Marco Fusinato

Noise & Capitalism

2nd September – 2nd October 2010

Anna Schwartz Gallery

Since Gutenberg, every major political upheaval has been at least partially provoked and promulgated by a tidal-wave of hard-hitting pamphleteering. As the French situationist Guy Debord put it, not books but pamphlets change the world. Modern politics is unthinkable without innumerable ideologists committed to promoting their message as effectively as they can. Short, sharp, insurrectionary, the form of the pamphlet is itself the basis for the genre of the manifesto, in which conspiracies are allegedly exposed, principles of revolt declared, justice affirmed, and organizations consolidated. The pamphlet is the preferred tool of those desiring to be what the Bulgarian writer Elias Canetti once referred to in Crowds and Power as ‘the increase pack.’ It’s no surprise that pamphlets almost have to be amateurish in their design aesthetic — otherwise one might suspect their authors of not being committed enough, of being seduced away from the real issues, of having already too good a grip on establishment tools of power. It’s also no surprise pamphlets tend to suppress proper names or proliferate pseudonyms, proclaim that they are against copyright and other bourgeois property provisions — otherwise they might run the risk of appearing hypocritical. But you don’t have to believe the hype, as the phrase has it, and it’s not certain whether anyone ever really did. Take the analyses of the media theorist Marshall McLuhan, ‘The medium is the message,’ he once famously said, before altering his own message slightly, to: ‘The medium is the massage.’ Media purport to provide you with information — the latest news, for example, or maxims for action — but what they really do, as McLuhan also emphasized, is provide forms of psycho-physiological therapy. Media are essentially remedial; remedial in fact in a number of different senses: not only do they aim to remedy hurts or deficiencies, correct or improve skills; they are literally re-medial, being media about media. ‘The “content” of a medium is always another medium’ proclaims McLuhan. Media don’t ratify a particular viewpoint, but rather render it relative to their own operations; indeed, they drive the proliferation of competing viewpoints in the service of their own dissemination. In other words, media always aim for a mass-age. They effectively produce masses of anonymous persons who, despite not knowing each other, start to act unconsciously in comparable ways precisely because they are all users of the same medium / media. This irrevocable human submission to media creates a kind of ‘Narcissus-Narcosis,’ that is, the druggy, self-loving affects that media users experience, for the most part not suspecting that the limits of the medium are the limits of their world. McLuhan called the new interstellar vistas opened up by the early-modern print revolution the ‘Gutenberg Galaxy’. For McLuhan, the linearity, anonymity, and mass-production of print have consequences for the human sensorium: the suppression of orality-aurality to the benefit of vision, the in-dividuation of persons, and social segmentation. The ‘visual homogenizing of experience’ and functional differentiation of modern social systems is an effect of the dominance of a particular medium, print, a dominance that is now past in the new audio-visual mayhem ushered in by television, etc. In McLuhan’s terms, we are all narcoleptic narcissists, except at those rare moments when the emergence of a new medium shocks us into a momentary recognition that our ways of thinking are programmed by media — before we settle back again into the next generation of self-confirming narcoses.

