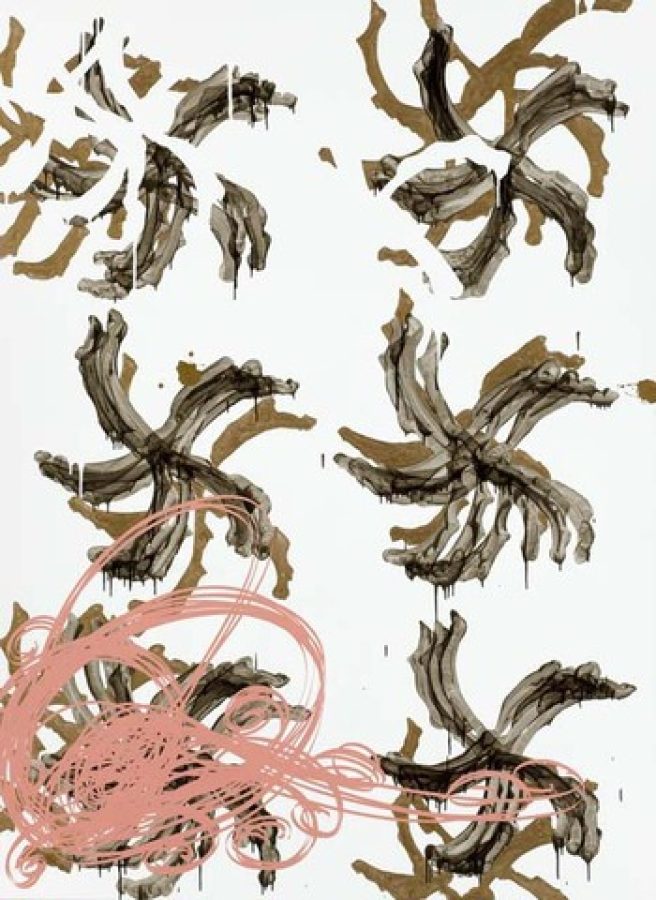

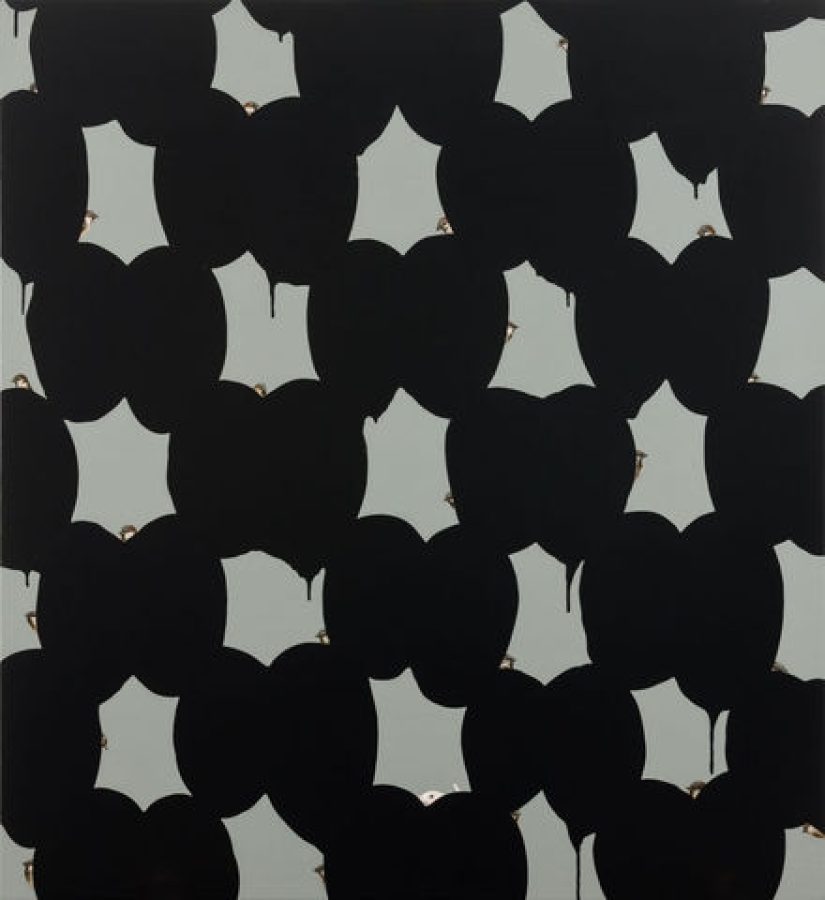

Stieg Persson

Ruskin, 2008

Oil and metallic paint on linen

229 x 167 cm

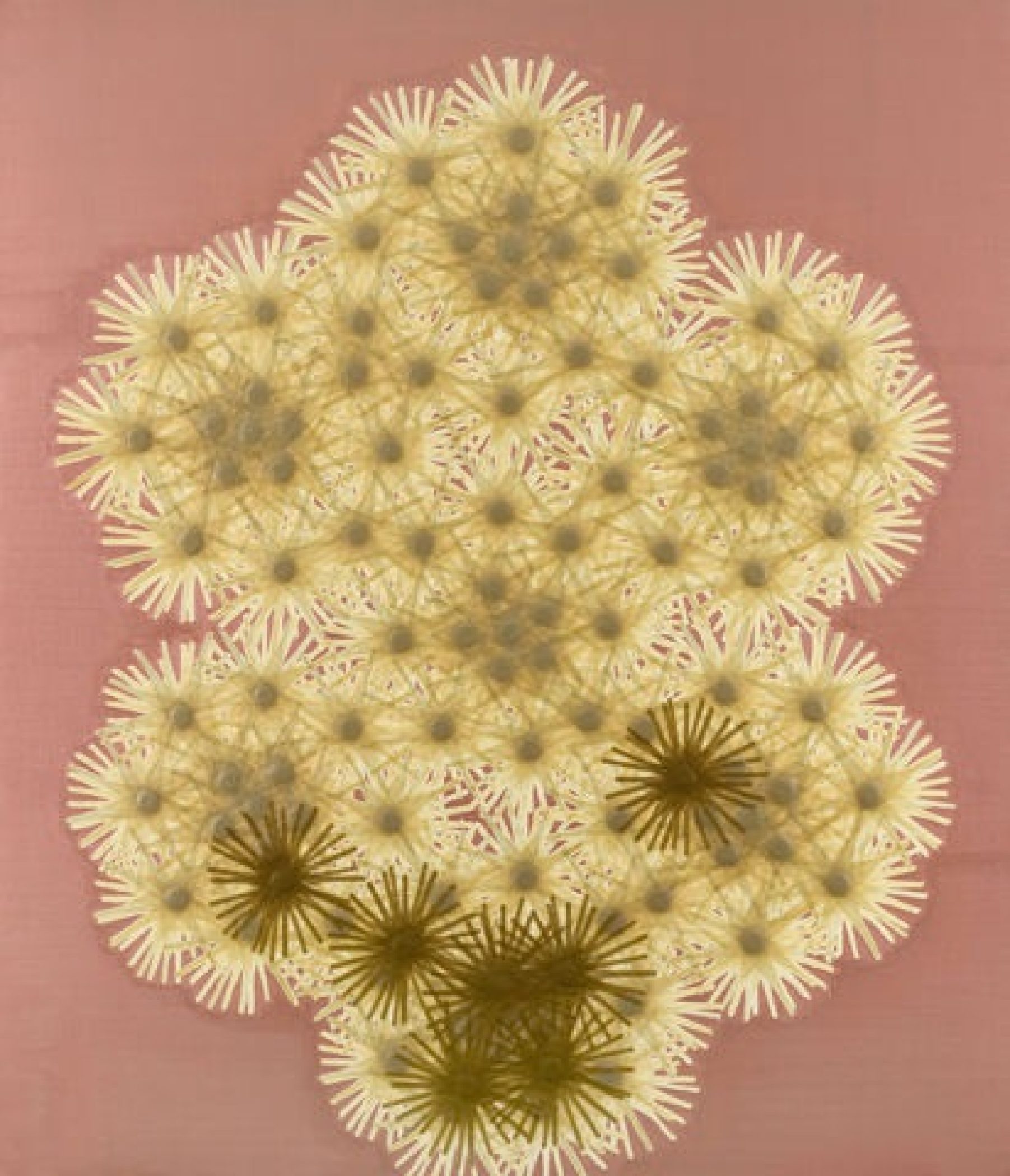

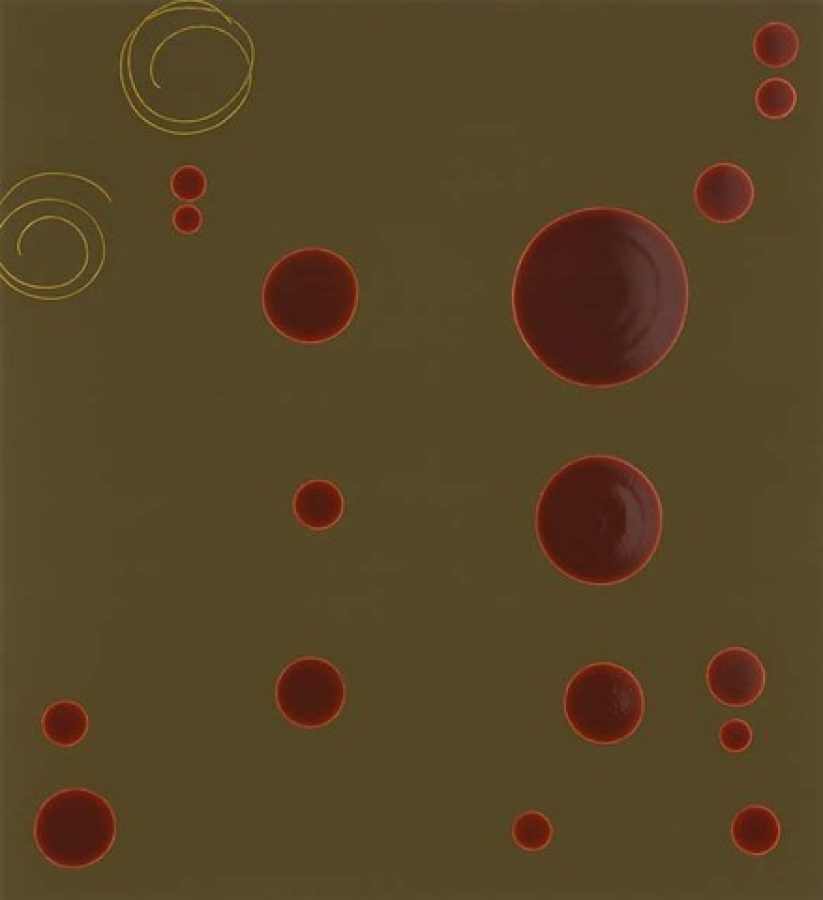

Stieg Persson

Das Alte Europa, 2008

Oil and metallic paint on linen

