Jan Nelson

Marshland

3rd June – 2nd July 2011

Anna Schwartz Gallery

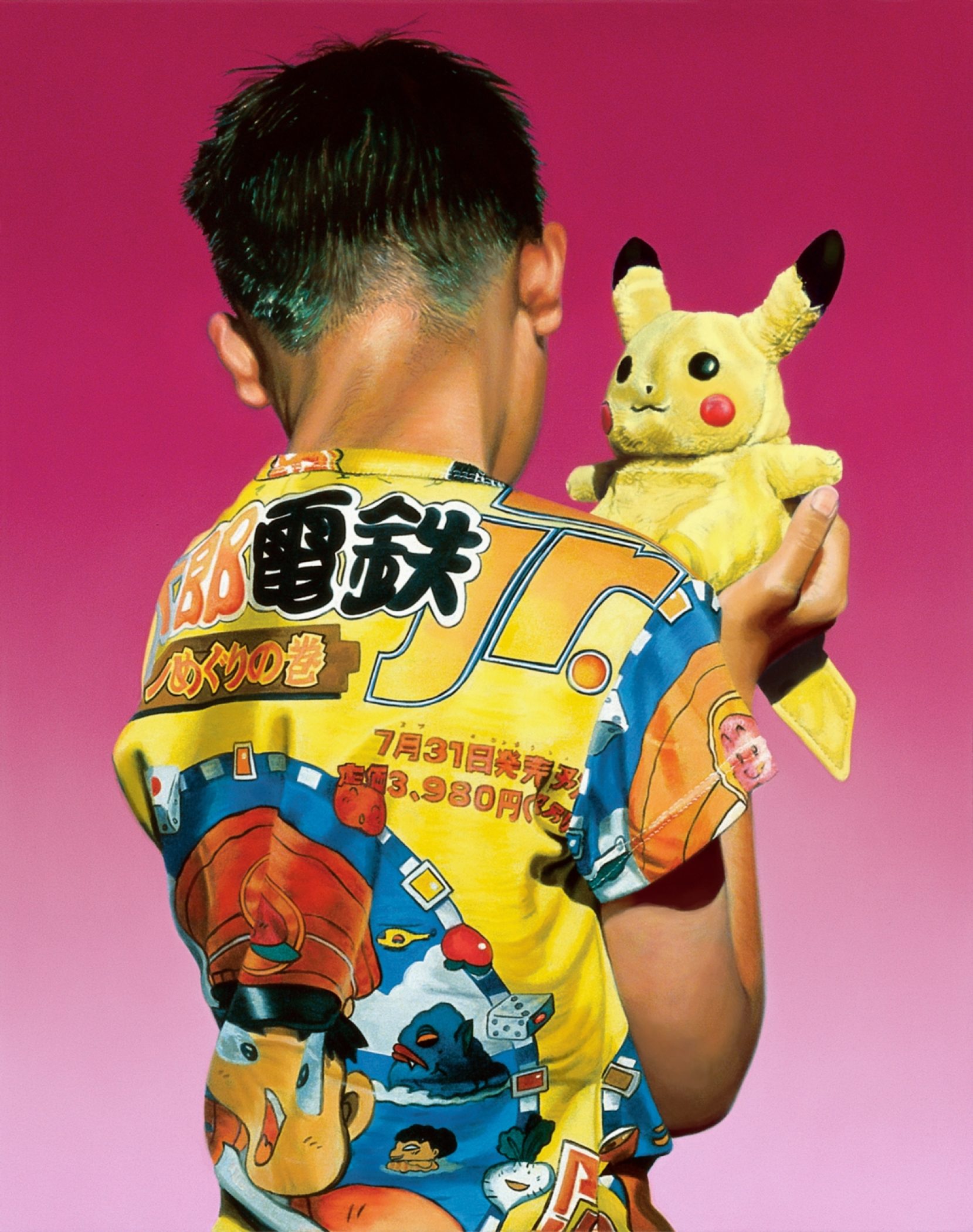

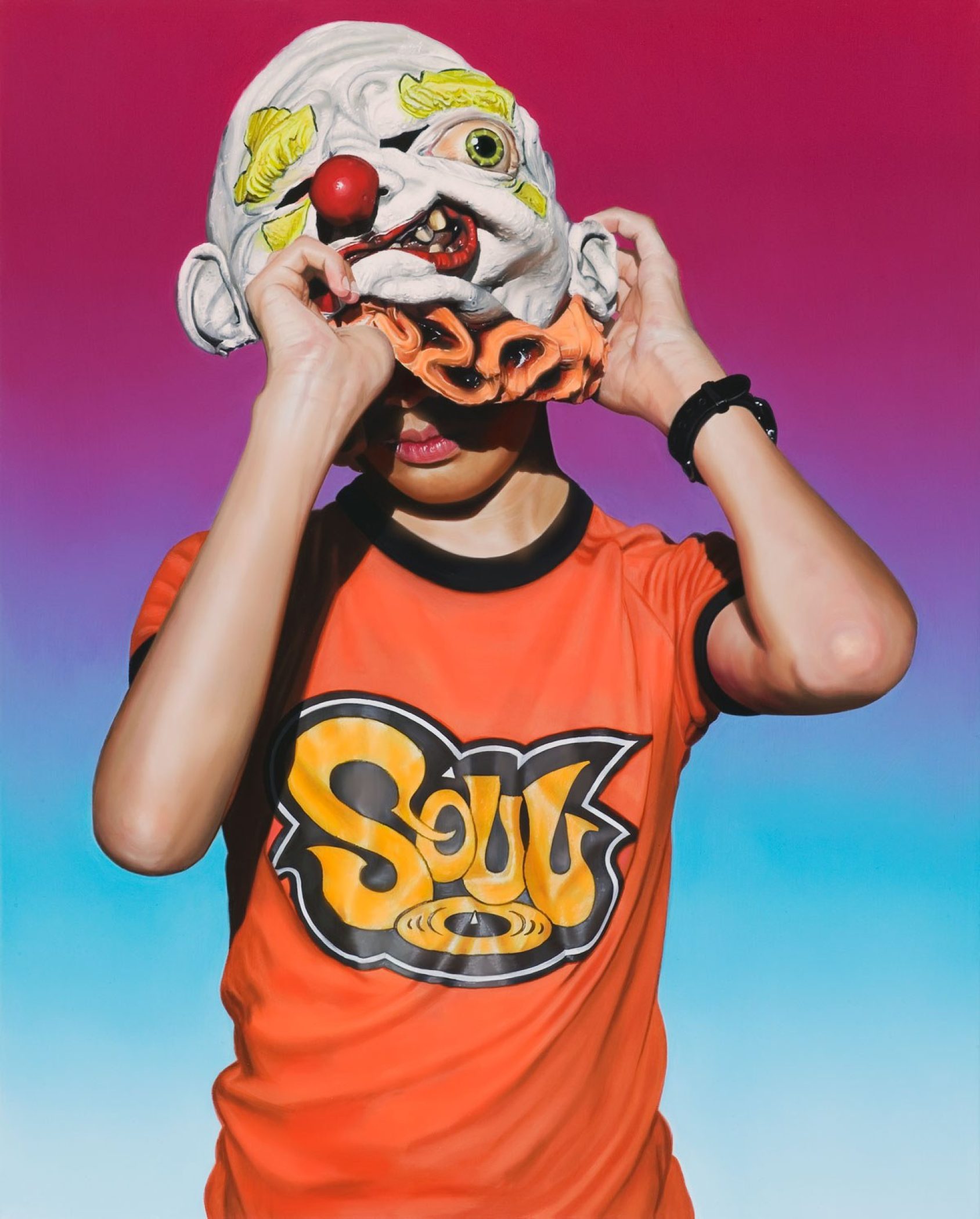

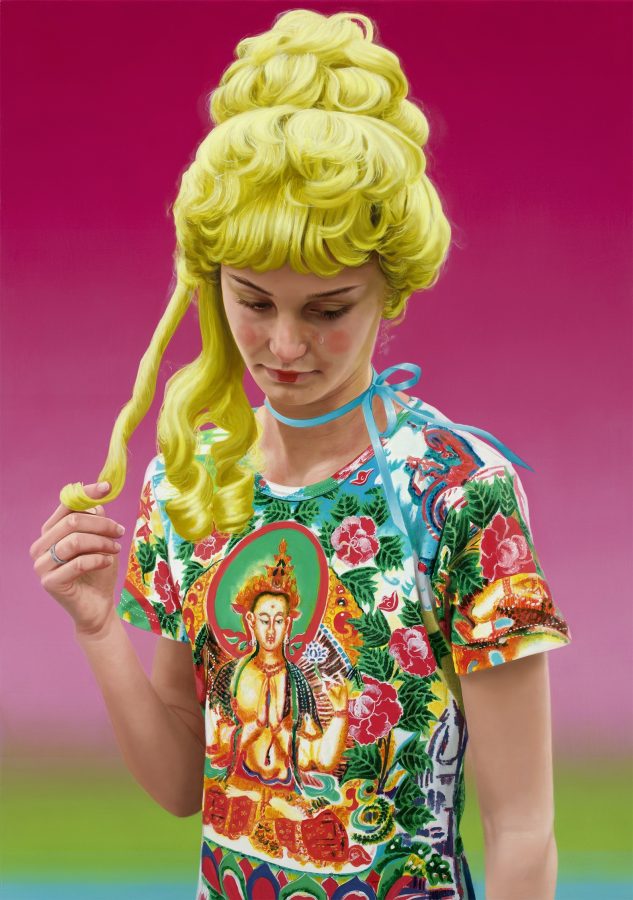

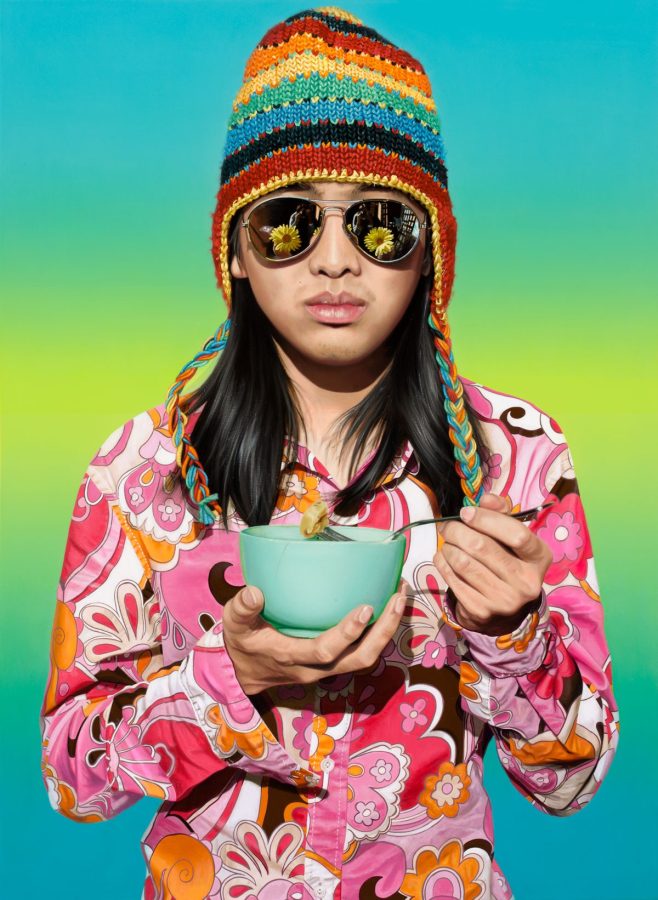

Jan Nelson’s Marshland features new works from the continuing series Walking in Tall Grass. In these hyper-realistic portrait paintings, Nelson depicts adolescence in colourful isolation: individual portraits of young teens who avoid the viewer’s gaze and remain defiantly absorbed in themselves. Lucy’s headphones cancel out the noise of the world, and communication with Gracie is deferred as our empathy is channeled instead through the imploring gaze of her puppy. Nelson’s subjects are named, but by no means do they allow themselves to be identified — these youths wear their layers of mirrored sunglasses, comical masks, hats, and codified clothing as impenetrable defenses.

Drenched in bright, clear light, each figure is starkly defined against a saturated background of abstract graduated colour. This lack of specific context intensifies each subject’s isolation, further refusing us any means of locating and interpreting the individual figures. Instead of a legible landscape, Nelson builds up planes of intense and luminous colour — allowing no escape beyond the picture plane for the subject, nor the viewer’s eye. The dynamism of hue and pattern oscillates within and around the subject, who is frozen in the millisecond of camera exposure.