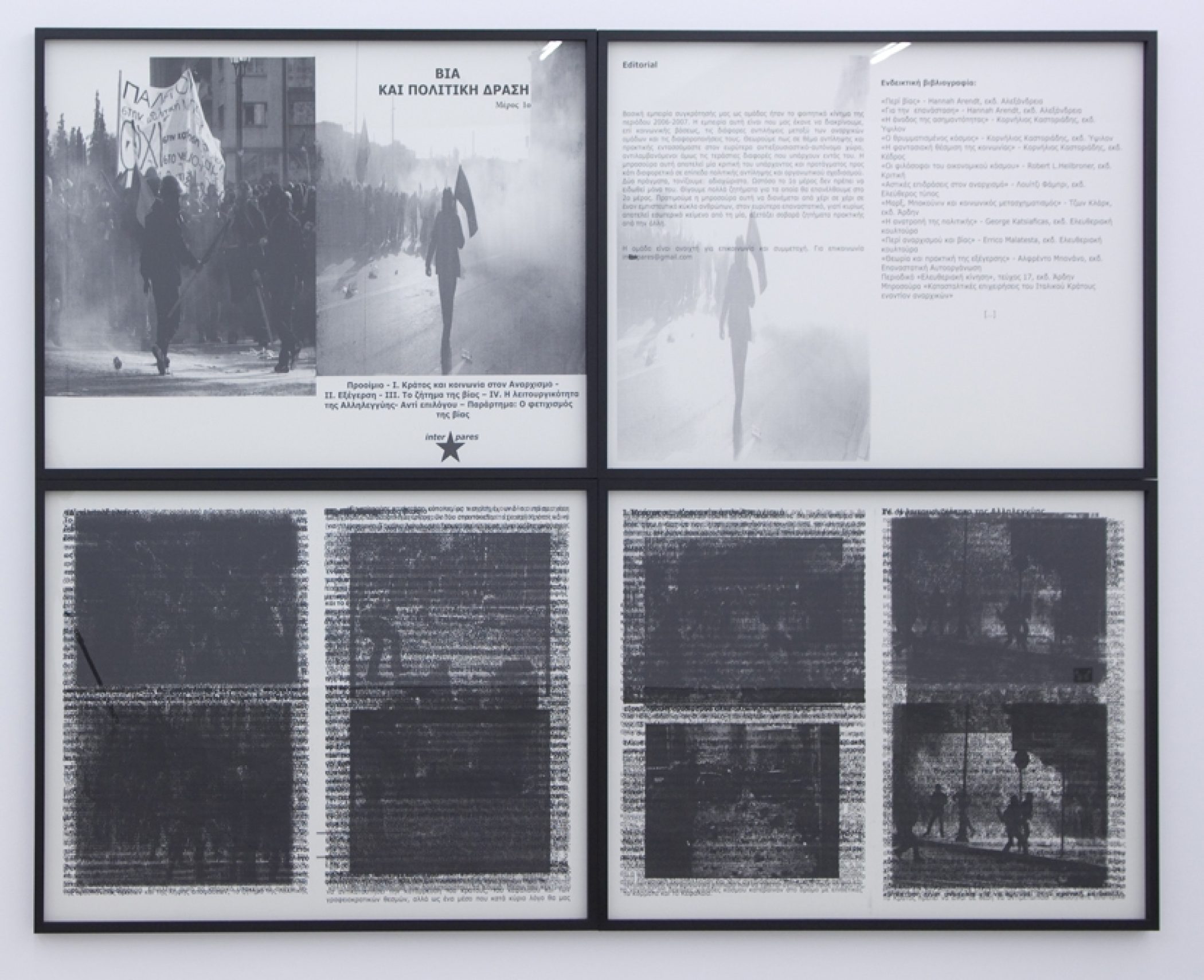

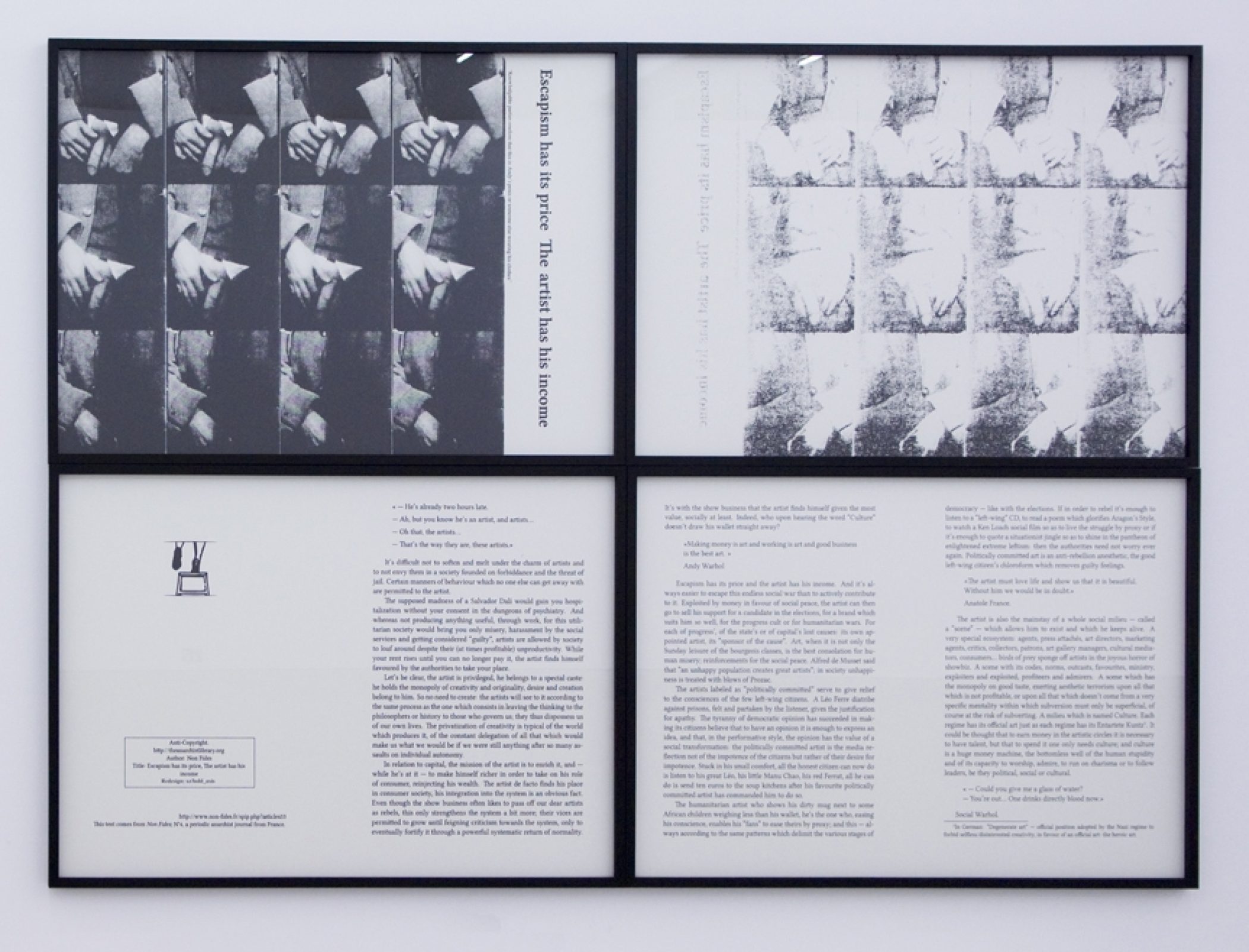

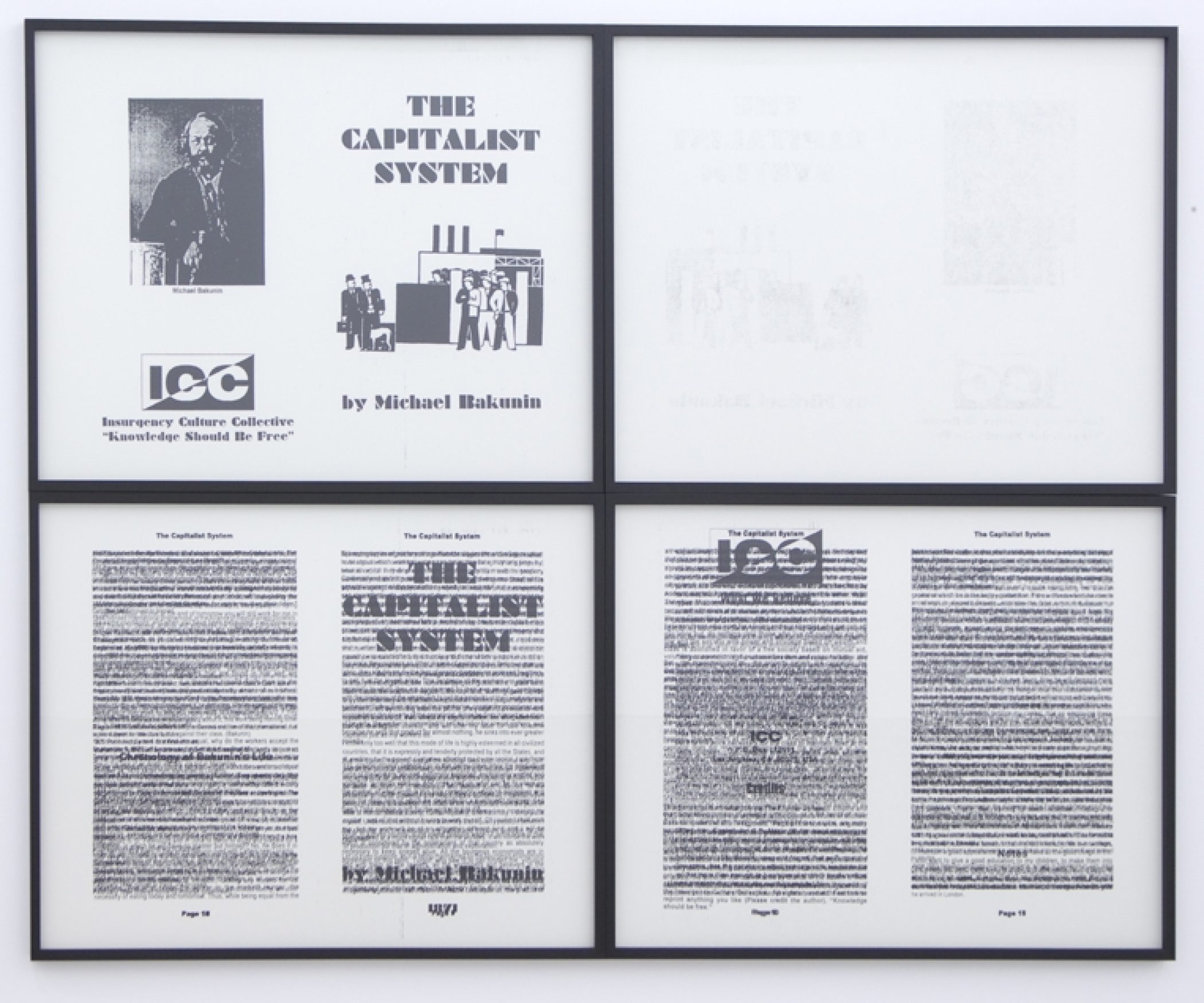

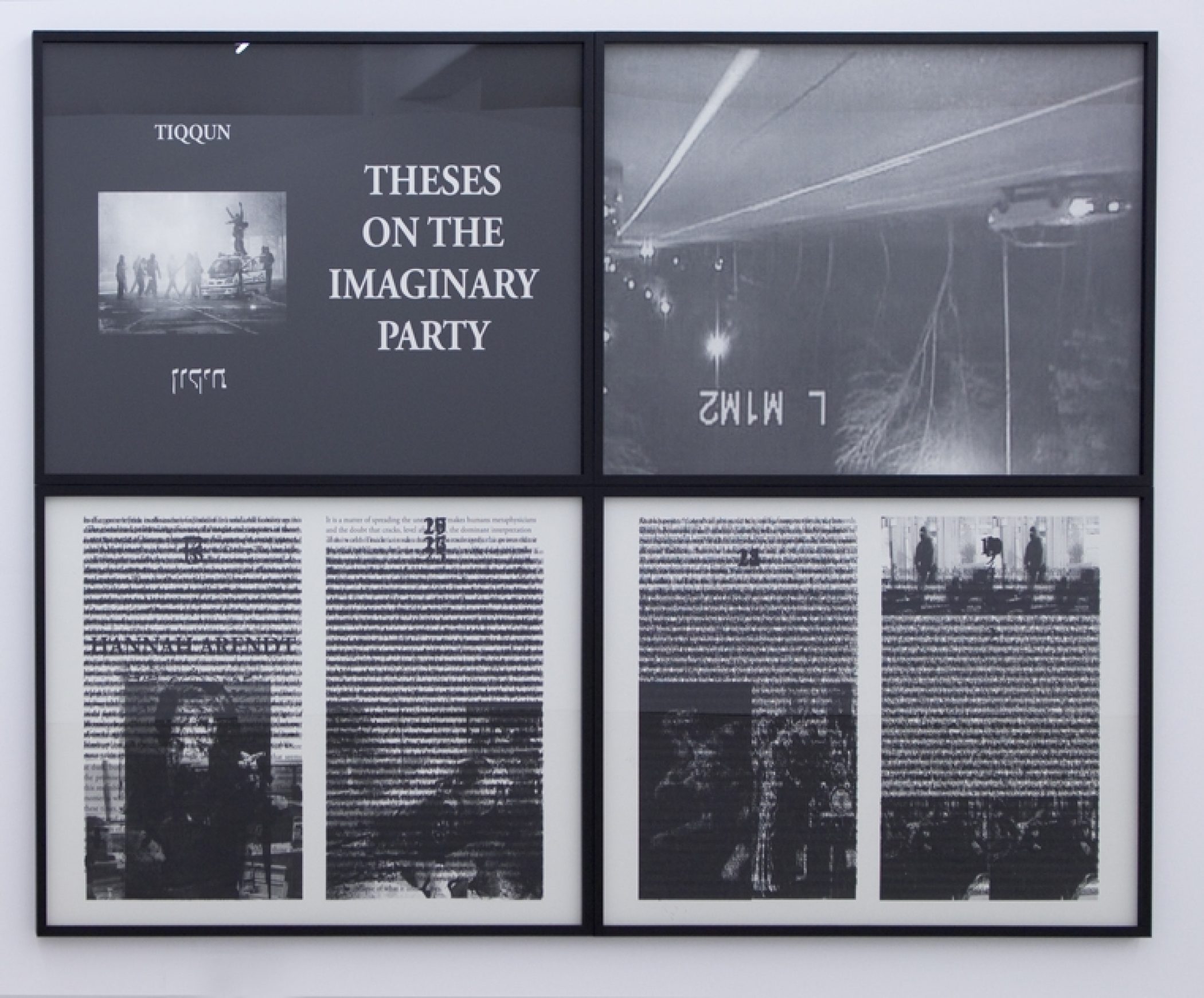

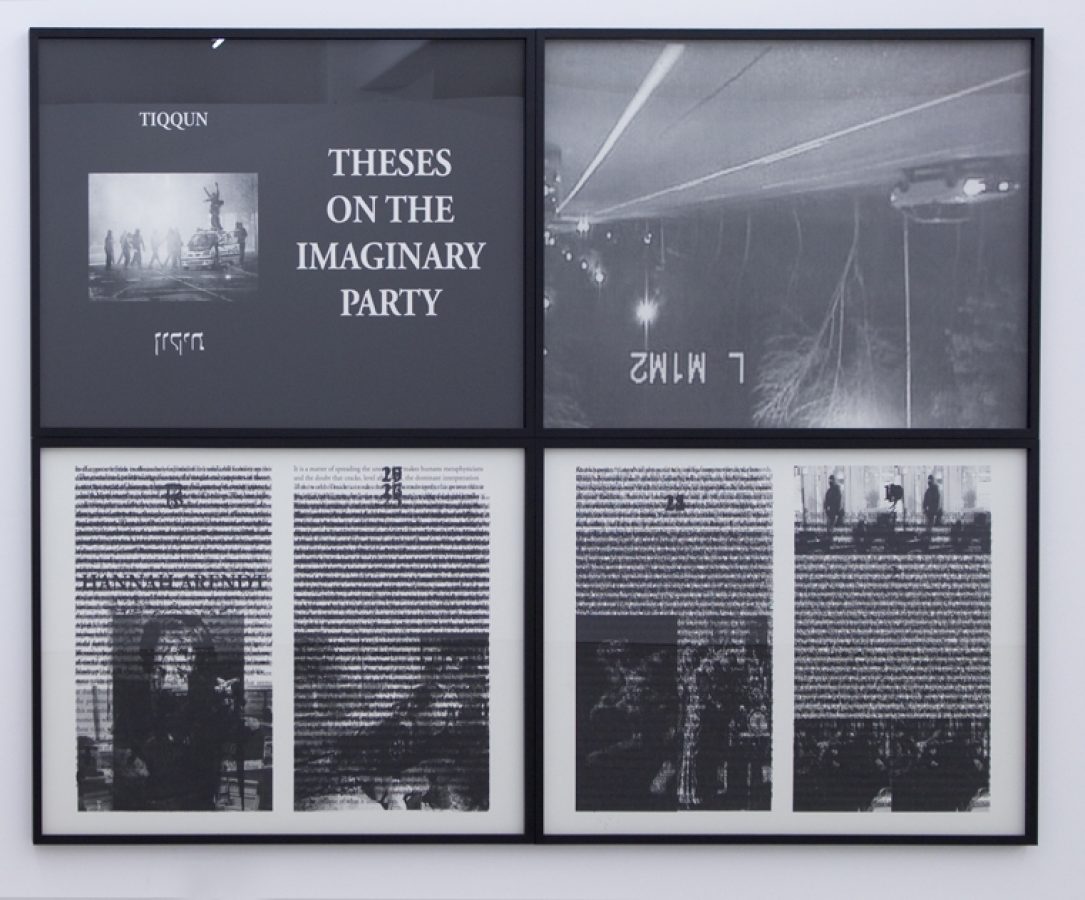

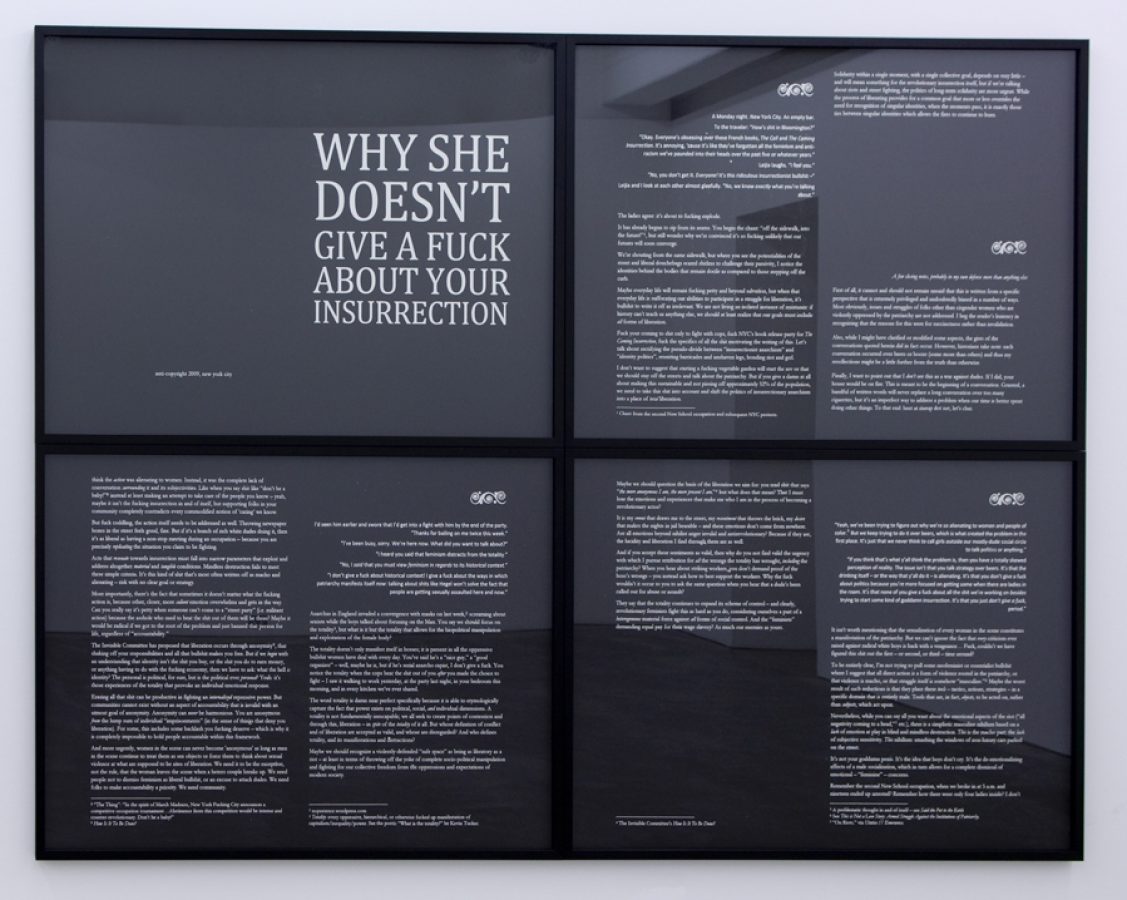

Art is not however a manifestation of media but rather, transforms the media upon which it operates. Art can alert us to our own media-narcoses by means of media themselves. Marco Fusinato selects five pamphlets with titles such as ‘The Capitalist System’ and ‘Theses on the Imaginary Party’ — a form he has long been collecting — and literally blows them up. Fusinato transforms these five pamphlets into five quadripartite works. Every piece of information in the pamphlets has been retained by Fusinato, nothing is lost: the front and back covers, the inside covers, all down-folded pages overprinted, all up-facing pages overprinted. Once handheld, amateurish, multiple, these pages are enlarged, rendered stationary, interior, compacted, until the putative information is overloaded and becomes not so much a galaxy of stars as a fortress of obscurity. The pamphlet once directed against noise becomes an element and tonality of noise itself.