229 x 167 cm

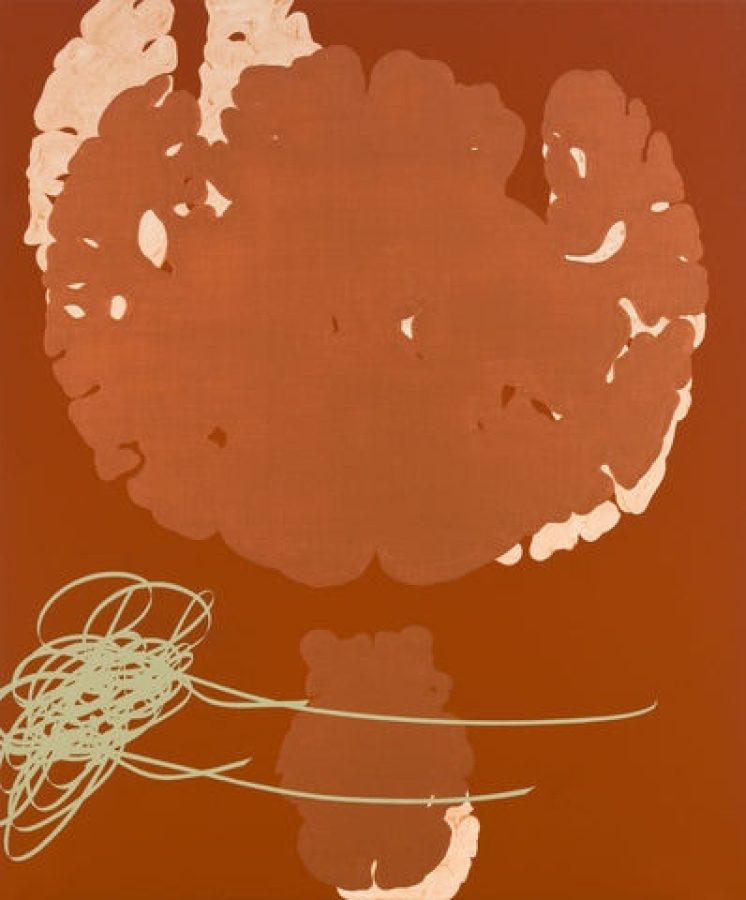

Stieg Persson

Ségolène Royal, 2008

Oil and alkyd resin on linen

213 x 183 cm

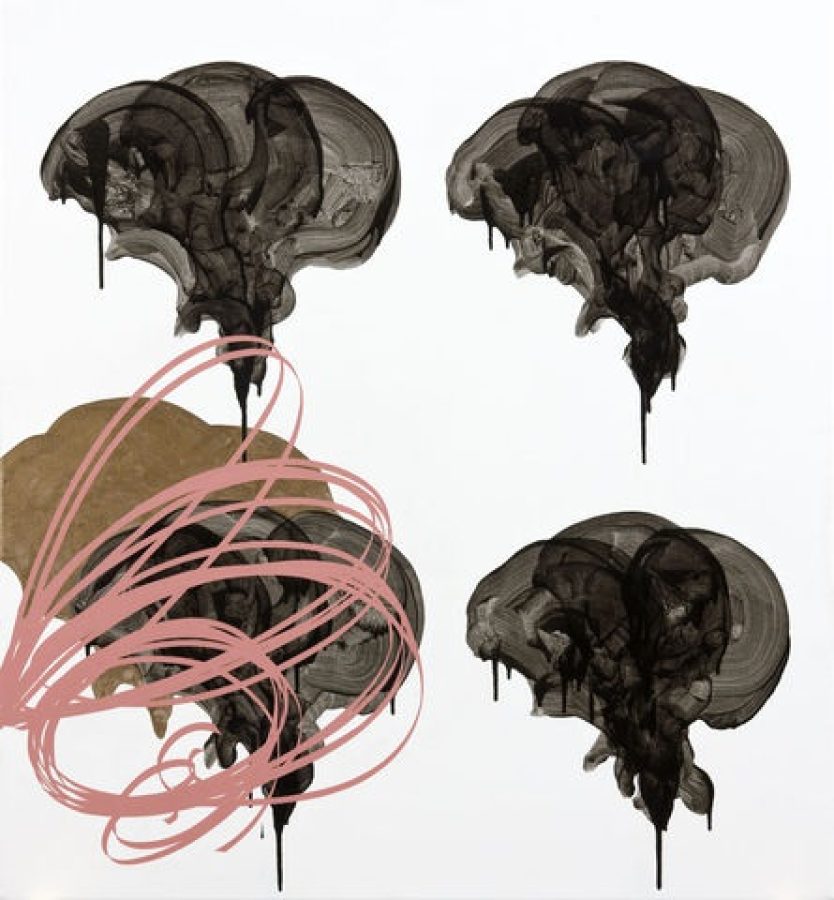

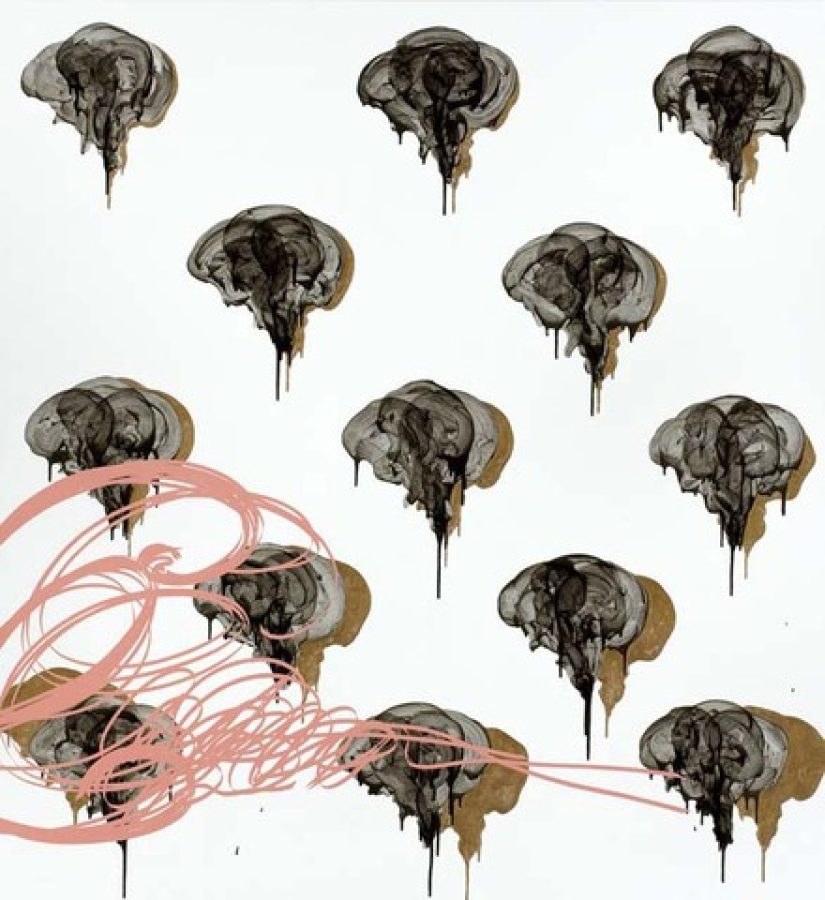

Stieg Persson

Gerhard Schröder, 2008

oil and alkyd resin on linen