Positioned at the juncture of painting and photography, Nelson’s works are a constant reminder of the role that time plays in each. However, Nelson refuses to be complicit in the particular conventions of either: these paintings call into doubt the documentary function of photography, whilst also deferring the insight into a sitter’s personality that the portrait genre claims to provide. The repetition of particular subjects who recur in the Walking in Tall Grass series, with alterations to their pose or costume serves to remind us again of the process involved in each painting.

A seamless synthesis of style and subject, Nelson’s paintings emit tension, struggle and ultimately achievement. As well as the apparent conflict between photography and painting, each work displays masterful control of the pigment, where colours appear translucent and layered instead of muddied by their relative proximity. There is a pull between the perceived age of the sitters and the iconography they wear — the aviator sunglasses and paisley prints signify larger and older revolutions than their own. And a tension between these subjects and ourselves, reading but never quite connecting with Nelson’s portraits.

Images

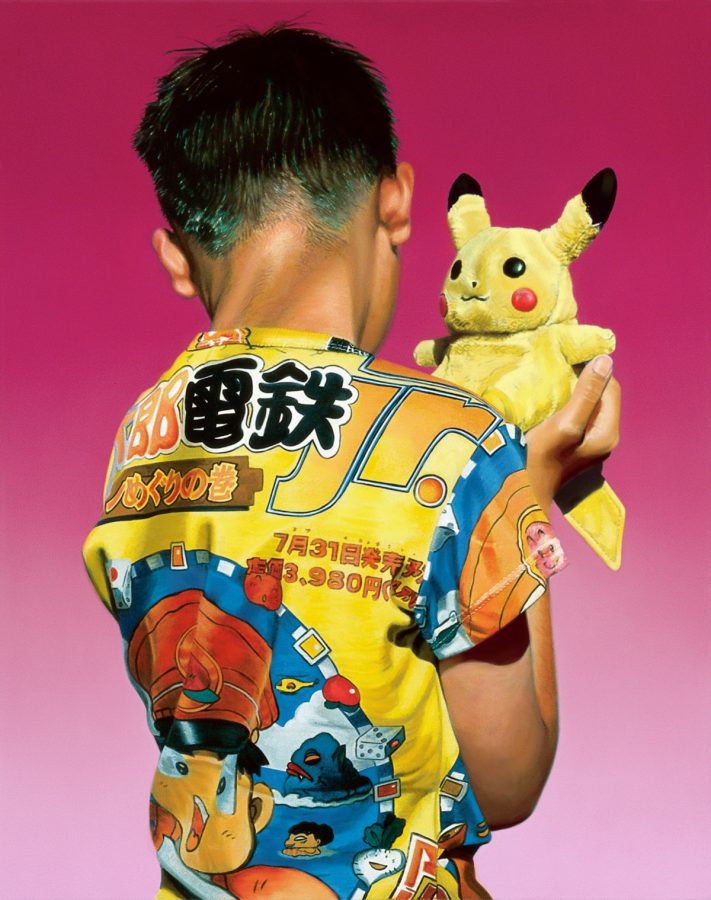

Jan Nelson

Walking in Tall Grass, Betty, 2010

oil and liquin on linen

76 x 53.5 cm

Jan Nelson

Walking in Tall Grass, Iris, 2007

Oil on linen

74.5 x 57 cm

Jan Nelson

Walking in Tall Grass, Gracie 1, 2010

oil on linen

77 x 59 cm

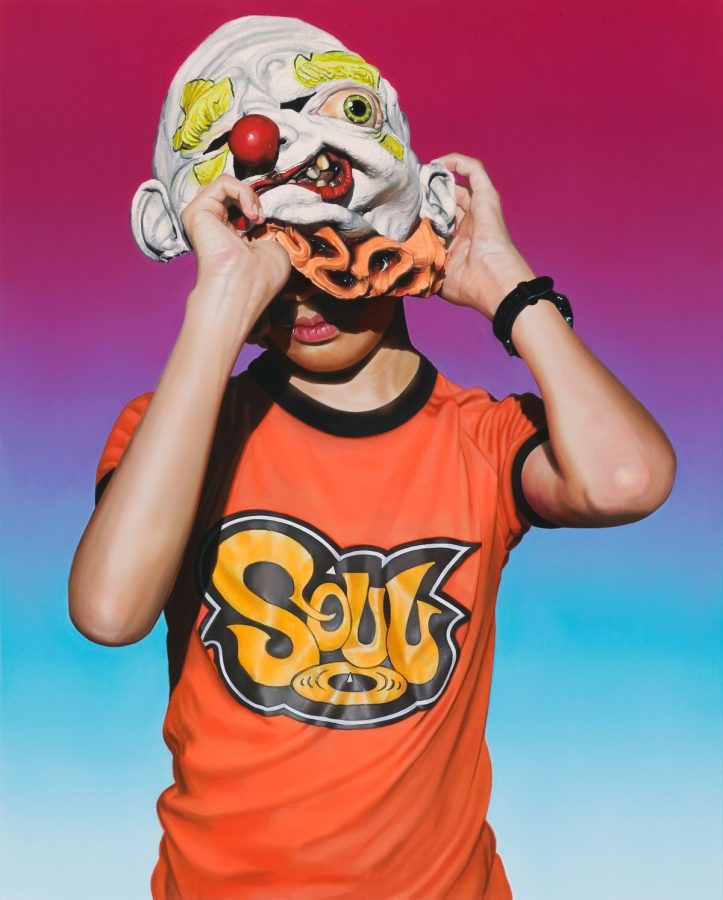

Jan Nelson

Walking in Tall Grass, Carter, 2010

Oil on linen

77 x 60 cm

Jan Nelson

Walking in Tall Grass, Silas 2, 2010

Oil on linen

77 x 54.5 cm

Jan Nelson

Walking in Tall Grass, Tom, 2009

oil on linen

77 x 57.2 cm

Jan Nelson

Walking in Tall Grass, Tim, 2010

Oil on linen

77 x 57.5 cm

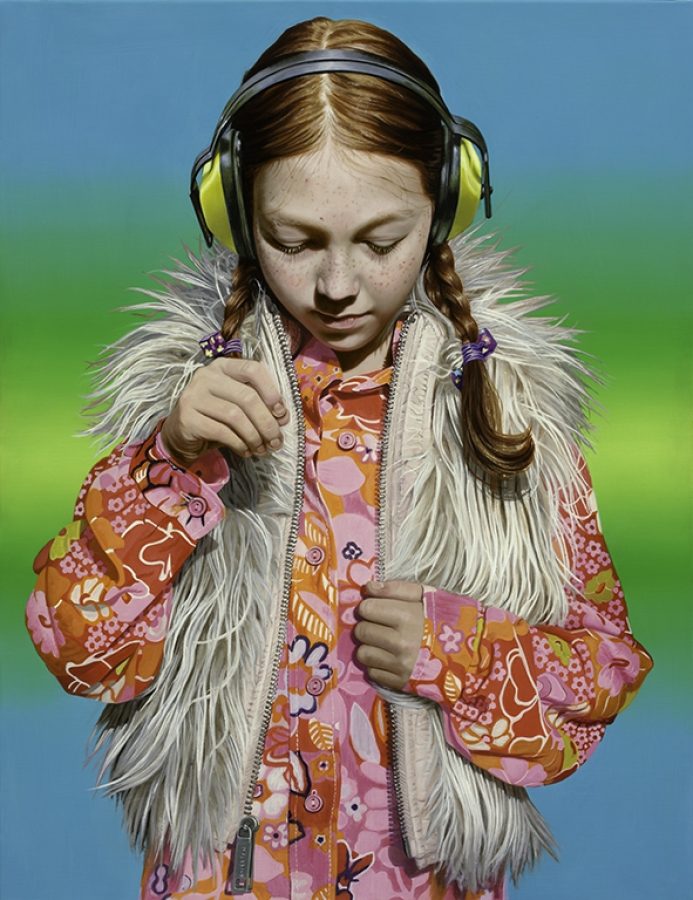

Jan Nelson

Walking in Tall Grass, Lucy 2, 2010

Oil on linen

77.5 x 59.5 cm

Jan Nelson

Walking in Tall Grass, Lauren, 2007

Oil and liquin on linen

79.5 x 63 cm

Jan Nelson

Walking in Tall Grass, Marion, 2011

Oil on linen

77.5 x 59.8 cm

Jan Nelson

Walking in Tall Grass, Victor, 2005

oil on linen

79 x 63.5 cm