Justin Clemens

Images

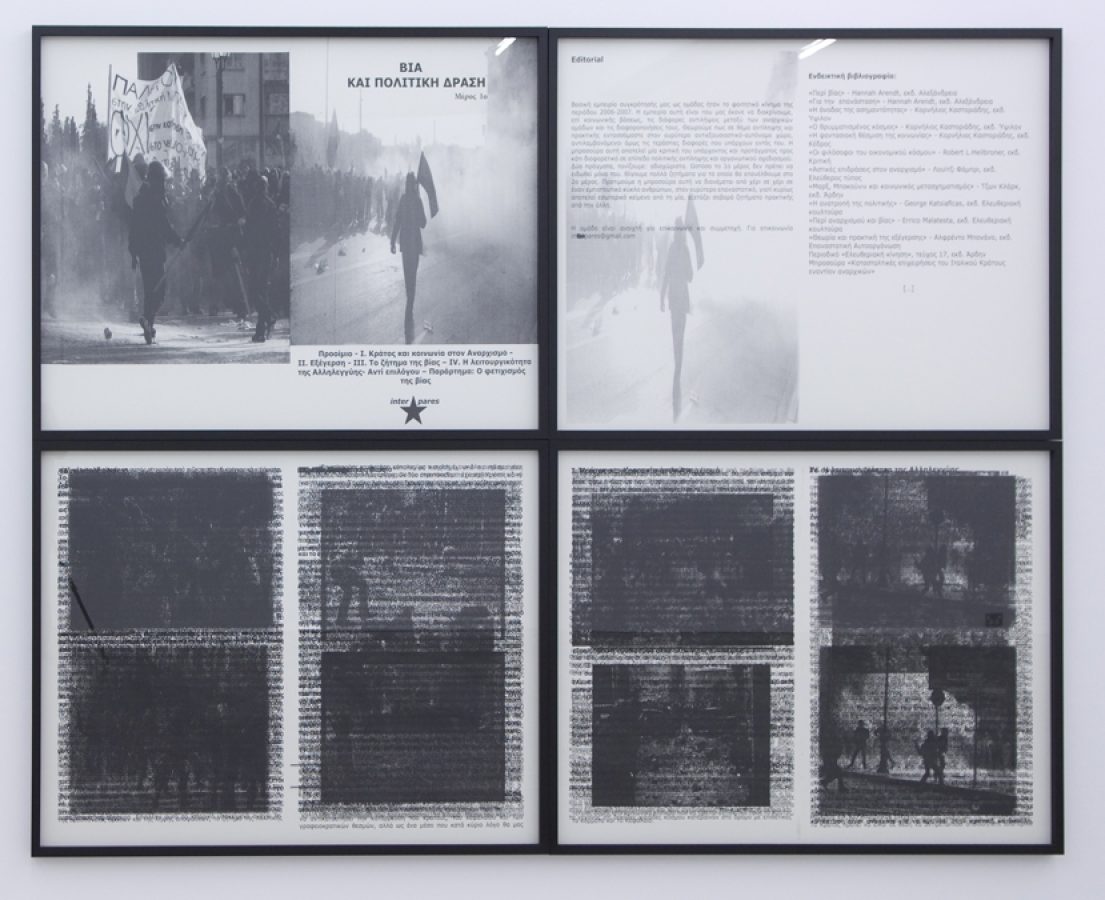

Marco Fusinato

Bia from the series ‘Noise & Capitalism’, 2010

UV and indian ink on Fabriano Artistico 300gsm paper, framed

Four parts, each 116 x 162 cm (232 x 324 cm overall)

