Shaun Gladwell

Double Voyage

14th August – 6th September 2008

Anna Schwartz Gallery

Dr Kit Messham-Muir

Equilibrium: Shaun Gladwell’s Double Voyage, 2006

When I was about six years old, my Dad decided it was time I learned to ride a bicycle. He sat me on an old, oversized postman’s bike and pushed me down our street, trying to shout instructions over the sounds of my screams. Though my memory is sketchy, I clearly recall my fear at how wildly unnatural it felt. Then at a certain moment, after hours of gravel rash and tears, everything suddenly clicked into place. I could balance, peddle and steer at the same time. From then on, I rarely thought about balancing again – it just felt right. Probably the only time since then, when I was conscious of balance, was for a brief moment when I cycled at speed across gravel as a teenager. In a second I became aware of lack of balance and was painfully reintroduced to gravel rash. Living necessitates these more or less complex skilled engagements with the world. When we learn to ride a bike, drive, walk, swim or play football, we perform skills that have become ‘naturalised’, as though part of us. A fascination with skilled performance underlies much of Shaun Gladwell’s video works; however, it is the intuitive relationship between performance and an internalised sense of equilibrium that comes to the fore in Double Voyage, 2006.

Performance is an overt theme in Gladwell’s work. Storm Sequence, 2000, while primarily a retake on sublime aesthetics, focuses on the honed skateboarding skills of the artist. Gladwell is both the artist and the performer. Similarly in Kickflipper, 2000, Woolloomooloo Night, 2004, and other works, Gladwell documents skilled performances. In fact, these works are not documentations, as Blair French notes, Gladwell’s works are a kind of ‘study’. The slowing down of motion that characterises Gladwell’s work is an aesthetic exploration of movement. He slows human motion to a point at which at the subtleties of the movements of bodies are cracked open.

Equilibrium is also an ongoing subtext in much of Gladwell’s work. Works such as Pataphysical Man, 2005, Busan Triptych, 2006 and In a Station of the Metro, 2006, are poetic explorations of equilibrium in its everyday sense, literally as balance. His performers move or hold their bodies in a state in which all forces acting on them are equal. However in Double Voyage, 2006, equilibrium functions in more subtle and layered ways, literal, metaphorical and phenomenological.