213 x 183 cm

Stieg Persson

Herculex®, 2008

Oil and alkyd resin on linen

219 x 183 cm

Stieg Persson

Martyrdom, 2008

Oil and metallic paint on linen

183 x 168 cm

Stieg Persson

Ga ga, 2008

Oil and metallic paint on linen

153 x 128 cm

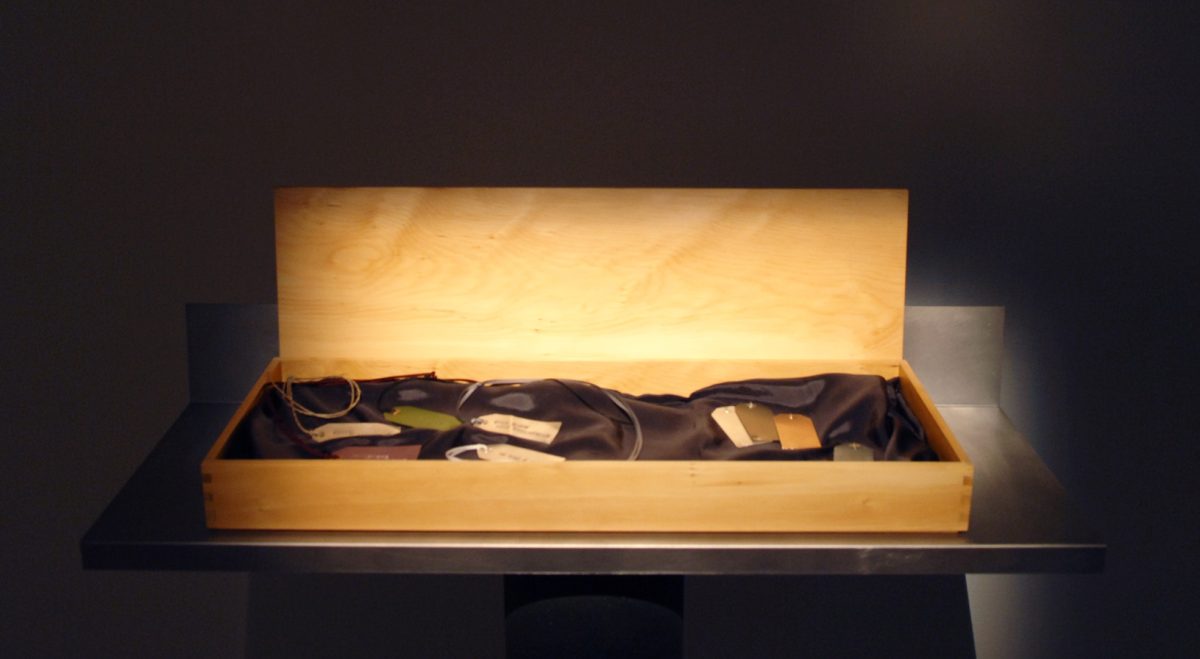

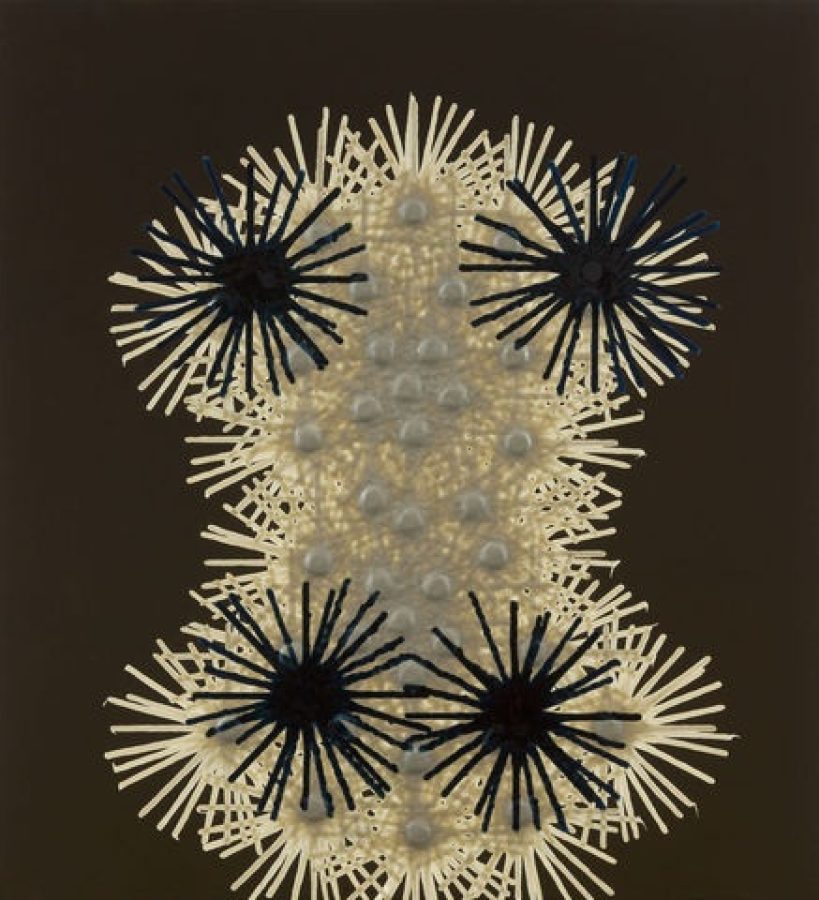