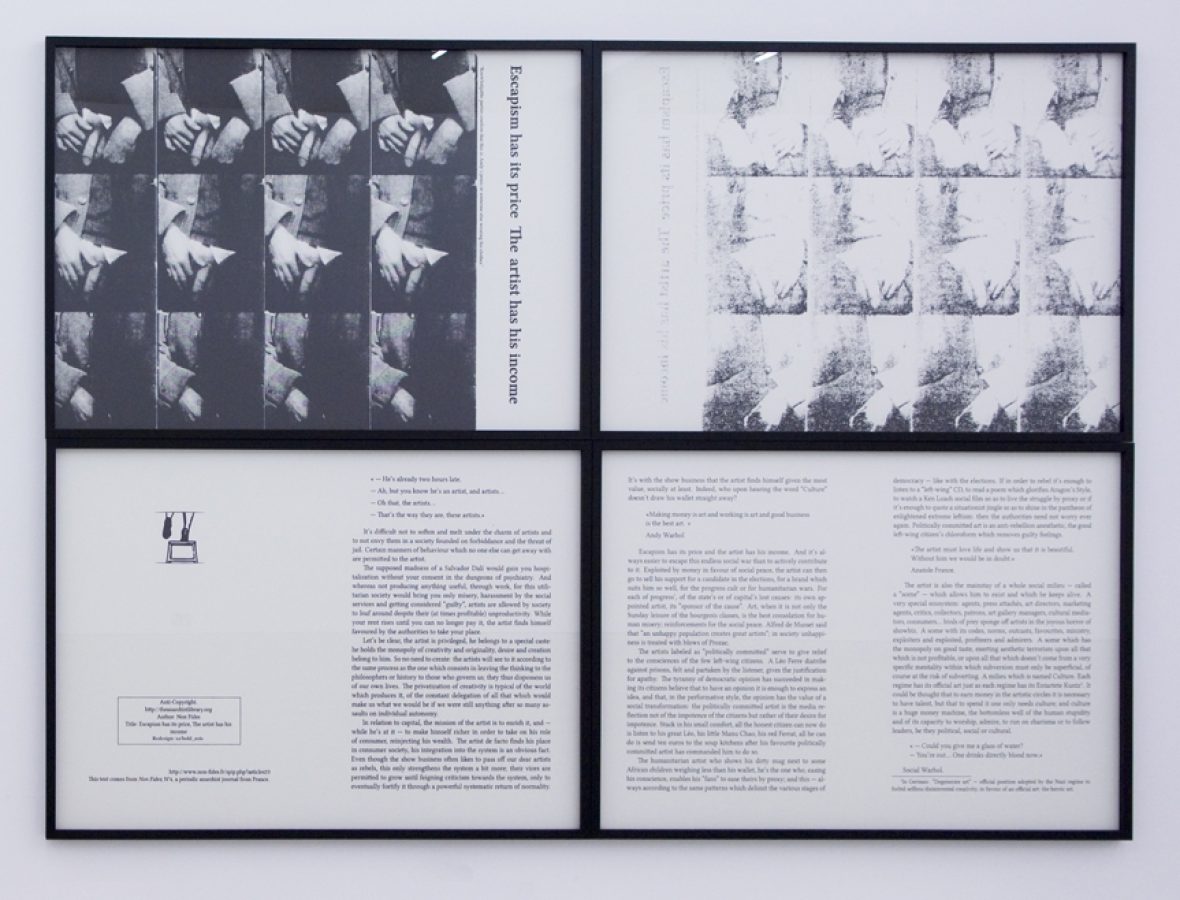

Marco Fusinato

Escapism has its price The artist has his income from the series ‘Noise & Capitalism’, 2010

UV and indian ink on Fabriano Artistico 300gsm paper, framed

232 x 324 cm

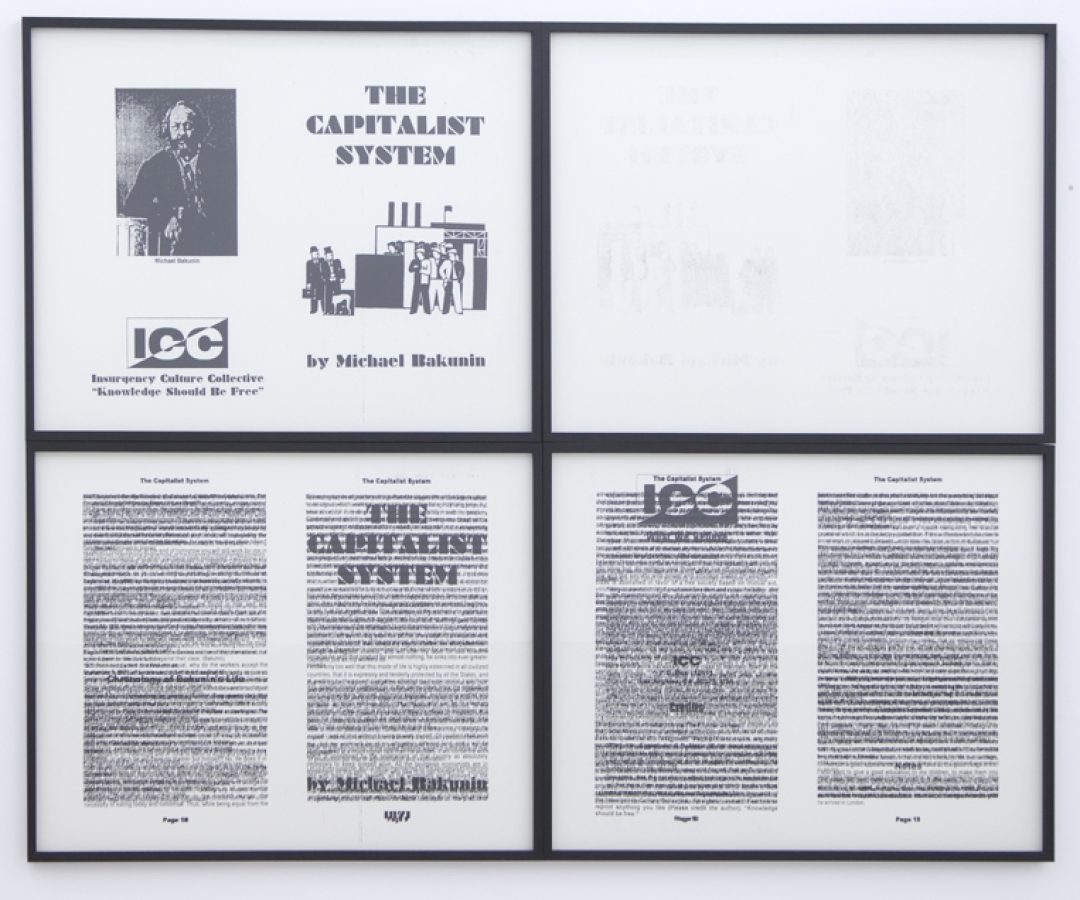

Marco Fusinato

The Capitalist System from the series ‘Noise & Capitalism’, 2010

UV and indian ink on Fabriano Artistico 300gsm paper, framed

Four parts, each 116 x 162 cm (232 x 324 cm overall)