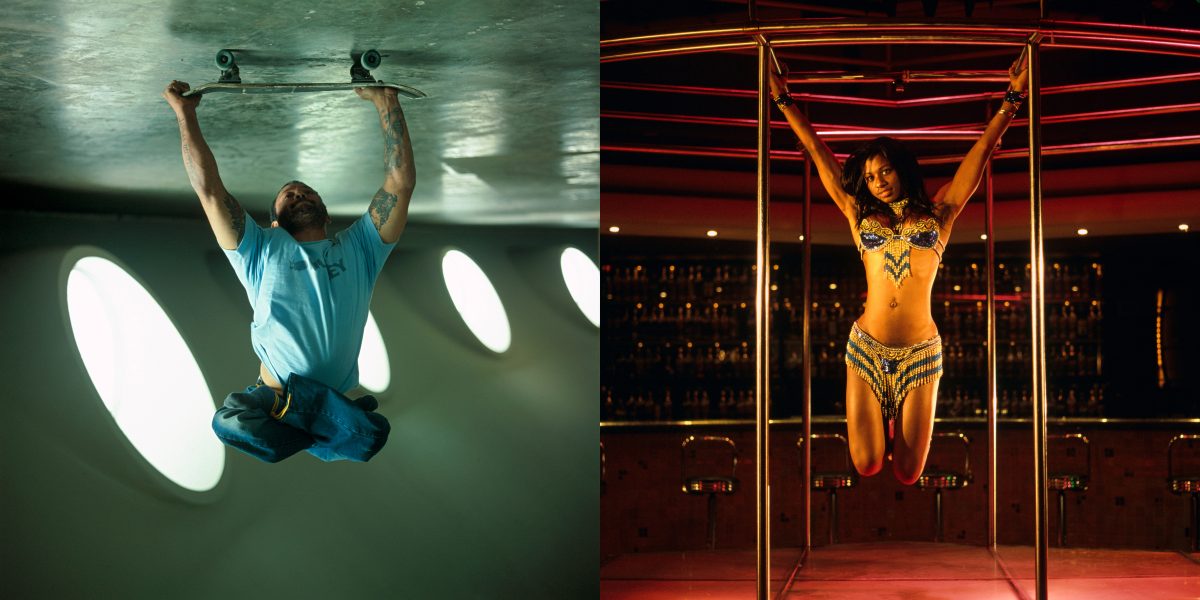

Beneath the literal balancing acts shown, equilibrium functions conceptually as a metaphor. Double Voyage is a double portrait, and its portrayals oscillate through the tension of intersecting dualities. The two performers in Double Voyage become mid points in a nexus of binaries – able-bodied/disabled, male/female, upright/inverted, left/right, subcultural/canonical, erotic/athletic. Importantly, in Double Voyage these binaries are held in balance – these dualities are unresolved and ambiguous. They are played off against each other, as equal forces holding subjectivities in equilibrium, in a state of being and becoming.

The particular bodies in Double Voyage bring another layer to the work. In terms of mainstream normalisations, these could be seen as problematised bodies – the skateboarder, Og D’Souza, cannot use his legs, something we might think as a prerequisite for a skateboarder. The apparent disjunction between the possible and not, draws our attention more acutely to his performance. The dancer, Grace O’Hara, is transsexual, and Judith Butler’s argument that gender is a performance is perfectly played out. Both performers defy, even exploit, their ‘natural’ condition, self-willed into being in defiance of their capacities. And they enact a performative ‘passing’ – they are both unquestionably that which they perform.

Through these two performances, Double Voyage also explores equilibrium in a deeper and more complex phenomenological sense, that is, to do with how we experience the world. Gladwell studies these performances as an athlete would consider his/her own performance – not as display, but as a body engaging its’ world with a particular skill.

The phenomenologist philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty uses the word ‘equilibrium’ in a particular sense, as something internally felt in performance of a physical skill. Learning a physical skill (whether skateboarding, dancing, driving a car or flying a plane) is a fundamentally experiential process. And our experience of the relationship of our bodies to the skill evolves qualitatively. The building blocks at first do not seem natural, and the formative process is one of internalising and habituating the unnatural. A novice coming to a new skill is given consciously-learned rules, which are about reading signs and responding in defined ways. When we learn to drive, for instance, we learn that a certain pitch of the engine’s sound means a change of gears is needed. As skill develops, Hubert Dreyfus argues, “the performer’s theory of the skill, as represented by rules and principles will gradually be replaced by situational discriminations accompanied by associated responses. Proficiency seems to develop if, and only if, experience is assimilated in this atheoretical way and intuitive behaviour replaces reasoned responses.” So, through innumerable and repeated experiences, literally trial and error, these rule-based processes become compressed into our being. We are no longer conscious of specific actions as the basic rules become adapted, slowly habituated and naturalised into our being, ingrained in what Merleau-Ponty calls our ‘carnal formulae’.

As skill reaches the level of expertise, we are not aware of specific decisions, our response is not solicited by conscious thought but by a more generalised desire to maintain a feeling of integrity. As Merleau-Ponty claims, “whether a system of motor or perceptual power, our body is not an object for an ‘I think’, it is a grouping of live-through meanings which moves towards its equilibrium.” We experience our body as moving according with maintaining or deviating from its internal feeling of equilibrium. When this sense of equilibrium is sustained, we feel a pleasant sense of being absorbed and at one with the task; when it is disturbed, the character of the learned skill is momentarily laid bare. The underlying maintenance of equilibrium becomes the primary motivation of a habituated action, rather than the more obvious goal. The process seems automatic, even physiologically autonomic.

In Portuguese, the word for this feeling of maintaining equilibrium is ginga, pronounced ‘jinga’. The notion of ginga is often used in relation to the execution of skill in Brazilian football, but is actually borrowed from capoeira, the Brazilian martial art and dance form. Capoeira, is based on a triangular step pattern, a ‘centred’ base from which other body movements are made. It is a movement of continuously flowing equilibrium, balancing from foot to foot, as seen in Gladwell’s Woolloomooloo Night, 2004. Similarly, in Double Voyage we see the outward bodily expression of an internal sense of equilibrium. In creating a contemplative space and time, Double Voyage breaks open the equilibrium, the flow of the ginga, and renders this internal feeling momentarily visible.

Images

Shaun Gladwell

Double Voyage, 2009

two-channel video installation

24 minutes 5 seconds

installation view, Anna Schwartz Gallery

Shaun Gladwell

Double Voyage, 2006

two-channel video installation

24 minutes 5 seconds

Performers: Og de Souza, Gracie O’Hara

Cinematographer: Gotaro Uematsu