Su san Cohn

Goodbye, 2015

60 x 22 x 7 cm; digital video: 1 minute

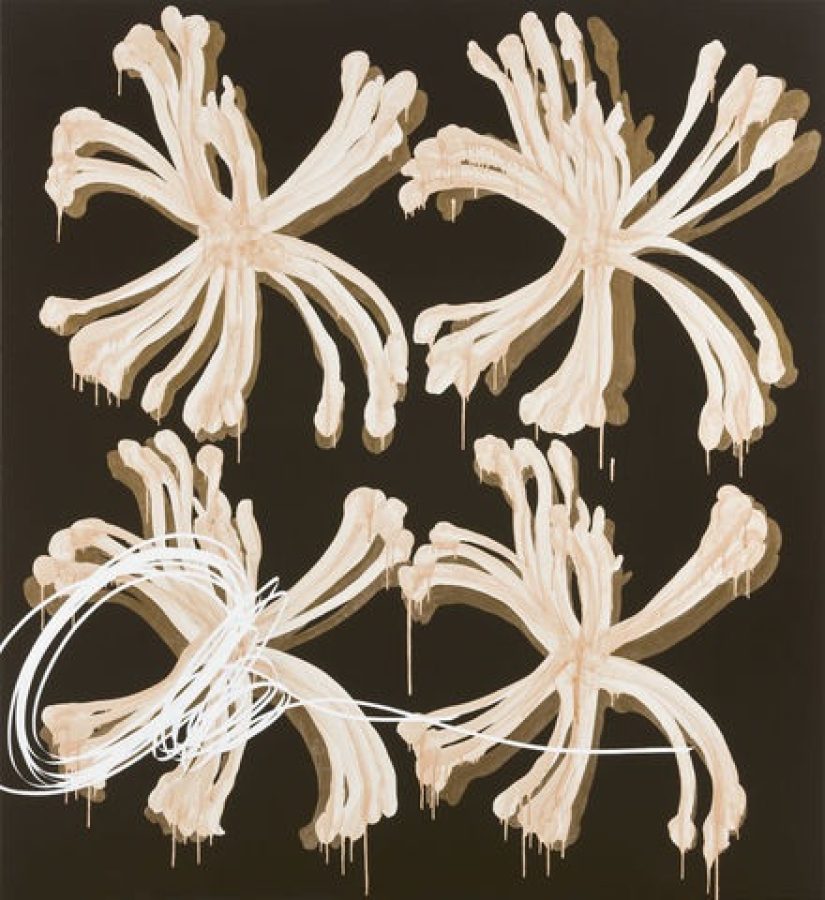

Say Goodbye to Agapanthus, 2008

Oil and metallic paint on linen

154 x 128 cm

Stieg Persson

Little Gerhard, 2008

oil and alkyd resin on linen

122 x 112 cm

Stieg Persson