Marco Fusinato

Theses on the Imaginary Party from the series ‘Noise & Capitalism’, 2010

UV and indian ink on Fabriano Artistico 300gsm paper, framed

Four parts, each 116 x 162 cm (232 x 324 cm overall)

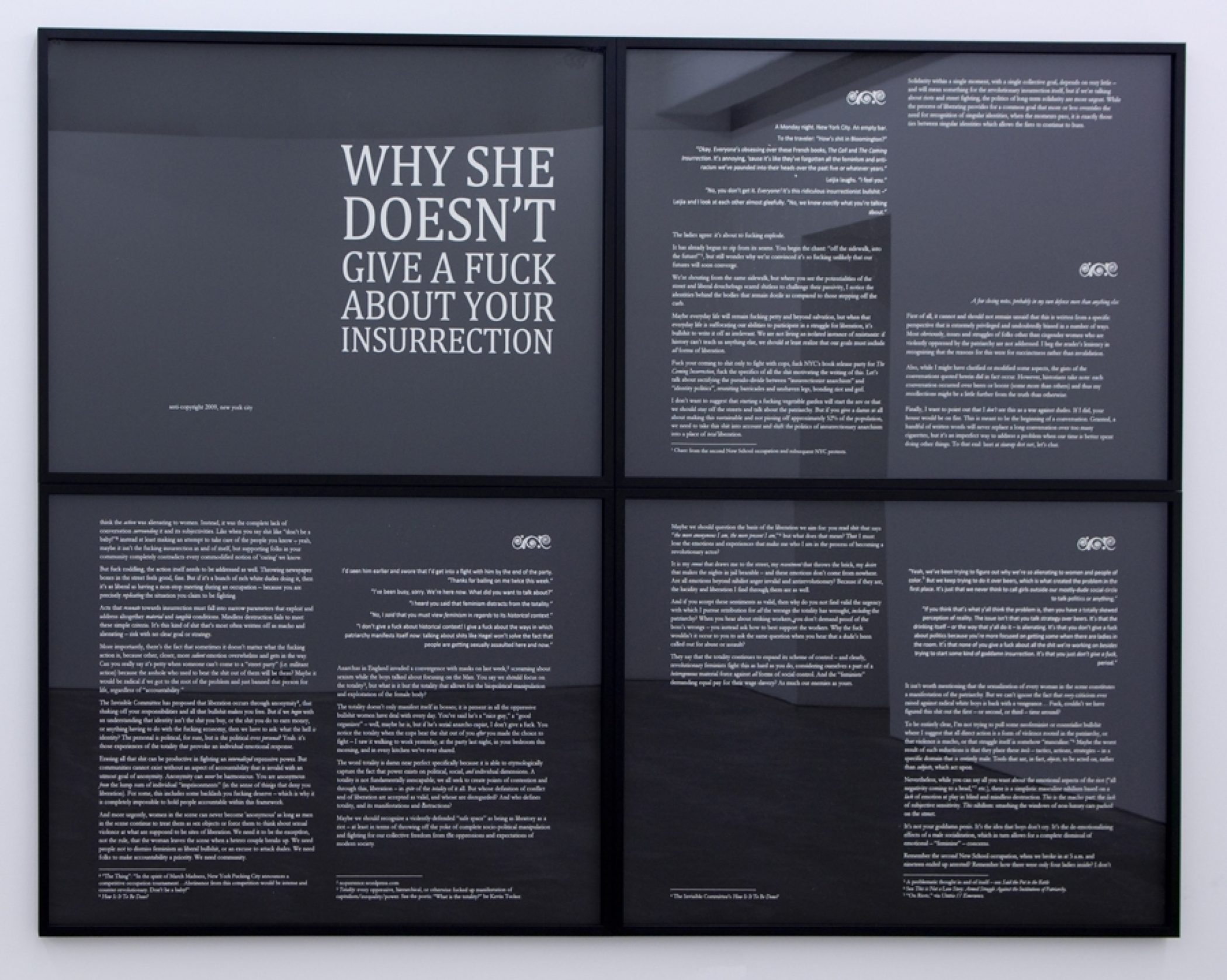

Marco Fusinato

Why she doesn’t give a fuck about your insurrection from the series ‘Noise & Capitalism’, 2010

UV and indian ink on Fabriano Artistico 300gsm paper, framed

Four parts, each 116 x 162 cm (232 x 324 cm overall)