Little Northern Blight, 2008

Oil and alkyd resin on linen

122 x 112 cm

Stieg Persson

Albertine, 2008

Oil and metallic paint on linen

122 x 112 cm

Stieg Persson

Common Smut, 2008

Oil and alkyd resin on linen

122 x 112 cm

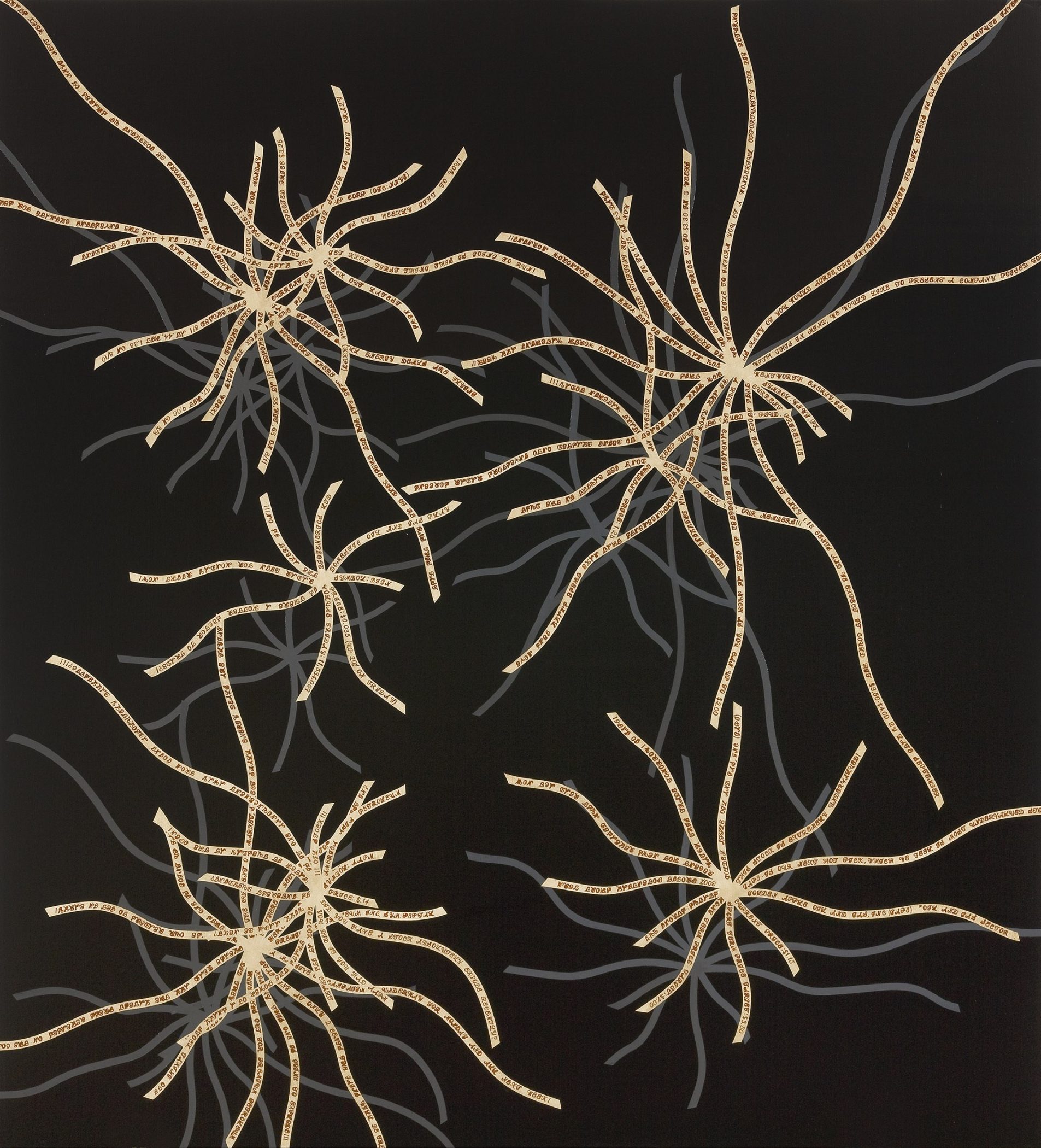

Stieg Persson

Winckelmann in Trieste, 2008

Oil and metallic paint on linen

229 x 167 cm

Stieg Persson

Signor Giovanni, 2008

Oil and metallic paint on linen

229 x 167 cm

Stieg Persson

Ermine, 2008

Oil and metallic paint on linen

183 x 168 cm

Stieg Persson

Monsieur de Charlus, 2008

Oil and metallic paint on linen

183 x 168 cm

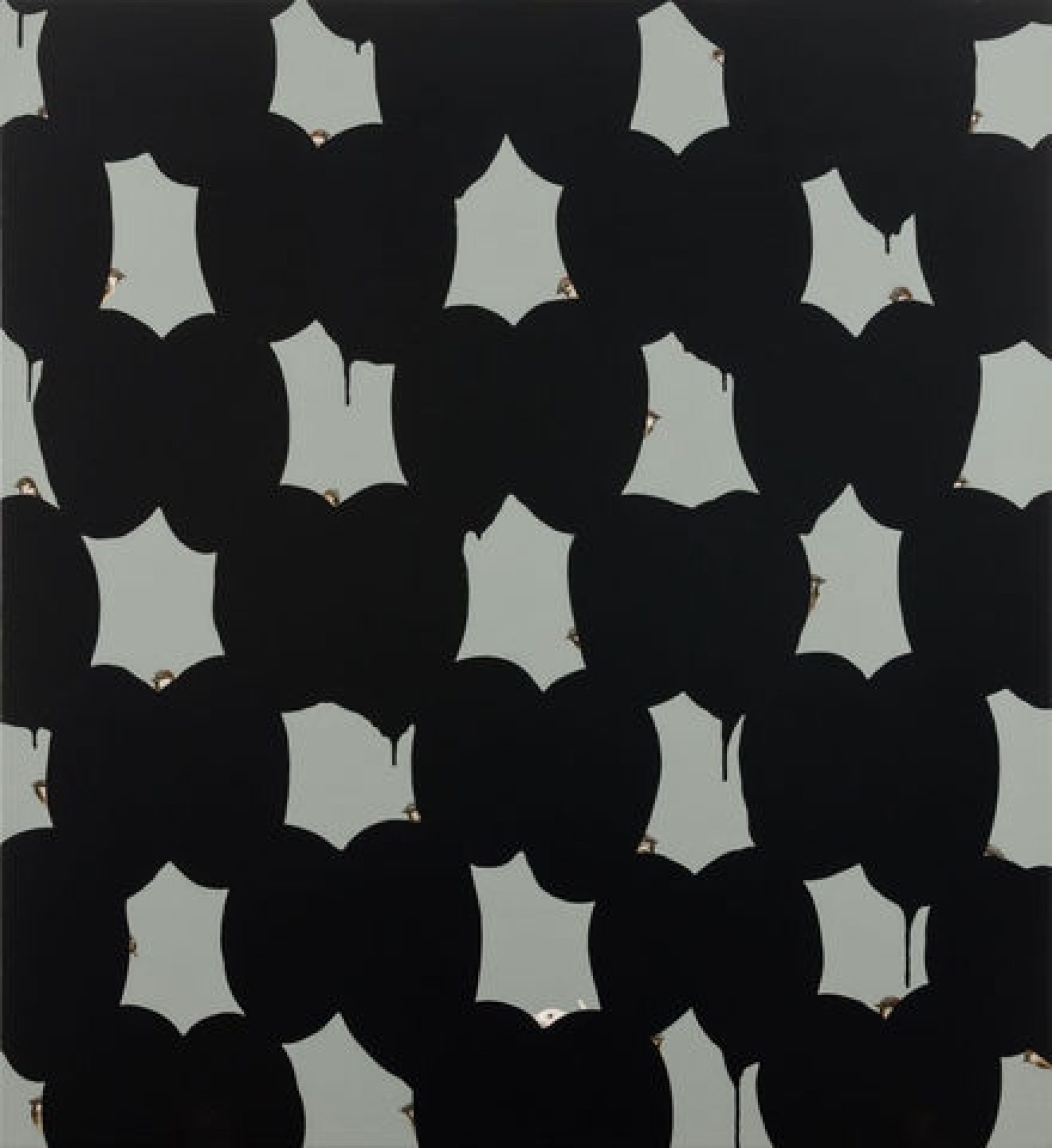

Stieg Persson

Race to the Bottom, 2008

Oil on linen

213 x 152 cm

Stieg Persson

Downward Harmonisation, 2008

Oil on linen

213 x 152 cm

Stieg Persson

Sarbanes-Oxley, 2008

Oil on linen

122 x 112 cm

Stieg Persson

Frenched, 2007

Oil and metallic paint on linen

213 x 152 cm

Stieg Persson

Judgement of Paris, 2007

oil on linen

183 x 168 cm

Stieg Persson

Present, 2007

Oil and metallic paint on linen

183 x 168 cm

Stieg Persson

Vair, 2007

Oil on linen

183 x 168 cm

Stieg Persson

Clash Theory, 2006

Oil & alkyd resin on linen

183 x 168 cm